Whitewashing Lee’s Army: Gettysburg and the Erasure of Black History

Director Ron Maxwell’s Gettysburg (1993), one of my all-time favorite films, is the definitive cinematic depiction of the famous battle. The movie chronicles the epic three-day struggle between the Union Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia for the fate of the nation. Based on Michael Shaara’s novel The Killer Angels (1974), the film features an epic soundtrack and top-notch performances from its cast.

The more I study the battle, however, the more apparent the film’s historical inaccuracies become. Race is one area in which Gettysburg falls short. Although the movie’s 271-minute runtime includes multiple discussions about slavery, it features only a single African American character—a runaway slave whose sole purpose is to spark a conversation between Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and (the fictional) Sergeant ‘Buster’ Kilrain.

Despite the historical reality that thousands of black slaves accompanied the Confederate Army into Pennsylvania, the force shown in Gettysburg is monochromatic. The film devotes plenty of screen time to Confederate encampments and units on the march. Where are all the black Southerners who served in numerous non-combat roles?

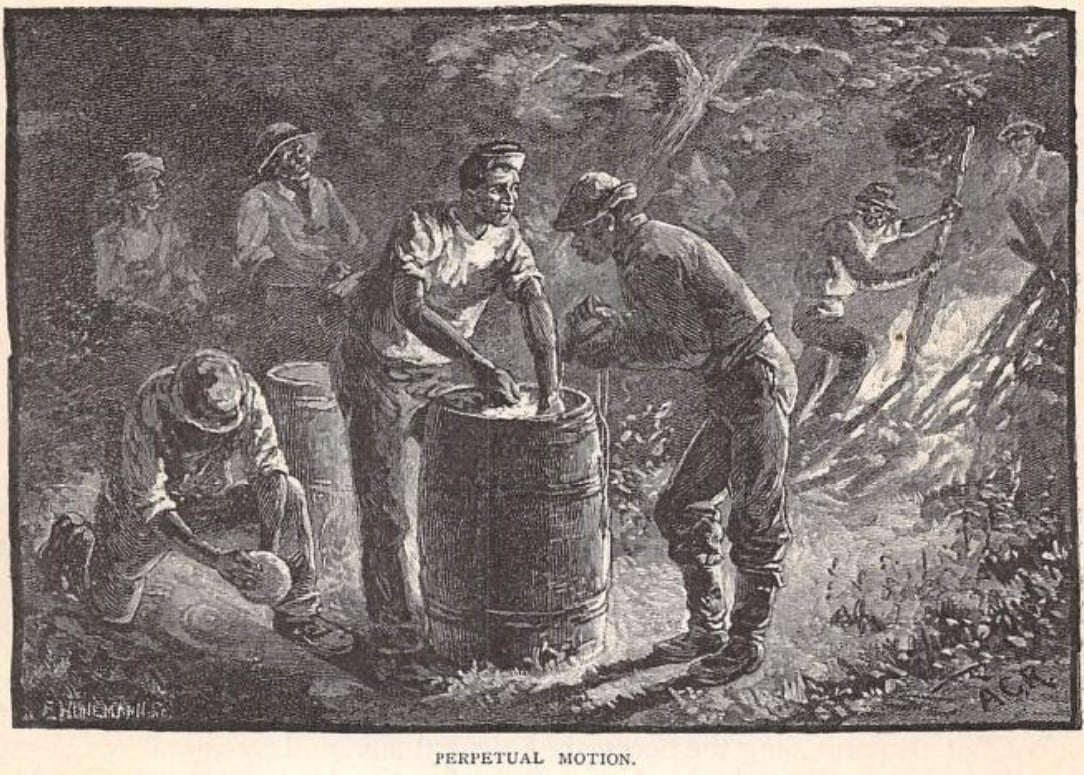

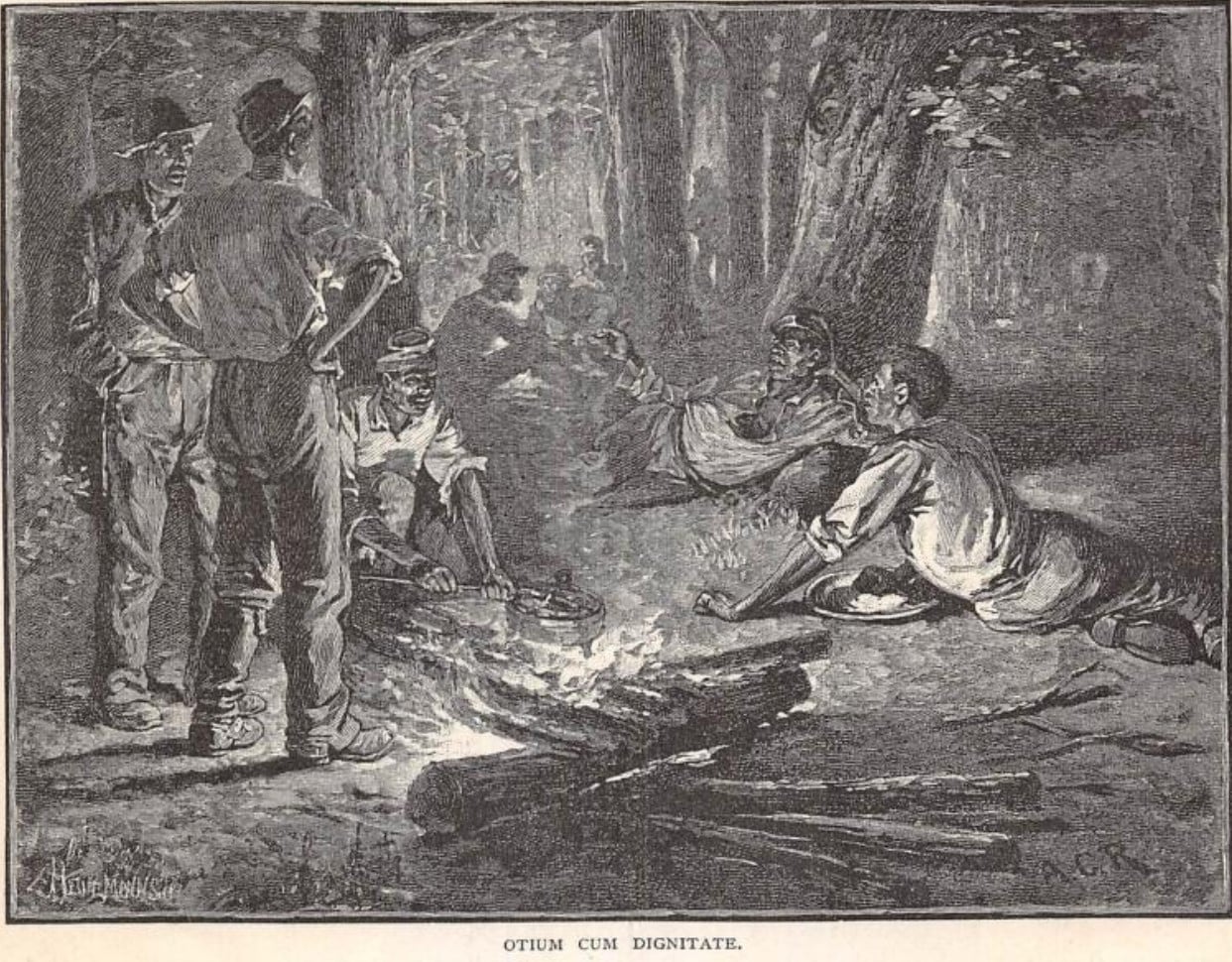

In the Confederate army, black Southerners (mostly enslaved, but some freemen) performed tasks such as cooking, washing, foraging, tending horses, blacksmithing, and digging graves. They served as teamsters, musicians, and even hospital orderlies.[1] If the filmmakers were genuinely striving for historical accuracy, how could they overlook such an obvious fact?

We know from contemporary sources that black Southerners played an active part in the Army of Northern Virginia. For instance, Major Johann August Heinrich Heros von Borcke, a Prussian cavalry officer on Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s staff, recalled Stuart being alerted to the fighting that began the battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863, at the opening of the Gettysburg campaign:

“Stuart was now promptly awakened, the entire headquarters alerted, the nearby horses saddled by the Negro servants, and everything placed in readiness for the impending engagement.”[2]

Likewise, Capt. Justus Scheibert, a Prussian military attaché, observed:

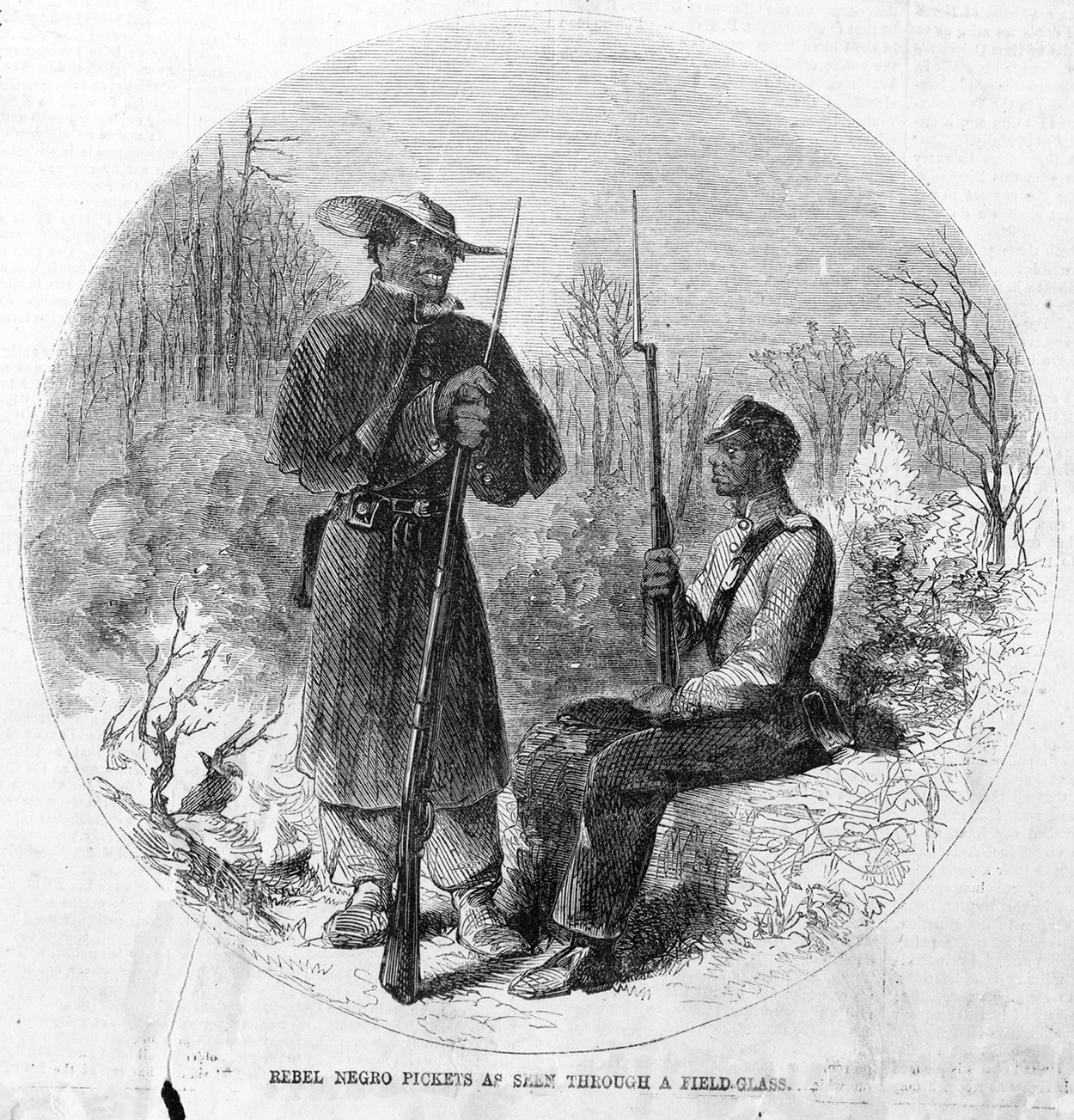

“Here I must remark that the southern cavalry (also the artillery and staff), as soon as they arrived at the camp, immediately unsaddled the horses and either sent them to the fenced pasture or assigned some Negroes to watch over them. The officers’ servants, some wagon drivers, and supply-train soldiers were in fact Negroes, while not a single Negro bore weapons at that time.”[3]

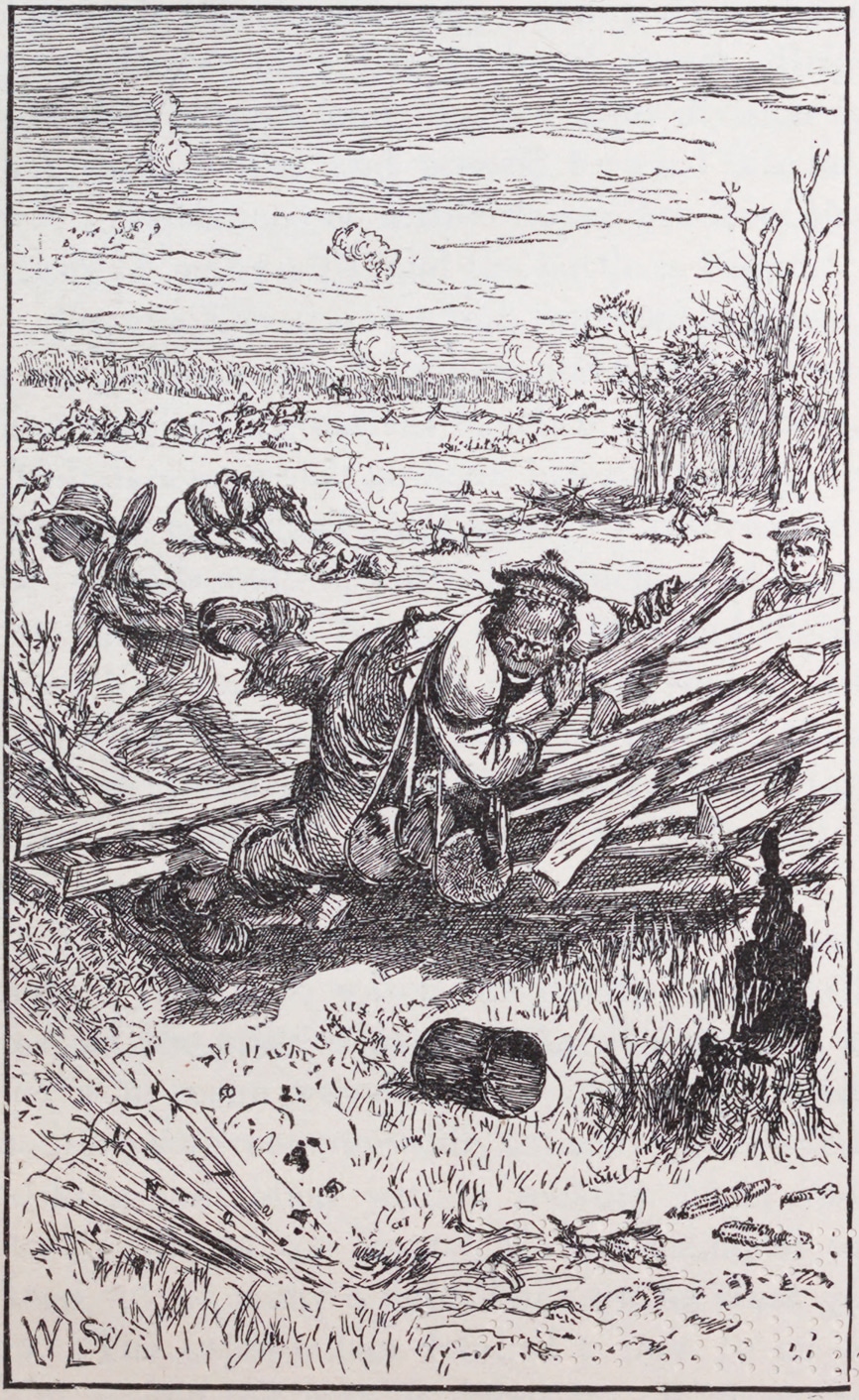

While they did not bear arms on the battlefield, that does not mean they never handled weapons. On July 6, 1863, as the Army of Northern Virginia retreated from Gettysburg, British observer Lt. Col. Arthur Fremantle (portrayed by James Lancaster in the film) “saw a most laughable spectacle”:

“a negro dressed in full Yankee uniform, with a rifle at full cock, leading along a barefooted white man, with whom he had evidently changed clothes. General Longstreet stopped the pair, and asked the black man what it meant. He replied, ‘The two soldiers in charge of this here Yank have got drunk, so for fear he should escape I have took care of him, and brought him through that little town.’ The consequential manner of the negro, and the supreme contempt with which he spoke to his prisoner, were most amusing.”[4]

Fremantle did not say what became of the pair, but the sight of an armed slave passing a Confederate corps commander and his staff evidently was not alarming. Others, like Lewis H. Steiner, an inspector for the U.S. Sanitary Commission, observed slaves carrying weapons while on the march.

During Lee’s 1862 invasion of Maryland, Steiner kept a diary documenting the Confederate occupation of Frederick, Maryland. In his forty-page report, he estimated the strength of Lee’s army and observed the following:

“Over 3,000 negroes must be included in this number. These were clad in all kinds of uniforms, not only in cast-off or captured United States uniforms, but in coats with Southern buttons, State buttons, etc. These were shabby, but not shabbier or seedier than those worn by white men in the rebel ranks. Most of the negroes had arms, rifles, muskets, sabres, bowie-knives, dirks, etc. They were supplied, in many instances, with knapsacks, haversacks, canteens, etc., and were manifestly an integral portion of the Southern Confederacy Army. They were seen riding on horses and mules, driving wagons, riding on caissons, in ambulances, with the staff of Generals, and promiscuously mixed up with all the rebel horde.”[5]

Later, he added, “The only real music in their column to-day was from a bugle blown by a negro. Drummers and fifers of the same color abounded in their ranks.”[6]

Just how many black Southerners (enslaved or otherwise) accompanied the Army of Northern Virginia is difficult to say. They were not considered soldiers and did not appear on official muster rolls, so traditional troop estimates reflect only white men formally serving in the Confederate army. Historian Kevin M. Levin has estimated that Lee’s army brought as many as 10,000 slaves, sometimes called “body servants,” on its 1863 invasion of Pennsylvania.[7]

As McLaws’ Division marched north in June 1863, Fremantle noted, “In rear of each regiment were from twenty to thirty negro slaves, and a certain number of unarmed men carrying stretchers and wearing in their hats the red badges of the ambulance corps.”[8]

During the Gettysburg campaign, Semmes’ and Barksdale’s Brigades each consisted of four regiments, which means between 80 and 120 slaves accompanied each brigade (if Freemantle’s observation was accurate). For Barksdale’s Brigade, that’s roughly a ratio of 1:20 or 1:13. In Semmes’ Brigade, the ratio was more like 1:17 or 1:11.

Historian Allen C. Guelzo estimated that Lee’s army included anywhere from 10,000 to 30,000 slaves prior to the Gettysburg Campaign.[9] Guelzo’s highest figure came from Lt. Thomas Caffey, an Englishman serving in the Army of Northern Virginia who published an anonymous and often error-filled account of his service aimed at persuading overseas readers of the righteousness of the Southern cause. The work devotes an entire chapter to Southern slavery, with particular attention to slaves serving in the Confederate army. Caffey quoted a soldier as saying:

“In our whole army there must be at least thirty thousand colored servants who do nothing but cook and wash. . . They are roaming in and out of the lines at all times, tramping over every acre of country daily, and I have not heard of more than six instances of runaways in our whole brigade, which has a cooking and washing corps of negroes at least one hundred and fifty strong!”[10]

Thirty thousand is undoubtedly exaggerated. Lee had enough problems feeding his own men, let alone an entire corps of camp followers. If Caffey’s claim of 150 slaves per brigade is taken as representative, it suggests a figure only slightly higher than Fremantle’s.

Given the best information we have available, it’s not unreasonable to conclude at least 4,500 to 5,000 slaves accompanied the 75,000-man Army of Northern Virginia into Pennsylvania in June 1863. They even rounded up several hundred free blacks and escaped slaves in Maryland and Pennsylvania, so these must be added to the total.[11]

Depicting the Army of Northern Virginia as mono-racial is not merely inaccurate; it deliberately glosses over the extent to which slavery, and black Southerners more broadly, shaped the Confederacy. Black slaves were a constant presence in Confederate camps, cooking meals, tending horses, and performing a wide range of labor. The all-white army portrayed in films like Gettysburg would have been unrecognizable to actual Southern veterans of the Civil War.

[1] Colin Edward Woodward, Marching Masters: Slavery, Race, and the Confederate Army During the Civil War (Richmond: University of Virginia Press, 2014), 82-83; Allen C. Redwood, “The Cook of the Confederate Army,” Scribners Monthly 18 (May-Oct. 1879): 560-68.

[2] Heros von Borcke and Justus Scheibert, Die grosse Reiterschlacht bei Brandy Station 9 Juni 1863, trans. M.A. Kleen (Berlin: Paul Kittel, 1893), 79-80.

[3] Justus Scheibert, Sieben Monate in den Rebellen-Staaten während des nordamerikanischen krieges 1863, trans. M.A. Kleen (Stettin: Th. von der Nahmer, 1868), 100.

[4] Arthur Lyon Fremantle, Three Months in the Southern States: April-June, 1863 (Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1863), 288.

[5] Lewis H. Steiner, Report of Lewis H. Steiner, inspector of the Sanitary Commission, Containing a Diary Kept During the Rebel Occupation of Frederick, MD (New York: Anson D. F. Randolph, 1862), 19-20.

[6] Steiner, Report of Lewis H. Steiner, 21.

[7] Kevin M. Levin, Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 48.

[8] Fremantle, Three Months in the Southern States, 238.

[9] Allen C. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion (New York: Vintage Books, 2014), 161.

[10] [Thomas Caffey], Battle-Fields of the South, from Bull Run to Fredericksburg, Vol. II (London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1863), 58-59.

[11] Robert J. Wynstra, At the Forefront of Lee’s Invasion: Retribution, Plunder, and Clashing Cultures on Richard S. Ewell’s Road to Gettysburg (Kent: The Kent State University Press, 2018), 81-82.

Point taken. I am sure that there is much Maxwell missed about the Gettysburg experience. But there’s only so much you can put in one movie. Gettysburg was four hours long—it required an intermission.

Gettysburg also downplayed the female experience in the battle. I guess Jennie Wade’s death fell on the cutting room floor? According to the website for her museum, she “became Gettysburg’s heroine.” Should we fault Maxwell for ignoring her, and the other women of Gettysburg, as well?

Perhaps you’re being a wee bit picky here.

While including Jennie Wade’s story would have required lengthening the run time, it wouldn’t have required any special effort to include African Americans in the background in the numerous camp scenes and marching scenes. There were a lot of opportunities to show them. They did have women in some scenes as the armies marched along. I do fault the movie for ignoring other aspects of the battle too. But like you said, it could only be so long.

Thank you for detailing the true source of Southern wealth. Without free labor there would have been no oligarchs to demand the right to enslave men and women.

The sources are good enough that we could have a new film, with true and accurate characters!