Kilpatrick’s Shirt-Tail Skedaddle: The Battle of Monroe’s Crossroads, March 10, 1865

Conclusion of a series.

After rallying his troops, Kilpatrick found a ragged old nag of a horse, and ordered a counterattack by his men, who surged forward out of the swamp and engaged the Confederate cavalrymen. In the meantime, Lt. Stetson was able to man first one, and then other, of his guns near the Monroe house, taking the starch out of the Confederate attack. Butler ordered an attack on the guns, which was led by The Citadel Cadet Ranger Company of the 4th South Carolina Cavalry, led by Capt. Moses Humphrey. Leading his troopers forward, Humphrey and his horse were both felled by a blast of canister. The captain and his loyal steed were buried in the same grave. Lt. Col. Barrington S. King, the commander of the Cobb Legion Cavalry, was also mortally wounded by one of Stetson’s blasts.

Those blasts of canister served to rally the Union men. One of Kilpatrick’s troopers described the determined counterattack by the Union horse soldiers as “one of the most terrific hand-to-hand encounters I ever saw.” Blue and gray mingled promiscuously as they slugged it out for possession of the Union camps. One of Wheeler’s division commanders, Brig. Gen. William Y. C. Humes, was badly wounded in the leg, and a brigade commander, Col. James Hagan, lay on the ground bleeding from a severe wound.

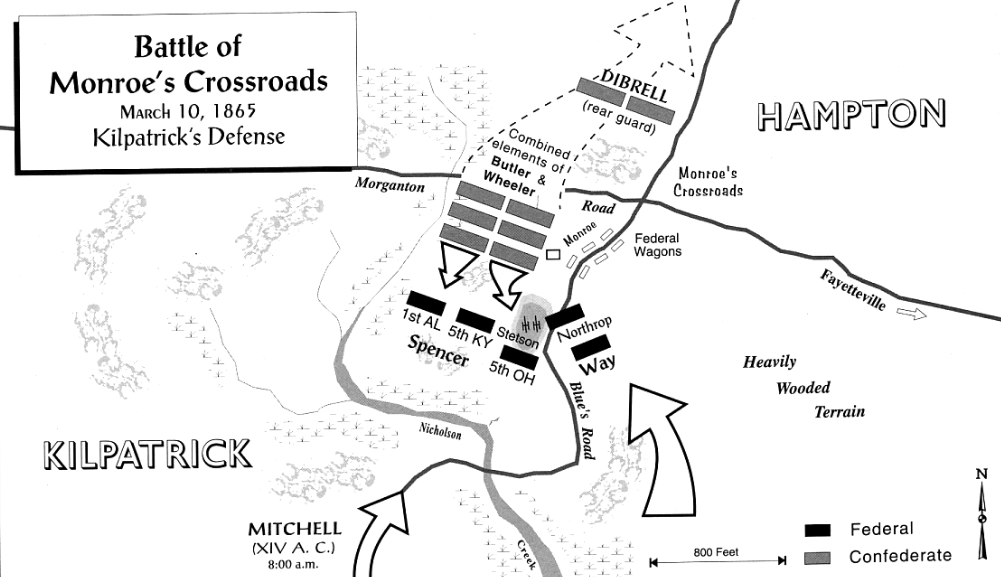

Kilpatrick’s determined counterattack re-took his headquarters at the Monroe House and then began shoving the Confederate cavalry back toward the Morganton Road. They also punished those elements of Wheeler’s corps that had gotten bogged down in the swamp for the better part of 90 long minutes. After taking heavy losses—Wheeler had lost two division commanders and two brigade commanders badly wounded—and realizing that he had done all that he could, Hampton finally ordered his command to withdraw. Law’s reserve troopers came forward to cover the Confederate retreat and were joined by Brig. Gen. George Dibrell’s late-arriving brigade of Wheeler’s corps, and these troopers fended off Kilpatrick’s final attacks and allowed the rest of the Confederate cavalry to break off and withdraw safely.

Kilpatrick was happy to let them go. Having been caught by surprise and having taken heavy losses, he was in no hurry to pursue the grayclad horsemen. His command spent the rest of the day licking its wounds. Maj. Gen. James D. Morgan’s 14th Corps Division arrived to reinforce Kilpatrick after the battle ended, and the Union commander soon became a laughingstock when the story of his flight into the swamp clad in only his nightshirt spread. The foot soldiers quickly dubbed it “Kilpatrick’s shirt-tail skedaddle,” not without merit. So ended the final major cavalry engagement in the Western Theater of the Civil War.

In the end, Kilpatrick won the battle by retaining the field at the end of the day, and having driven off Hampton and Wheeler. However, winning or losing the battle was not the issue. Hampton’s plan was designed to buy time for Hardee’s infantry to make its escape, and in that, the Confederates were wildly successful. By keeping Kilpatrick’s cavalry tied up for the entire day on March 10, Hardee was able to reach Fayetteville unmolested, and to cross his entire command safely. Wheeler’s troopers served as the rearguard, and the last of them to cross the Clarendon Bridge set it ablaze as the lead elements of Sherman’s army entered Fayetteville on the morning of March 11. The destruction of the bridge forced Sherman to halt in Fayetteville for several days until his pontoon bridges could be floated up the Cape Fear River from Wilmington. Hardee’s command pulled back and established three strong defensive positions at Averasboro, where his small command of less than 10,000 men successfully held off fully half of Sherman’s army for a full day on March 16, 1865 before withdrawing after dark that night. Hardee’s command then joined Johnston’s army at Smithfield the next day.

In short, the determined attacks by Hampton and Wheeler at Monroe’ Crossroads made the Battle of Bentonville possible. But for the bold surprise attacks that nearly destroyed Kilpatrick’s command, Hardee’s troops might have been brought to ground at Fayetteville and the Clarendon Bridge might have been seized by Kilpatrick’s troopers and made available for use by Sherman’s army, which might have arrived before Johnston could concentrate his army for the battle that became known as Bentonville.

This saga was well-written. Its analysis of Confederate strategy and tactics and the results of the battle made me realize what a juggernaut Sherman had created that in the end he was victorious against such a gallant and capable foe.