Jackson’s Arm and the Occupy Movement

A mythos is a set of beliefs or assumptions about something, and every hero needs to be surrounded by one. Confederate General Thomas Jackson has probably one of the best mythos anywhere, from eating lemons to last words. Did he really hold his hand in the air to balance his legs? What was all that praying about? Could anyone have had better nicknames than Jackson? “Ol’ Blue Light” alone is mythos at its finest, though “Stonewall” is best known.

And there is the arm . . . that transcendental body part which, over the last one hundred forty-eight years, has assumed its own set of myths. Currently, the arm is lost. No one knows quite where it is buried.

My favorite part of the Jackson “mythos within a mythos”–Jackson’s Arm–is the tale about Smedley Butler and the reburying of the arm in a metal box.

According to NPS historians, Jackson’s arm is somewhere in the Ellwood Cemetery, which is behind Ellwood Manor, on the grounds of the Wilderness National Battlefield. And that is all they will claim as truth. (For more on the NPS’s work with the arm, check out this three-part series.)

But the mystery is part of the fun, and part of that mystery—part of the mythos of Jackson’s arm—has become inextricably linked to Smedley Butler.

Smedley Butler was quite a man. He was a major general in the U. S. Marines, and at the time of his death, in 1940, he was the most decorated Marine in American history. How we lose track of our heroes amazes me.

He is one of only nineteen men to have received the U. S. Medal of Honor twice, one of only three to be awarded both the Marine Corps Brevet Medal and the Medal of Honor, and the only man to have been awarded the Brevet Medal and two Medals of Honor. He served in World War I, commanding Camp Pontanezen in Brest, France, and became the Commanding General of the Marine Corps Base in Quantico, Virginia after the war. Upon retirement, he ran for a Senate seat in Pennsylvania, but was defeated.

I had been thinking of him lately, as the Occupy Movement began to take up an increasing amount of news time, starting last fall. One of the planks of Butler’s Senate campaign concerned the Bonus Army.

The Bonus Army, grandfather (maybe even parent) to today’s Occupy movement, was the popular name for about 17,000 World War I veterans and their families, who gathered in Washington, D. C. in the late spring and early summer of 1932. They had come together during the depths of the First Great Depression to ask President Hoover to redeem their service certificates early.

These certificates, created by the World War Adjusted Compensation Act in 1924, were issued to qualified veterans, and had a face value of the soldier’s promised payment plus compound interest. Because many of the returning soldiers were out of work, the men felt that a redemption of the certificates would be one way to help them and their families through hard times.

There was much Congressional support for this, but Hoover & the Republicans reasoned that taxes would have to be increased to cover the payout, and this was something they were not willing to do.

Most of the Bonus Army made camp in a Hooverville (a pre-Occupy encampment) on the Anacostia Flats just south of the 11th Street Bridges–now Section C of Anacostia Park. On June 17, they marched from Anacostia to the United States Capitol to demonstrate for their cause, but the Senate defeated the Wright-Patman Bonus Bill, already approved by the House, by a vote of sixty-two to eighteen. Retired General Smedley Butler, learning of this political defeat, came to the encampment to back the effort and encourage the marchers. Apparently, he stayed for quite a while, getting their particular Hooverville shaped into a model military encampment, with proper latrines and regular streets, and checking the credentials of each marcher to be sure he had been honorably discharged from his term of service.

No government has ever been particularly hospitable to such demonstrations, then or now. On July 28, Attorney General William D. Mitchell ordered the veterans and their supporters off all government property. The Washington police showed up to enforce the Attorney General’s orders.

The police met with resistance from Bonus Army members, and shots were fired. Two veterans were mortally wounded. President Hoover then called in the regular U. S. Army to clear the veterans’ campsite.

The Army showed up, all right. Army Chief of Staff General Douglas McArthur commanded both infantry and cavalry, supported by six tanks. Among McArthur’s officers were Dwight Eisenhower and George Patton. The Bonus Army, made up of veterans from World War I, along with their wives and children, were fired on by the Army they had once joined. Be appalled. Be very appalled! Smedley Butler certainly was.

It is this Smedley Butler who, according to the mythos of General Jackson, reburied Stonewall’s arm. The story goes like this:

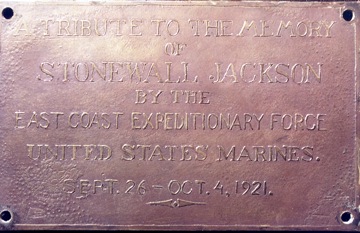

In 1921, the U. S. Marines conducted training maneuvers on farms adjacent to Ellwood Manor. Butler commanded these forces. He had heard about the arm burial, but was not sure if it was true. “Bosh! I will take a squad of Marines and dig up that spot to prove you wrong,” he is said to have declared. He then ordered a squad of Marines to dig beneath the marker erected by Jackson staffer Lieutenant James Power Smith, in 1903. To General Butler’s astonishment, the arm, buried in a long wooden box, was unearthed. Butler had the arm placed in a metal box and reburied, then ordered a bronze plaque noting the event to be cemented to the stone marker already in place.

Is this really true? Many claim it is, but there is doubt, especially on the part of the National Military Park Service. In 1998, after the NPS chose to open Ellwood Manor and surrounding lands to the public, there was concern that General Jackson’s arm might be a temptation to looters and grave robbers. To offset this possibility, it was decided to create a concrete covering over a larger area than just the identified “grave” site.

However, when the archeologists came to verify the placement of the arm, and of the Butler episode, no arm could be found. No box, no bones, no traces of remains in the soil–nothing. There was no evidence to prove that General Butler did anything at all about Jackson’s arm, or that Jackson’s arm had ever been in that particular place.

Currently, the NPS feels the arm is buried somewhere in the Ellwood Cemetery, but is not sure of the exact location. Butler’s plaque is no longer on the stone marker, but there are signs that it once was. The plaque can be viewed at the Chancellorsville Battlefield Visitors Center. It is inscribed, “A Tribute to the Memory of Stonewall Jackson.”

Currently, the NPS feels the arm is buried somewhere in the Ellwood Cemetery, but is not sure of the exact location. Butler’s plaque is no longer on the stone marker, but there are signs that it once was. The plaque can be viewed at the Chancellorsville Battlefield Visitors Center. It is inscribed, “A Tribute to the Memory of Stonewall Jackson.”

One of the arguments against the Butler story is that General Butler would never have disturbed military remains. Here is my counter to that argument: If General Butler’s quote is even partly correct, he felt there were no remains there anyway. He was attempting to prove the existence of a hoax, which he felt dishonored Jackson. When the arm, in its wooden box, was discovered, Butler quickly sought to make amends. He reburied the arm in a more substantial coffin, then added the plaque, as it says, in “a tribute.” If the entire story is only that–a story–why would there be a plaque?

That’s my mythos, and I’m sticking to it.

—————

Recommended Reading:

The Last Days of Stonewall Jackson by Chris Mackowski and Kristopher D. White. pp. 62-67.

http://usa-civil-war.com/Jackson/jackson_arm.html

http://www.historynet.com/visiting-stonewall-jacksons-left-arm-at-chancellorsville.htm

http://www.roadsideamerica.com/story/28903

Confederates In the Attic, by Tony Horowitz. pp. 230-236.

Please check out the recommended readings! All are both interesting and excellent. Check out the links within the post as well. This post was written to be part of a series, and an informative series it is.

Your mythos will be my mythos….and we’ll stick to it together! You have pulled all of this information together brilliantly! Thank you for all your research and insight!

Smedley’s most Occupy inspiring statement was in his 1933 book War Is a Racket:

“I spent 33 years and four months in active military service and during that period I spent most of my time as a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism. I helped make Mexico and especially Tampico safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street. I helped purify Nicaragua for the International Banking House of Brown Brothers in 1902-1912. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for the American sugar interests in 1916. I helped make Honduras right for the American fruit companies in 1903. In China in 1927 I helped see to it that Standard Oil went on its way unmolested. Looking back on it, I might have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he could do was to operate his racket in three districts. I operated on three continents.”

This is one of my favorite quotes–3 continents indeed! Glad to see someone else thought of General Butler as soon as Occupy started up!

Meg, I see you are writing on Ellsworth. Last summer I wrote an essay on three Union regiments after Bull Run, the Fire Zouaves, the 79th NYSM, and the 69th NYSM for an immigrant publication. You might find the extended appendix on the Fire Zouaves interesting. Frankly, I was shocked by the NY Times treatment of them.

http://www.longislandwins.com/index.php/features/detail/after_bull_run_mutineers_scapegoats_and_the_dead/

Great post.