“VMI Will Be Heard From Today”

“You may go forward, then.”

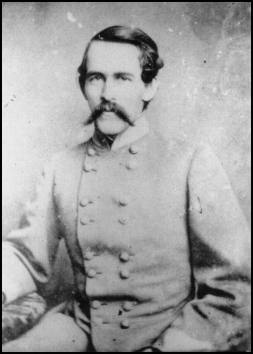

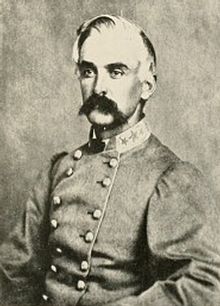

With those five words, Confederate General “Stonewall” Jackson ordered Brigadier General Robert Rodes’ division forward.

As Jackson had said earlier on the May 2, 1863, the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) would be heard from that day.

What VMI would have been especially proud of was the demeanor and personality showed by a 1848 graduate.

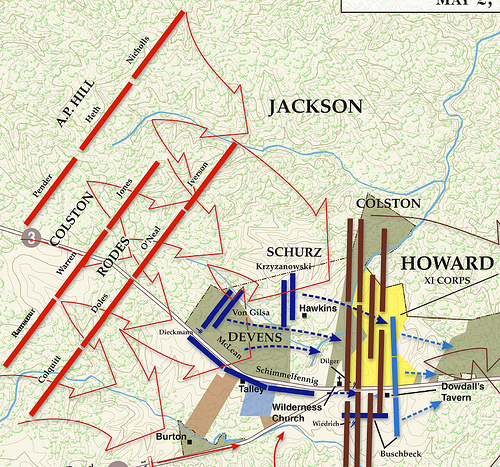

What history vividly remembers came after Jackson’s simple words. Rodes’ division was in the front line of 22,000 Confederates as they slammed into the exposed flank of the Union Army of the Potomac’s XI Corps. Chaos ensued. The Union army’s flank was pushed back more than three miles.

(Courtesy of CWT)

By nightfall, the Confederates had wrecked the flank but there was still reason for concern. The Union army still lay between the two wings of the Confederate army (General Robert E. Lee with approximately 14,000 had stayed to the east to occupy General Hooker and as large of the Union army as he could). The Confederates were still severely outnumbered, and if Hooker came to his senses he could easily turn on the Confederates and still gain victory.

In addition, Jackson’s Second Corps was realigning. Rodes’ division was being pulled back and Major General A.P. Hill’s division was coming up to take its place. To keep momentum though, Jackson rode out to do a reconnaissance and to make preparations for to continue the assault.

Before leaving with his staff on this fateful mission, the Confederate commander had this to say to Rodes in recognition of his division’s accomplishments that day.

“General, I congratulate you and your command for your gallant conduct and I shall take pleasure in giving you a good name in my report.”

What happened after Jackson rode out the Old Mountain Road is well-known. After hearing the sound of Union soldiers digging in, Jackson started making his way back to his own lines. Brigadier General James Lane’s brigade had taken over the area and had been told that any men ahead of them were the enemy.

When Jackson and his cavalcade approached, the edgy North Carolinians unleashed a volley and then another. Jackson was caught in the second volley, hit three times by friendly fire.

Command devolved onto the next in seniority, which was A.P. Hill. But within a short time he was also wounded when a shell fragment wounded him across the calves.

This meant that Robert Rodes, just recently promoted to command a division was now in charge of the Second Corps.

Rodes sprang into action and showed the promise of higher command he had seemed capable of during the first two plus years of the war. “Without loss of time” he subsequently turned his division over to his next in line and established a makeshift corps command.

The new corps commander then called in the other two division commanders; Raleigh Colston and Henry Heth (who had taken over Hill’s division). The three of them agreed to continue the attack the next morning, as Jackson would have wished. This showed prudence as Rodes wrote later, as it was agreed “that the troops were not in a condition to resume operations that night.”

And then as quickly as command fell to Rodes, it was taken away. Jackson’s chief of staff, Sandie Pendleton and the now-wounded Hill concluded that the responsibility of command would be too much for a recently promoted division commander.

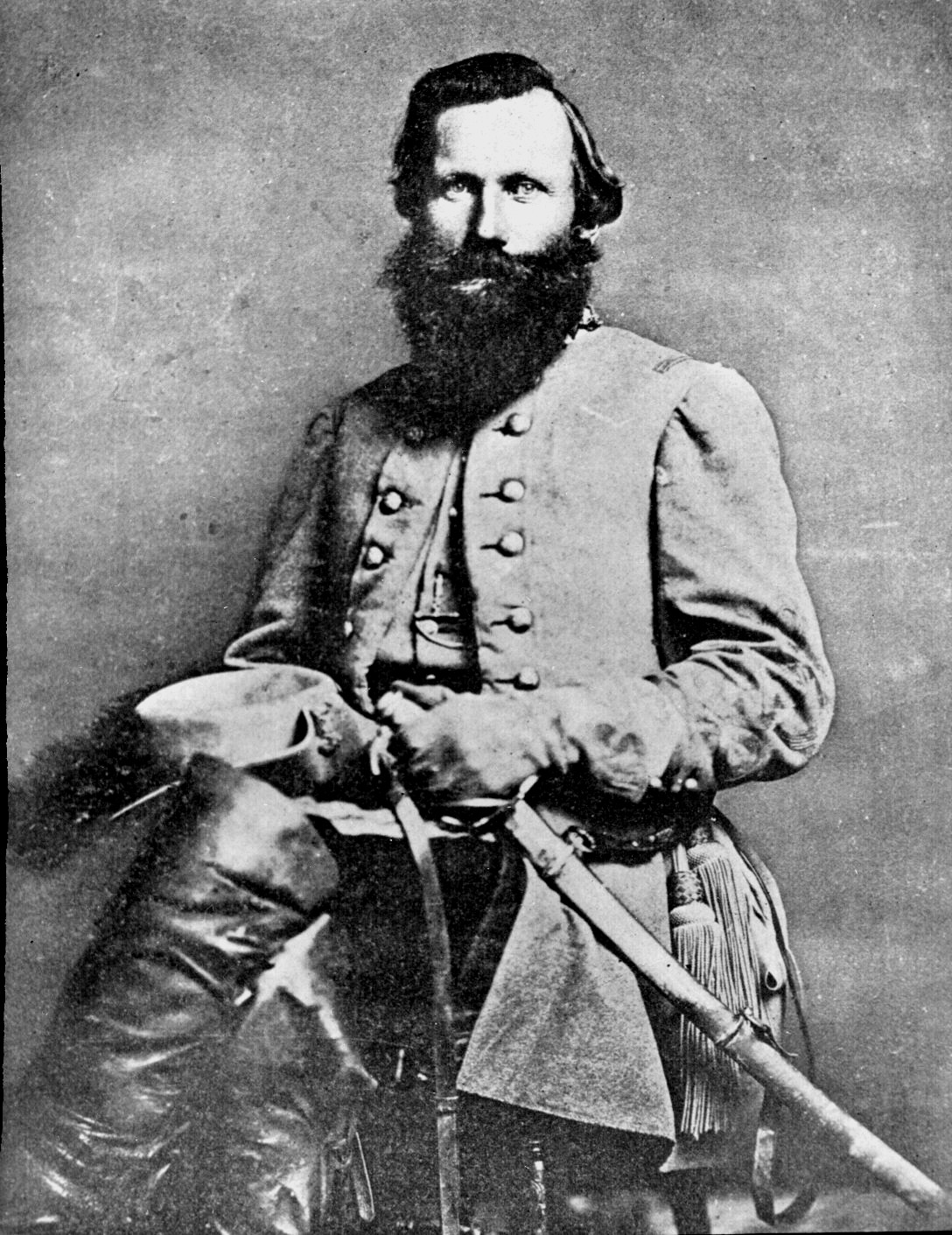

Both of these Virginians came to the thought that the only man who could keep morale up and also continue to keep morale up was only one man; the famous Confederate cavalier. With that they summoned by messenger Major General James Ewell “J.E.B.” Stuart to take command.

Rodes tenure then as corps commander lasted less than three hours as Stuart rode up around midnight to assume command.

However, Rodes did not have to give up command. As his biographer wrote “army regulations made no provisions for turning over an infantry corps to a cavalry officer.” Technically, Rodes could keep command, but he did.

With that Rodes showed more humility than any other Confederate commander in the war. Many talked about putting the cause first, yet, when that came to show, Rodes actually “walked the walk”. With that he showed an example to emulate.

He did explain his reasoning during his report of his action during the Chancellorsville campaign;

“I deem it proper to state that I yielded the command to General Stuart not because I thought him entitled to it, belonging as he does to a different arm of the service, nor because I was unwilling to assume the responsibility of carrying on the attack, as I had already made the necessary arrangements, and they remained unchanged, but because, from the manner in which I had been informed that he had been sent for, I inferred that General Jackson or General Hill had instructed Major Pendleton to place him in command, and for the still stronger reason that I feared that the information that the command had devolved on me, unknown except to my own immediate troops, would, in their shaken condition, be likely to increase the demoralization of the corps. General Stuart’s name was well and favorably known to the army, and would tend, I hoped, to reestablish confidence.”

The concluding sentence is the most telling as Rodes reiterated his for giving up command voluntarily and without incident.

“I yielded because I was satisfied the good of the service demanded it.”

Can one imagine this happening in the Confederate western army with the intrigue of the high command? Or even within the officer corps of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia where honor and rank sometimes bounded tightly officers’ emotions?

Now this is not saying that Rodes did not aspire to higher command or even covet it nearly as much as the next officer. But, his selfless act did not go unnoticed.

Henry McClellan, who served on Stuart’s staff, had this to say about Rodes’ deed.

“The history of war does not afford a more striking instance of magnanimous and patriotic self-sacrifice…[he] yielded the opportunity for personal distinction when he believed that the interests of his county so required.”

Friend and Rodes’ former staffer wrote after the war’s conclusion about what Rodes did on the night of May 2nd;

“Rodes exhibited conspicuously the noble spirit which ever actuated him during life…he was looking forward to a no less glorious morrow, when all the fruits of success would be gathered, to be laid by him at the feet of General Lee…the ambitions of this young general was sorely tempted. The command was his by military law, and he was conscious of the power to wield it loyally and well, but his love of country transcended his love of self, and he put the temptation aside.”

Others were a little more critical of how the transfer happened. Colonel Thomas Munford, a cavalry officer thought that Stuart’s promotion over Rodes was “a great piece of injustice.” Whereas others lamented that “Rodes threw away the opportunity of his life.”

Either way, Rodes, according to his biographer, meant exactly what he said in his report and his words “probably should be taken at face value.”

As we commemorate the 150th anniversary of the battle, there will be many human interest accounts that will be shared. Rodes will be talked about certainly, but what he did in the nighttime hours of May 2nd, could easily be overlooked.

But, what cannot be overlooked was what Rodes did for the good of the service. And in his own way, by allowing the charismatic and well-known Stuart to take command in time for the action the next morning, he played a major part in the ultimate victory at Chancellorsville.

As Jackson had said, “VMI will be heard from today.” And the university would have been proud to have heard about the character displayed by an 1848 graduate.

Sources & Further Information

To read further on Robert Rodes and which was used as a source for this post one should consult the excellent biographey written by Darrell L. Collins, titled “Major General Robert E. Rodes, of the Army of Northern Virginia.”

To read a review of Collins’ biography done by fellow ECW writer Chris Mackowski, click the following link: http://fredericksburg.com/News/FLS/2011/062011/06072011/628308/#

Lastly, check out the publications page and ECW Series books about “The Last Days of Stonewall Jackson” by Chris Mackowski and Kristopher White.