All Hallow’s Eve

All my friends know that I’m a “scaredy cat.” When a horror movie comes on, you can find me hiding beneath a blanket or behind the couch. To distract myself from this month’s “spooktacular” festivities, I did some research regarding Halloween during the years of the Civil War. Accounts of soldiers celebrating Christmas are common, but what about other holidays? Was Halloween an excuse to throw a party in the 1860s? After all, Halloween is one of the world’s oldest holidays dating as far back as 5 BCE (at that time it was known as “Samhain”).

This autumn holiday may have begun as a simple Pagan festival in which food for spirits was left on doorsteps, but today it has become an extravaganza of spooks. In the eighth century, Pope Gregory III declared November 1st “All Saints Day,” making October 31st “All Hallow’s Eve.” When the tradition arrived in America, only Maryland and the southern colonies participated. The Irish influx into the states spurred the popularity of Halloween. By 1850, Americans across the country were dressing up and knocking on doors in hopes of receiving food or money. Today we call this “Trick-or-Treat.”

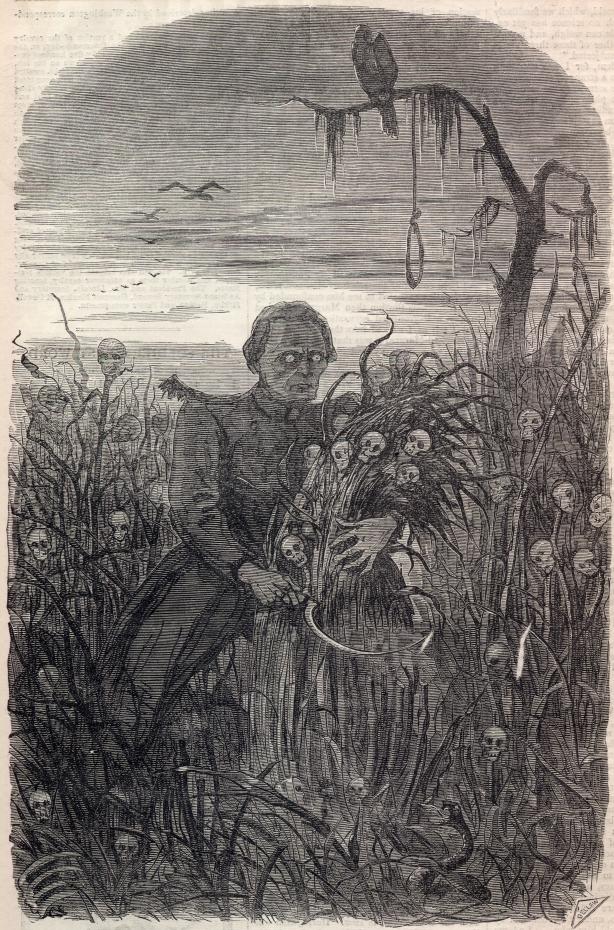

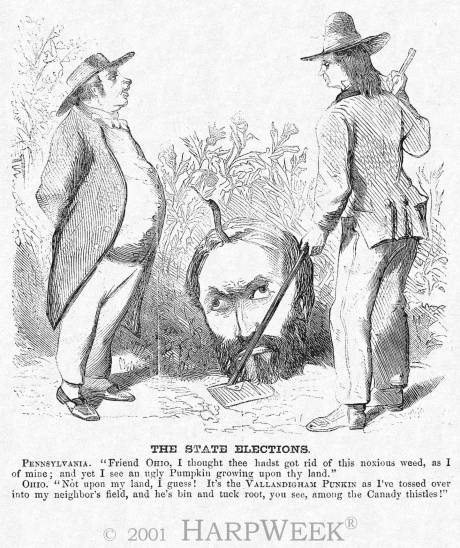

Though not like it is today, Halloween was in fact celebrated during the Civil War. If you look hard enough, you can find references to Halloween in the media. For example, Harper’s Weekly published the political cartoon “Jefferson Davis Reaping the Harvest” in October 1861. The ghoulish scene depicted the Confederate President gathering wheat topped with skulls. In October 1863, Harper’s Weekly published a cartoon showing Copperhead Clement Vallandigham as a pumpkin.

Another reference to Halloween can be found in The Peoria Morning Mail which included the following in it’s November 2nd, 1862 issue:

“All-Hollow E’en.”—This old time anniversary which took place on Friday evening, was made the excuse by some of our wild boys for throwing unsavory missiles, putrid vegetables; taking gates off of the hinges, and sundry other pranks. This was probably “good fun” to the boys, but for those thus attacked it was not so desirable. This is the way a “very quiet” night was spent as stated by a contemporary.’

In November 1864, Kate Stone wrote the following in her journal Brokenburn:

“Some gentlemen called, and we had cards. After they left, Lucy and I tried our fortunes in divers ways as it was ‘All Hallow’e’en.’ We tried all magic arts and had a merry frolic, but no future lord and master came to turn our wet garments hanging before the fire. There were no ghostly footprints in the meal sprinkled behind the door. No bearded face looked over our shoulders as we ate the apples before the glass. No knightly forms of soldiers brave disturbed our dreams after eating the white of an egg half-filled with salt.”

I can’t imagine the soldiers had much time to celebrate Halloween, but it’s interesting to think about how traditions have changed over the years. Even with the special effects we have today, it’s important to remember that no horror movie can compare to what American soldiers experienced during the Civil War.

On a side note, I hope you all have a happy and safe Halloween.

Check past Hallowe’en offerings! We scare up some good stuff here at ECW. I LOVE the pumpkinhead Vallandigham!

I’m curious as to whether these images were meant to evoke halloween, or if they’re just based on common seasonal practices that today would be connected to halloween. For example, Jefferson Davis reaping. That’s a seasonal image, not necessarily halloween.