The Absolution at Gettysburg

Today we welcome guest author Peter M Preble. Father Preble is a 2004 graduate of Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology where he concentrated on Church History. Since his graduation he has continued his research concentrating on the role of the Army Chaplain during the time of the Civil War. He has taught classes at Nichols College in Dudley Massachusetts and Quincy College in Quincy Massachusetts. He presently serves as Command Chaplain with the Massachusetts Organized Militia.

Nearly One Hundred and Fifty One years ago, two great armies were marching toward the small Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg. The inhabitants of this small town numbered only 2,400 souls and they were going to be in the middle of the one of the greatest battles of the United States Civil War.

From July 1st until July 3rd the Army of Northern Virginia with almost 75,000 men, commanded by General Robert E. Lee and the Army of the Potomac with almost 92,000 men, Commanded by Major General George G Meade, battled it out on this field that left more than 7,800 dead, 33,000 wounded, and more than 11,000 captured or missing. The ground literally was red with the blood of both blue and gray.

Although this battle has gone down in history as one of, if not, the bloodiest battles in American history, there is one little known event that took place on July 2nd in the middle of the battle.

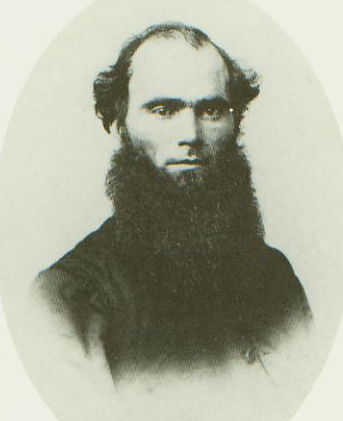

Father William Corby, Chaplain of the 88th New York Infantry Regiment of the Irish Brigade, had been with his men since the start of the war. He was living at Notre Dame University when the war began and became chaplain of the Regiment serving until the end of war. What was remarkable about this is that the average service of a Chaplain was 18 months as most of them were in their 50’s and just could not adjust to the life in the field and so most resigned their commission and returned home.

The role of the Chaplain in the Army at the time of the Civil War was unclear. They were appointed by the regimental commander after being elected by the field grade officers in the regiment. Most of the men elected chaplain were already known to the commanders and other officers of the regiment, but sometimes, as the case was with Fr. Corby, they came from other states. Chaplains were paid at the rank of Captain of Calvary $100 per month and $18 for rations. They were provided a tent, and forage for one horse, which they had to provide for themselves. Chaplains in the Confederacy did not fare as well. Most of them did not get paid at all.

Although chaplains were considered officers, they did not have command authority. Chaplains wore a uniform, “The uniforms for chaplains of the Army will be plain black frock coat with standing collar and one row of nine black buttons; plain black pantaloons; black felt hat or Army forage cap without ornament. On occasions of ceremony the plain chapeau de bras may be worn.” They wore no rank and carried did not carry weapons. If they were available an aide was provided to the chaplain to help him with his daily tasks. They were sort of caught in “no man’s land” between the officers and the enlisted. Often times they were alone and on horseback, riding between the companies of their regiment to bring spiritual comfort.

But what really sealed Fr. Corby’s place in history happened on the afternoon of July 2, 1863. The Irish Brigade was preparing to engage the enemy and Fr. Corby proposed to give the General Absolution to the men because, in his words, “the men had absolutely no chance to practice their religious duties during the past two or three weeks, being constantly on the march.”

In his book, Memoires of Chaplain Life, Fr. Corby quotes Major St. Clair Mulholland (Future Brevet Major General) of the 116th Pennsylvania Infantry regiment on his experience at this point:

“There are yet a few minutes to spare before starting, and the time is occupied by one of the most impressive religious ceremonies I have ever witnessed. The Chaplain of the Irish Brigade, whose members were mostly Catholic, proposed to give a general absolution to all the men before going to fight. Father Corby stood on a large rock in front of the brigade. Addressing the men, he explained what he was about to do, saying that each one could receive the benefit of the absolution by making a sincere Act of Contrition and firmly resolving to embrace the first opportunity of confessing his sins, urging them to do their duty, and reminding them of the high and sacred nature of their trust as soldiers and the noble object for which they fought. As he closed his address, every man, Catholic and non-Catholic, fell on his knees with his head bowed down. Then stretching his right hand toward the brigade, Father Corby pronounced the words of the absolution:

Dominus noster Jesus Christus vos absolvat, et ego, auctoritate ipsius, vos absolvo ab omni vinculo, excommunicationis interdicti, in quantum possum et vos indigetis deinde ego absolvo vos, a pecatis vestris, in nomni Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti, Amen

Authors Translation: Our Lord Jesus Christ absolve you, and I, by his authority, absolve you from every bond, excommunication, interdict, and in so far as I can and then I will absolve you, from your sins, in the name, of the Father, and of the Son, and the Holy Ghost, Amen.”

All of this took place within view of the Peach Orchard and Little Round Top with canon and musket fire all around them. Father Corby did what he could to prepare the men under his care for battle that day and for what would face them in the next world. There exists now a statue of Father Corby perched upon a rock, within 300 yards of where he gave this absolution at Gettysburg National Military Park.

To quote again from Father Corby’s book;

“I do not think there was a man in the brigade who did not offer up a heart-felt prayer. For some, it was their last; they knelt there in their grave clothes. In less than half an hour many of them were numbered with the dead of July 2nd.”

This past July, thousands of people traveled to Gettysburg, many of them traveling on the same roads that those soldiers did more than 150 years ago, to bring honor to those who gave the ultimate sacrifice on that ground. They go to reenact one of the bloodiest days in American history. They do this to honor those who fought on both sides for what they thought was right. Those who wore blue and those who wore gray were fighting for their version of America, for their rights and the rights of others. Some believe the war was inevitable and sooner or later it would happen. I cannot help but think of the priest from Notre Dame who stood on that rock and gave what comfort he could.

Father Corby has been quoted as saying that he meant this absolution not only for those assembled before him but for all of those fighting on that day that they fight the good honorable fight.

Father Corby died in 1897 after serving as President of Notre Dame University. The men he served with loved him very deeply and always invited him to speak at reunions and other gatherings that he was able to attend.

We must never forget our history and we must never forget those who gave so much for America.

(If you desire the footnotes for this article, please email Emerging Civil War.)

There are 2 statues of Father Corby. The one at Gettysburg where he is called Father Corby, and the one on the campus of the University of Notre Dame, where he is known as “Fair Catch ” Corby.