The Confederate Dead of Alsop Farm

I have stared at the Confederate dead, laid out in a long neat row, for entire summers, but still they have yet to reveal their stories to me. All I really know is that they were killed on May 19, 1864 during the battle at Harris Farm and that their bodies were laid out for burial at the Alsop house, adjacent to that part of the battlefield. They were the tattered remnants of the once-proud Confederate Second Corps, reduced to a shell of its former self and, here, these men, reduced to husks. They keep their stories to themselves.

I have stared at the Confederate dead, laid out in a long neat row, for entire summers, but still they have yet to reveal their stories to me. All I really know is that they were killed on May 19, 1864 during the battle at Harris Farm and that their bodies were laid out for burial at the Alsop house, adjacent to that part of the battlefield. They were the tattered remnants of the once-proud Confederate Second Corps, reduced to a shell of its former self and, here, these men, reduced to husks. They keep their stories to themselves.

Day after day, I have worked at the Spotsylvania Battlefield exhibit shelter, sweltering in that little brick baker’s oven in the high, humid Virginia summer. On the northeast wall of the shelter, in an exhibit panel that discusses the toll of battle, these men have been used to illustrate the grim costs. As the old saying goes, the death of an individual is a tragedy; the death of millions is a statistic. And so it goes with this exhibit panel: these men have been reduced to a representative illustration.

But I have studied them for long stretches, wondering about their tales. Who were they? Who did they leave behind? Who were the wives and the mothers and the sons and daughters who grieved for them? What were those last minutes like, caught in that firefight at Harris Farm, desperately holding on until dark as increasing numbers of Federals pressed in?

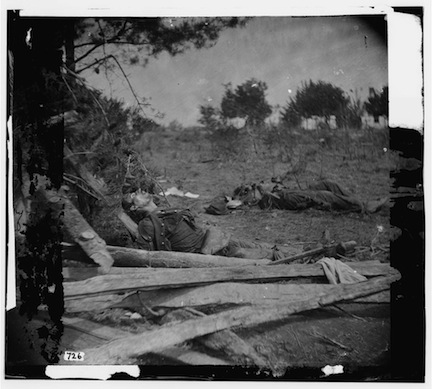

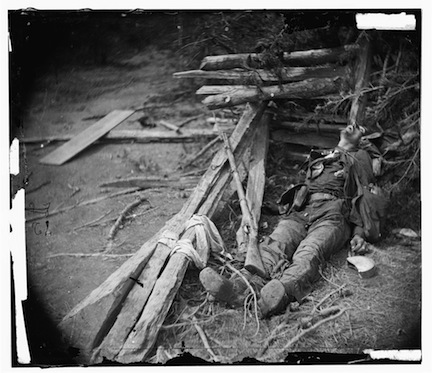

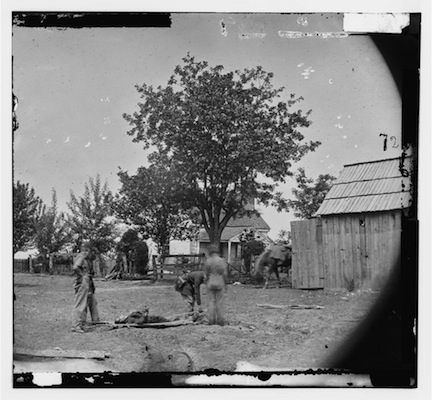

Photographer Timothy O’Sullivan captured these men on film on May 20—the day after the fight. They had been collected by Federal burial parties and lined up neatly for disposal.

The Irish-born O’Sullivan had photographed battlefield dead before, most notably at Gettysburg. In the spring of 1864, he was working for photographer Alexander Gardner, who was taking pictures in Fredericksburg at the time while O’Sullivan traveled with the army.

As O’Sullivan began to wander the Harris Farm battlefield, he found more dead scattered about the property, not yet collected. In a move that might seem appalling to modern media ethicists, he placed props in the photos to create more dramatic images. Of particular note was a musket that he carefully placed in his photos—across a Confederate’s body in one picture, across a snakerail fence in two others.

Last year, one of those dead Confederates found his way to the cover of a book Kris White and I co-authored, Season of Slaughter, which tells the story of the Spotsylvania battle. “One thing is certain of this campaign thus far,” said surgeon Daniel Holt of the 121st New York infantry, quoted at the beginning of the book, “and that is that more blood has been shed, more lives lost, and more human suffering undergone, than ever before in a season.”

And I realize that on the book cover, the dead of Harris Farm have—once more—been reduced to archetypical illustrations.

So I study this man. Again I wonder who he might have been. Rigor mortis has frozen both his forearms skyward, but he’s not reaching for anything. Instead, the fingers of both hands rest daintily across his palms as though some delicious dinner has been laid before him and he’s been taken aback in delight. On his right hand, his index finger sticks out just a little as though he’s trying to raise a point of order. “Excuse me: we’re not ‘The Dead of Spotsylvania.’ I was somebody’s son.”

The man’s face looks peaceful. With the haversack under his head, he could just be stretched out on a blanket, daydreaming away a summer afternoon, the warm sun sticking his hair to his forehead with sweat. He could be sleeping—a deep and restful sleep and not the sleep of forever.

O’Sullivan took six photos as part of his series. He had to be up close and personal with these dead men. Or did he see them merely as corpses? Did he objectify them so he could work–abstracting them as “the enemy” in order to give himself some emotional distance?

I imagine him working with the care of an artist–but he had to hurry, too. Burial parties were scooping up the bodies for burial, and the army was getting ready to move out. He had time to take a total of six pictures in the series before he had to pack up.

In one of his images, a burial party stands around a dead Confederate on a stretcher. Three of the four Federals are blurs of movement even as they seemingly stand still to look down on the corpse, which is clear and stone still even though the man looks like he’d been flash-frozen while midway through an electrocution. His back arches and his chest is thrown upward in a single, painful jerk. The one Federal not blurred by motion has been captured in mid-movement, bending over to grab the stretcher, his face hidden behind one of his compatriots. The movement and the stillness, the blur and the focus—they men are the quick and the dead. It’s all just a little much for me the longer I stare at it.

How does one wrap one’s mind around the scope of the carnage? How can one truly understand the magnitude of the slaughter?

Anonymous though those men may be, perhaps they did not die in vain if they’re able to put a face for us on that abstract horror.

Civil War photography brought the war to the doorsteps and homes of America, as The New York Times once said. On May 20, 1864, with the war brought to the doorstep of Susan Alsop’s house, Timothy O’Sullivan took photos that continue to bring the war to us 150 years later.

The challenge remains for us to see it.

With the sensibilities of the time–their time– n mind, I offer that these men are Heaven-bound, having died a good death in a righteous cause. Home folk miss them, but knowing they stood for duty and honor meant much more to people then than it does now.

Amen to that sister….well, some of us still respect their sense of duty and honor, outdated as our current society considers it.

I have seen the picture of the solder by the fence colorized, which makes it seem more modern. Even though 150 year’s ago, these are still America’s war dead, north and south, and should be mourned and remembered as we do our current losses in the Middle East.

My cousin was one of the Confederates killed there that day and I have always been fascinated by the images. I can find no photo of him in life, so he could very well be among these.

I also lost my Uncle PVT. Charles Remick from company B MA First Heavy Battalion here on this day. I wish they had taken more pictures of the Union losses. Such a senseless waste of life for all that loss family in this Campaign.

Jonathan Swisher

Locations of the pictures taken at the Alsop farm-see article

http://spotsylvaniacw.blogspot.com/2011/03/placing-some-of-dead-at-widow-alsops.html

That next-to-last image, the one with the corpse on the stretcher at center, was adapted by Walton Taber as a pen-and-ink illustration for the “Battles and Leaders” series for Century Magazine.