“How Will We Feed Our Family?”

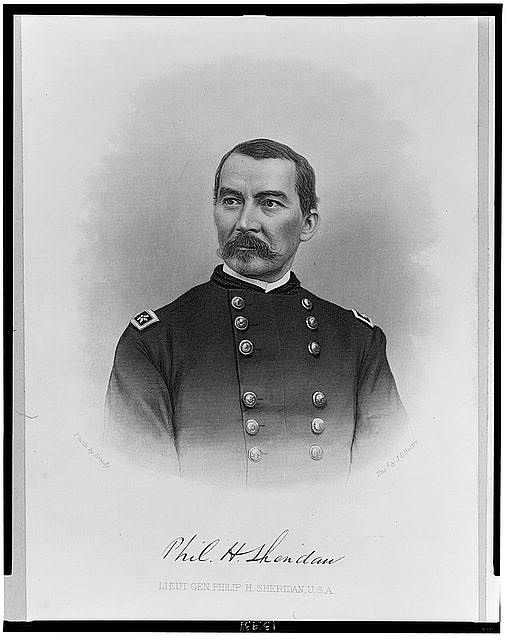

After the defeat of the Confederate Army of the Valley at the Battle of Fisher’s Hill on September 22, 1864, Union Major General Philip H. Sheridan began to carry out the next directive of his orders: to “eat out Virginia clean and clear…so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry its own provender.”

By the fall of 1864, prior to and as William Sherman’s forces began to cut a swath through Georgia, Sheridan instituted the same policy in the bucolic Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. The same principles were instituted: to make it “desirable that nothing should be left to invite the enemy to return.” The upper echelon of the Union war machine realized that destroying the Confederacy’s ability to make war was another way to quicken the end of the war.

With that directive, Grant and Sheridan put the residents of the Shenandoah Valley directly in the cross hairs of the next part of the campaign.

Within days, reports such as the September 29th missive from Sheridan to Grant that read, “7 miles of track [from the Virginia Central Railroad], depot buildings, government tannery, large amounts of leather, flour, and other stores” had been confiscated from Confederate military depots in the central Shenandoah Valley town of Staunton.

Another two-day period saw the blue-clad troopers of Sheridan’s cavalry forces torch “630 barns, 47 flour mills, 4 saw mills, 1 woolen mill, 3 iron furnaces, and 2 tanneries.”

Operating in the Luray Valley and guarding the eastern flank of Sheridan’s forces was the cavalry division of William Powell. The “fire demons” of his command torched a Confederate government contracted tannery owned by Peter Borsk that was worth approximately $800,000 dollars.

Wesley Merritt was in charge of another of the divisions of cavalry under Sheridan and he estimated that the destruction and waste his command wrought on the Valley was totaled at $3,304,672.

In a 92-mile stretch, Sheridan’s forces visited such destruction that it surpassed any “fury” a “natural force” had or could ever bring to the same area.

(courtesy LOC)

The Union forces could be tracked by the “cloud of smoke” that “marked the passage of the Federal army.”

“Millions worth of property was destroyed–arms, ammunition, clothing, rations, saddles, horse equipage, and government goods of every description.”

The Valley was becoming a “barren waste” to use the term Sheridan reported to Grant with.

A central Shenandoah Valley county, Rockingham, one of the largest counties in the entire state of Virginia, gives credence to the level of destruction and waste that the blue-clad soldiers visited.

A special committee was formed to calculate the “barren waste” that Sheridan left behind. Withstanding personal belongings and other miscellaneous smaller outbuildings, the blue-clad soldiers laid waste to

- 30 dwelling houses were burnt

- 450 barns burnt

- 100 miles of fencing destroyed

- 31 mills

- 3 factories

- 1 furnace

Besides what was burnt and destroyed, the following livestock and goods were removed or consumed by the Union troops

- 1,750 head of cattle

- 1,750 horses

- 4,200 sheep

- 3,350 hogs

- 100,000 bushels of wheat

- 50,000 bushels of corn

- 6,332 tons of hay

And this was just one single county.

Sheridan had vowed that when he was done with the “Breadbasket of the Confederacy” the area would “have little in it for man or beast.”

“Total War” had visited the bucolic Shenandoah Valley. The Confederate Army of the Valley, under Jubal Early would march through this now barren wasteland on the way to a climatic engagement on October 19, 1864.

Would “The Burning”—as this part of the campaign would become known as—play a part in what would happen along the banks of Cedar Creek?

Another area of the South was being laid to waste by the “total war” philosophy.

More soldiers in Confederate service would be faced with letters, with summons, with the very heartfelt yet basic question from home:

“How will we feed our families?”

*Today Historic Edinburg Mill, one of the few mills that survived the torches of Sheridan’s cavalry in 1864, still stands today. A visitor center, museum, and film, provide valuable information and context to what “The Burning” was for the populace of the Shenandoah Valley.

To plan your visit to the Edinburg Mill, click here.

Nicely done. I recently traveled to this area to see the mill built by my ancestor, Andrew Zirkle, in Forestville (just 23 miles from Edinburg) and was unaware until this post of the existence of the Edinburg Mill. The Zirkle Mill, too, was spared from the burning. The story goes the mill owner was a Unionist, and, seeing columns of smoke rising from neighboring mills, promptly retrieved and affixed an American flag to the mill, persuading troopers under Custer’s command not to torch the mill.

This country decries waging war on civilians yet they laid waste on fellow Americans. These couple of incidences of the feds sparing a mill or 2 because veterans of prior wars owned them doesn’t make up for waging war on women, children and old men, burning them out of their homes, great and small, leaving them to starve to death. Today, they would all be war criminals.