A Sharp Fight: The Battle of Farmington

On the morning of October 7, 1863, the Confederates of Henry B. Davidson’s cavalry division awoke to the urgent sounds of rifle and carbine fire. Davidson’s men were camped along the south bank of the Duck River, just a few miles east of Shelbyville Tennessee. Farther downstream lay the camps of William Martin’s and John Wharton’s divisions, comprising the remainder of Joseph Wheeler’s Cavalry Corps. For a week, Wheeler’s troopers had been rampaging through Middle Tennessee, one step ahead of their pursuers. Now several thousand Federal cavalry had caught up to them.

On October 1, Wheeler and nearly 6,000 Confederate cavalrymen crossed the Tennessee River above Chattanooga, embarking on what would be Braxton Bragg’s most significant offensive effort in the wake of the battle of Chickamauga. William S. Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland, though defeated, was not destroyed. Once ensconced behind their impressive earthworks, the Federals were proof against direct assault.

Bragg turned instead to the idea of severing Rosecrans’ tenuous supply line, and to do so, he turned to his chief of cavalry. Wheeler took all the fit men and animals he lay hands on, including three of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s four brigades, despite Forrest’s objections. For his part, Forrest took leave. He would not go on the expedition.

The raid began with a series of heady successes. The river crossing caught the Union cavalry unawares, allowing Wheeler to also slip over Walden’s Ridge. The next day, at a place called Anderson’s Crossroads, half of Wheeler’s column obliterated a Union supply train, headed into beleaguered Chattanooga. Wheeler destroyed between 500 and 800 wagons, killed something like 1000 mules, and took many prisoners.

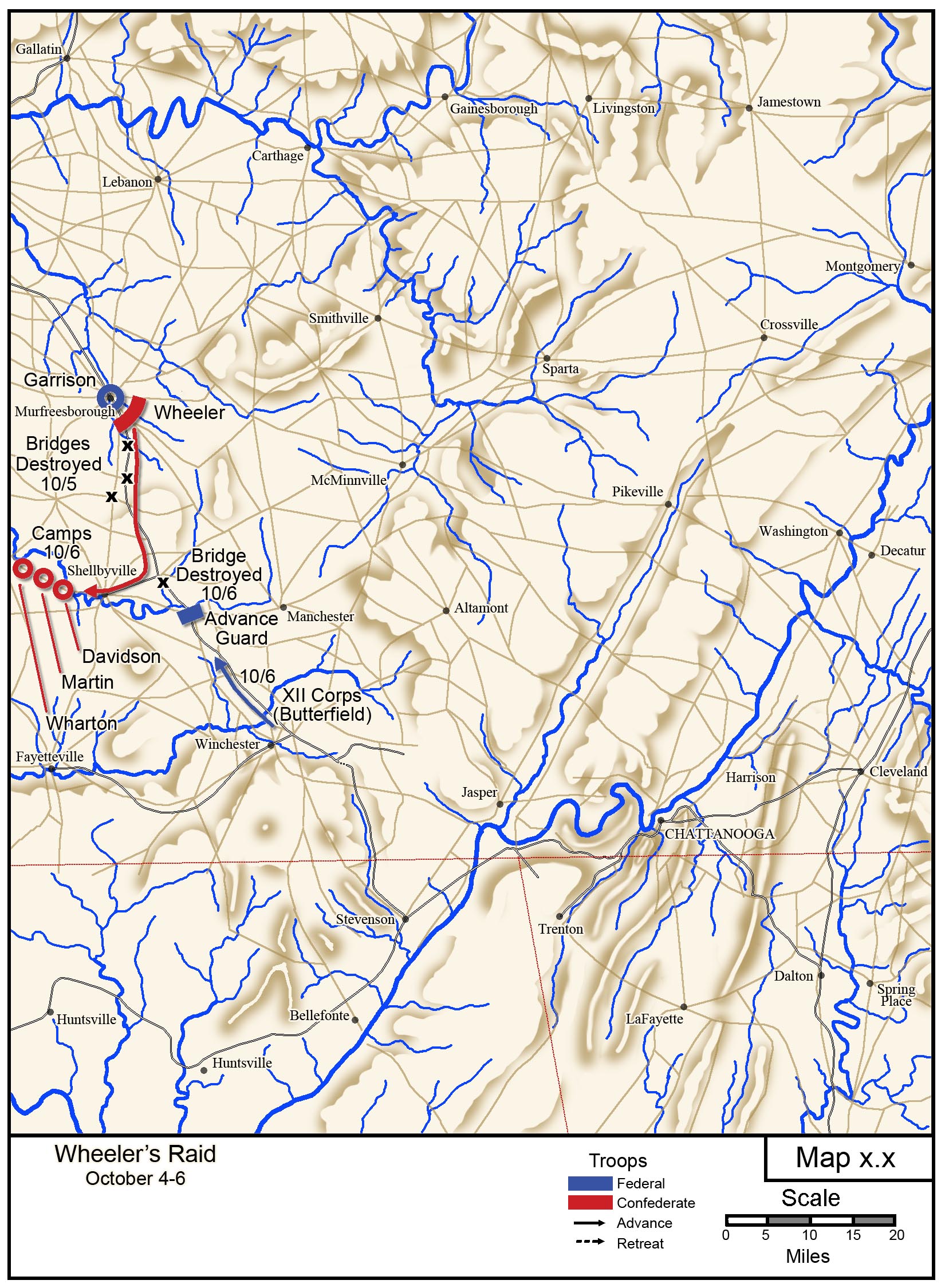

Union cavalry under Edward McCook caught up to Wheeler at the tail end of this spree, snapping up several hundred Confederate stragglers, including a number of men drunk on captured whiskey. The bulk of the Rebel column escaped fast-closing Federal pincers, however, and headed across the Cumberland Plateau towards McMinnville, a Union outpost and supply depot.

On October 4, McMinnville surrendered, yielding up another 400 Federal prisoners and additional warehouses full of supplies. This would be Wheeler’s last major success, however, for McCook’s Union division, now joined by George Crook’s division and Wilder’s famous Lightning Brigade of mounted infantry (commanded by Col. Abram Miller, since Wilder was on sick leave) were hot on Wheeler’s heels.

The next day, Wheeler attempted to repeat his McMinnville triumph at Murfreesboro, site of Fortress Rosecrans, the vast Union base established in the spring of 1863. The Murfreesboro garrison refused to cooperate, refusing Wheeler’s surrender demand. With Union cavalry closing in on his rear, and with the railroad now swarming with Federal infantry (most of them from the Union XI and XII Corps, transferred from Virginia) Wheeler turned south. It was time to head home.

On the 6th, Rebel cavalry burned several small railroad bridges south of Murfreesboro, and looted the town of Shelbyville. they then slipped westward towards the hamlet of Farmington. That night all three divisions, now with a combined strength of between 4,500 – 5,000, made their camps along the Duck. The next morning at dawn, George Crook and Colonel Abram Miller surprised Wheeler’s cavalry. Crook led the direct advance west from Shelbyville, while Edward McCook’s First Cavalry division came down on Farmington from the north, via Unionville. The plan was to trap Wheeler on the road between Shelbyville and Farmington.

Davidson’s men were surprised and routed. Will Martin’s two brigades made a more determined stand just east of Farmington, which bought just enough time for Wharton’s division to evade McCook’s pincer. A desperate, day-long fight ensued. Wheeler would later dismiss his losses here as small, but in fact the Federals, despite being outnumbered, inflicted punishing casualties on the Rebels.Their loss would have been larger had Crook managed to bring up Robert H. G. Minty’s cavalry brigade from the south and complete the trap. Minty, however, never got his orders, a situation which would later result in considerable enmity between the two men.

As cavalry battles go, Farmington was on the larger side. 4,500 Rebels faced 3,500 Yankees, and had Minty come up, that figure would have risen to 5,000 bluecoats. Federal losses amounted to about 150-200 killed and wounded. The Confederate losses went unreported, reported, but were certainly higher. Federal reports claimed 450 prisoners and a battery of artillery while Miller noted that his men counted 86 enemy dead on the field.

By October 9th, Wheeler re-crossed the Tennessee River deep in Alabama. A supporting raid mounted by Brigadier General Philip Roddy failed to achieve any important results, while an additional effort, to be launched by Brigadier General Stephen D. Lee out of Mississippi, never got off the ground.

While Wheeler did inflict important damage on Rosecrans at Anderson’s Crossroads and again in capturing McMinnville, he did not achieve Bragg’s intended result: starving Rosecrans out of Chattanooga. Further, Wheeler lost perhaps as much as a third of his force to combat, capture, and desertion: 2,000 out of 6,000 men. Federal cavalry, despite having equal or lesser numbers, managed to best Wheeler in a number of fights. They demonstrated that no longer could Rebel column raid with impunity.

Perhaps the most significant effect of Wheeler’s incursion was to delay the arrival of those Union infantry reinforcements from Virginia. Had Wheeler not launched his raid, The Union XI and XII corps might well have been ready to cross the Tennessee at Bridgeport much earlier than the end of October. Had they done so, and opened the Cracker Line into Chattanooga two weeks earlier, Rosecrans might have kept his job. As it was, Ulysses S. Grant relieved William Rosecrans of command of the Army of the Cumberland on October 19, a scant ten days after Wheeler re-crossed the Tennessee.

Superb reading ! Thanks Little Powell !

My mother was born in 1910 in the house just west of the crossroads of TN-271 and TN-40 (old Hwy 64). My great-aunt “Sue’s” house just across the road is visible in the Google Street View but is gone in the aerial view. Many happy Sunday afternoons at “Aunt Sue’s” after the most wonderful chicken dinners.

Don’t know if the “Brownie Ensley” house is pre-War.

Samuel Johnson, 17th Indiana Mounted Infantry, and his brother, William Johnson, were at Farmington. Unfortunately Samuel was killed during the action there. Samuel and WIlliam were descended from my Tracy ancestors.

Does anyone know if this engagement possibly made it down the area of what is now Hunter rd? Just curious as I live on this rd and am now learning about this engagement and wishing to learn more! Thanks.