“This city is now in the possession of the Confederate States of America”: The Raid on St. Albans, Vermont

On October 15, 1864, two men arrived in the town of St. Albans, Vermont and checked into a hotel named the American House. They appeared to be unassuming, but the two were the vanguard of some twenty others, all who arrived in the coming days to seat of Franklin County, Vermont. Dressed in plain clothes, and concealing Southern accents, the score or so of men were raiders, come to St. Albans, population of about 4,000 people, to strike in the name of the Confederacy.[1]

The raiders’ commanding officer was 21-year old Bennett H. Young, who, despite his age, had already seen plenty of action. Young was born in Kentucky and had served with John Hunt Morgan during the latter’s raid into Kentucky, Indiana and Ohio in the summer of 1863. Captured at the end of the raid, Young was sent to the infamous Camp Douglas, in Chicago.[2]

After he escaped from the prison, Young made his way to Halifax Canada, onto a blockade runner, and back to the Confederacy. Back in the South, Young had managed to convince higher-ups of the feasibility of an attack branching down from Canada.[3]

As part of Great Britain Canada was included in the official neutrality that Queen Victoria had declared on May 13, 1861, writing, “And whereas we, being at peace with the Government of the United States, have declared our royal determination to maintain a strict and impartial neutrality in the contest between the said contending parties [the United States and the Confederacy].” Yet as actions would show, Canada was hardly neutral in its dealings with Confederate agents, especially Bennett Young and his fellow raiders.[4]

Located just fifteen miles from the Canadian border, St. Albans was the perfect target for the rebels. Convened in the town with fake backstories, the raiders were careful to hide their Southern dialects in the days leading up to the attack. The objective: hit the town’s banks, rob the safes, and gallop back to the neutral Canadian border before there was any time for a pursuit to be made.

The original day planned for the raid was supposed to be October 18, but the raiders were taken aback when they awoke to find that it was Market Day in Franklin County. Scores of farmers brought their goods to St. Albans to sell and barter—with the increased number of men in the town an attack was out of the question. If there was any good news to the delay, the Market Day at least meant that the town’s banks would be full of cash. Young moved his plans one day to Thursday, October 19.[5]

The morning of the 19th saw the raiders, dressed in plain clothes, make their way to the center of the town. Young had split his men up; of the twenty or so he had, five or six each would attack the three banks, a small handful would hold their horses, and two would guard over any civilians who, according to the plan, would be herded to the town green.

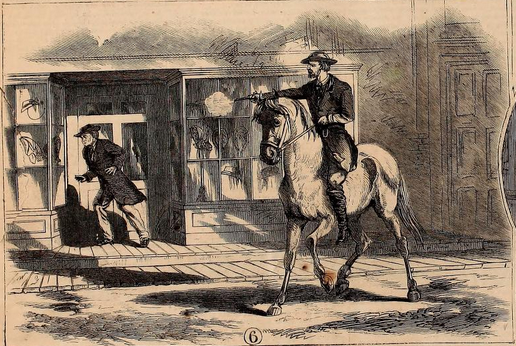

It was just after 3 pm when the raid got underway. According to a sensationalized memoir that gets more wrong than it does right, Young stood on the front steps of the American House, pulled out his .36 Navy pistol and announced to passerby that, “This city is now in the possession of the Confederate States of America!”[6] Whether or not Young said the words, the raid was underway and there were now twenty Confederate agents riding through the streets of St. Albans, Vermont.

The St. Albans Bank, the Franklin County Bank, and the First National Bank “were situated within a block and a half of each other around the town green,” allowing the raiders to quickly leapfrog from one to another.[7] The rebels worked quickly, first bursting into the St. Albans Bank and demanding money from the safe. Up to that point, there was nothing to distinguish the men from Confederate soldiers to the common criminal; they wore plain clothes and flew no flag. One of the bankers later said, “They presented nothing in their appearance or dress to lead to the belief that they were soldiers, unless it was their possession of revolvers.”[8] Yet as one of the raiders shoved his pistol in the banker’s face, there was little confusion for long as the man growled, “We’re Confederate soldiers detailed from General Early’s army to come north, and to rob and plunder as your soldiers are doing in the Shenandoah Valley.”[9]

The ultimate coincidence to the raiders’ menacing stance was that at the very moment that they were robbing the citizens of St. Albans, Jubal Early was being defeated at the Battle of Cedar Creek. Around the same time as the raid’s beginning, but 600 miles to the south, Phil Sheridan was unleashing his knockout counterattack.[10]

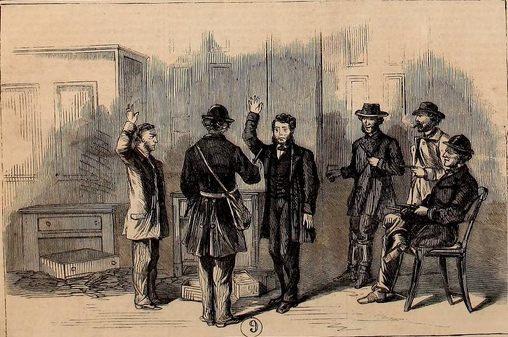

Before leaving the St. Albans Bank and moving on to the others, the raiders pushed the bankers up against a wall and forced them to raise their hand. Then the raiders made the Vermonters pledge to “solemnly swear to obey and respect the Constitution of the Confederate States of America.”[11]

The other robberies went along similar lines, and the raiders were soon ready to depart the town. And it was around this time that the only fatal wound from the raid occurred. Standing on some scaffolding, Elinus J. Morrison had called out a warning to some other civilians when one of the raiders pointed his pistol and fired. The bullet “passed through his left hand, which was in his pocket. It then pierced his body, punctured his intestines, and screeched to a stop near his spine.”[12] The 52-year old died two days later. Later, one of the raiders, Alamanda Bruce said, “I am told I am accused of having shot Morrison… if I had shot him it was my duty to do so.”[13]

Having stolen “more than $200,000” the raiders galloped off towards the Canadian border.[14] For the town of St. Albans, the raid could have been much worse. Armed with incendiary devices called Greek Fire, the raiders had thrown the bottles at various buildings, but the recent rains extinguished most of the fizzling and popping liquids before a great conflagration could break out. The lone building burned down was a farmer’s shed near the town green.

Riding hard on the raiders’ heels was 19-year old George Conger, a former captain in the Union army. With a quickly rounded-up group of St. Albans citizens, Conger set off for Young’s raiders. It was not very hard to follow the rebels—money was leaking out of some of the bank bags, leaving “a trail like Hansel and Gretel.”[15]

Reaching the Canadian border, Conger did not stop. He was furious at the raid; Morrison lay mortally wounded and two other citizens had been lightly wounded. The former captain, still but a teenager, broke Canadian sovereignty as he followed. As darkness fell on the 19th, Conger caught up to the raiders and arrested Young, finding the raider in a barn. At first, Young surrendered willingly, but upon realizing that the angry Vermonters might hang him from the nearest tree, struggled. His savior appeared in the form of a British Army major, alerted to the scuffle. Conger and his posse had no choice but to give up their prisoners and retreat back to the American border.[16]

So began months of politicking between the United States, Canada, and Great Britain. The United States, understandably wanting the raiders back to charge as common criminals, asked that Young’s men be extradited. But, in December, a trial of extradition in Montreal released the prisoners.[17]

The fury over the raid, and the ongoing trial went to the top of the United States Executive Branch. When Abraham Lincoln gave his annual message to Congress, the raiders would not be released for another week, but the sentiment was still clear when Lincoln threatened that the attacks stemming from Canada must be halted. At the height of his speech, Lincoln proclaimed, “In view of the insecurity of life and property in the region adjacent to the Canadian border, by reason of recent assaults and depredations committed by inimical and desperate persons, who are harbored there, it has been thought proper to give notice that after the expiration of six months… the United States must hold themselves at liberty to increase their naval armament upon the [Great] [L]akes, if they shall find that proceeding necessary.” Though shrouded in a legal tone, Lincoln’s message was clear: the attacks from Canada had to stop within six months or warships from the United States Navy would enter the Great Lakes, their cannons pointing across the border.[18]

Of course, the war ended before that six month ultimatum came to fruition. The collapsing Confederacy could no longer support raids like St. Albans anyways; the only thing that came close was an abysmal failure in November, 1864, where some Confederate agents tried to burn New York City.

Through a series of trials in Montreal the raiders were found innocent and released. The extradition trial’s ending in December, 1864 was followed by others, the last culminating in April, 1865. The prisoners were found innocent and quietly released. No one ever served jail time for the raiding of St. Albans, or the killing of Elinus J. Morrison. As a type of repayment, the Canadian government did however give a total of $70,000 to the St. Albans banks, less than half of the original amount stolen.[19] The leader of the raid, Benett H. Young, died in 1919.

Today there is a small placard in St. Albans, detailing the raid of October 19, 1864. Though usually forgotten or overlooked, the St. Albans Raid has the distinction of being the northern-most action from the American Civil War. [EDITOR’S NOTE: Click here to read about Chris Mackowski’s visit to the town, posted two years ago.]

______________________________________________________________

[1] James David Horan, Confederate Agent: A Discovery in History (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc, 1954), 168.

[2] For details on Morgan’s Raid, with Young mentioned throughout, see Betty J. Gorin, “Morgan is Coming!” Confederate Raiders in the Heartland of Kentucky (Louisville: Harmony House Publishers, 2006).

[3] Cathryn J. Prince, Burn the Town and Sack the Banks! Confederates Attack Vermont! (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2006), 123.

[4] London Gazette, May 14, 1861.

[5] Prince, 137.

[6] Horan, 170. Some of the simpler things that Horan gets wrong: “The next day [Oct. 19] was bright and clear.” It had poured rain furiously the night before and the clouds had not yet cleared. A present-day author describes the day as a “dull, bone-chilling day.” Prince, 3.

[7] Prince, 126.

[8] L.N. Benjamin, The St. Albans Raid (Montreal: John Lovell, 1865), 25. http://books.google.com/books?id=Js78I9m7Pr4C&pg=PP1&lpg=PP1&dq=l.n.+benjamin+st.+albans+raid&source=bl&ots=OfNsWaXY2U&sig=ggNMgGIQke758PgLGnXjf4h7iqc&hl=en&sa=X&ei=lGQ9VNyLFYTR8AGJ2ICQBw&ved=0CD0Q6AEwBw#v=onepage&q&f=false

[9] Ibid, 143.

[10] Jeffry D. Wert, From Winchester to Cedar Creek: The Shenandoah Campaign of 1864 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987), 229.

[11] Russ A. Pritchard Jr, Raiders of the Civil War: Untold Stories of Actions Behind the Lines (The Lyons Press, 2005), 96.

[12] Prince, 157.

[13] Benjamin, 85.

[14] Amanda Foreman, A World on Fire: Britain’s Crucial Role in the American Civil War (New York: Random House, 2010), 698.

[15] Prince, 163.

[16] Foreman, 699.

[17] Ibid, 721.

[18] The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 8, 141. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln8/1:298?rgn=div1;submit=Go;subview=detail;type=simple;view=fulltext;q1=St.+Albans

[19] Prince, 230.

The St. Albans raid was not the most northern action of the Civil War. On June 28, 1865, CSS Shenandoah captured 11 Yankee whalers in the Bering Straits, both the most northern and the last action of the war. Ironically, the Shenandoah was commissioned at Madeira in the North Atlantic on 19 October 1864 at about the same time as the Battle of Cedar Creek. So, the day that lost one Shenandoah to the Confederacy saw the birth of another.