The Strategic Impact of the Battle of Nashville

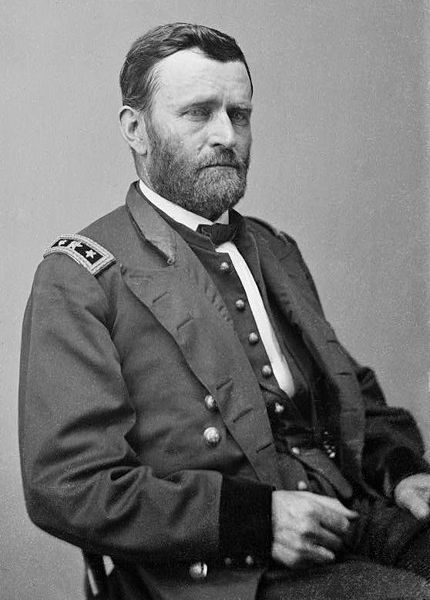

When Maj. Gen. George Thomas’ Union forces drove the Army of Tennessee from their position south of Nashville on December 16, 1864, it signaled an end to John Bell Hood’s invasion of Tennessee. Hood’s army in shambles, any hopes of Hood continuing his march beyond and into Kentucky lay dashed on the battlefield. Thomas’ resounding victory not only had resounding consequences in Tennessee, but reached farther east into Washington, D.C., Virginia and Georgia. In fact, there were two men specifically who had been keeping a close eye on the actions at Nashville: Lieut. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman.

Hood’s army had always held the attention of Grant. His operations in North Georgia in the autumn of 1864 had so occupied Grant, that he initially balked at the idea of allowing Sherman to march from Atlanta to the Atlantic Coast. In order to mollify his friend, Sherman had detached Union troops under Maj. Gens. George Thomas and John Schofield to Tennessee to deal with Hood’s imminent invasion. This action seemed to assuage Grant’s worries and he finally gave Sherman permission to proceed on his famous “March to the Sea”.

With Sherman nearing Savannah in early December, the two officers reopened communication. Not surprisingly, one of their main topics of discussion was Hood’s army. Despite sustaining devastating casualties at the Battle of Franklin in late November, Hood refused to abandon Tennessee and had continued his march to the gates of Nashville.

On December 3, Grant penned a letter to Sherman. Part of it included an update on the situation in Tennessee. “Thomas has got back into the defenses of Nashville, with Hood close upon him…part of this falling back was undoubtedly necessary…it did not look so, however, to me. In my opinion, Thomas far outnumbers Hood in infantry”.

Three days later, Grant again wrote to Sherman. This time, he laid out a plan for Sherman. “I have concluded that the most important operation toward closing out the rebellion will be to close out Lee and his army…My idea now is that you establish a base on the sea-coast…with the balance of your command come here by water with all dispatch.” Grant then disclosed his motivation for this new plan. “Hood has Thomas close to Nashville. I have said all I can to force him to attack, without giving the positive order until to-day. To-day, however, I could stand it no longer, and gave the order without any reserve.”

It was clear that Hood and his Army of Tenessee was in the forefront of Grant’s mind. So much, that he was proposing a massive undertaking. It would be no small feat indeed coordinating the sea transport of the bulk of Sherman’s 60,000 men from Savannah, along the Atlantic Coast in the middle of December to join Grant at Petersburg. Clearly, Grant felt that Thomas would attack and thus, to him drastic measures had to be taken. Grant believed it was up to him to strike a crippling blow to Robert E. Lee. As Lee’s army was the heart of the Confederacy, any success Grant could achieve with Sherman’s forces would far outweigh any consequences derived from Thomas’ lack of action or at worst, possible defeat.

These letters did not reach Sherman until December 14. He would respond two days later, telling Grant “I have initiated measures looking principally to coming to you with fifty or sixty thousand infantry”. Sherman, however, did not seem anxious to make the trip to Virginia by sea. On the evening of December 18, Sherman hinted at his true intentions, writing to Grant that “at some future time, if not now, we can punish South Carolina as she deserves…I do sincerely believe that the whole of the United States…would rejoice to have this army turned loose on South Carolina, to devastate that State in the manner we have done in Georgia, and it would have a direct and immediate bearing on your campaign in Virginia.”

These differences of opinion would be overcome by events. In a two day battle, beginning on December 15, Thomas came out of his Nashville defenses and summarily defeated Hood. When Grant received news of this victory, his entire strategic outlook changed. The same day Sherman expressed his desire to march into South Carolina, Grant wrote him “I did think the best thing to do was to bring the greater part of your army here and wipe out Lee. The turn affairs now seem to be taking has shaken me in that opinion. I doubt whether you may not accomplish more toward that result where you are than if brought here…I want to get your views about what ought to be done”.

On Christmas Eve, 150 years ago today, with Grant’s letter of December 18 in hand, Sherman penned a response. “I am pleased…you have modified your former orders…I feel whatever as to our future plans…I left Augusta untouched on purpose, because the enemy will be in doubt as to my objective point, after we cross the Savannah River, whether it be Augusta or Charleston…I will then move either on Branchville or Columbia…then ignoring Charleston and Augusta both, I would occupy Columbia and Camden, pausing there long enough to observe the effect. I would then strike for the Charleston & Wilmington Railroad, somewhere between the Santee and Cape Fear Rivers…I would then favor a movement direct on Raleigh. The game is then up with Lee, unless he comes out of Richmond…now that Hood is used up by Thomas, I feel disposed to bring the matter to an issue as quick as possible.”

While awaiting Grant’s response, Sherman attended services at St. John’s Episcopal Church on Christmas Day and that night, hosted a Christmas dinner for his subordinates. Two days later, Grant wrote back, giving his approval for Sherman to march through the Carolinas.

Although fought in Tennessee, George Thomas’ victory at Nashville completely changed the strategic landscape in the East. The defeat of John Bell Hood altered the plans of Ulysses S. Grant and freed Sherman’s armies to march north overland from Savannah. Delayed by harsh weather, on February 1, 1865, Sherman struck out from Savannah. In his wake, he would leave a path of devastation greater than what was reaped in Georgia.

Really great insights here, Dan. Thanks for sharing.