Kit Carson’s Civil War: Learning to Command, Administration and Training

Today, we are pleased to welcome guest author Ray Shortridge.

Part one in a series.

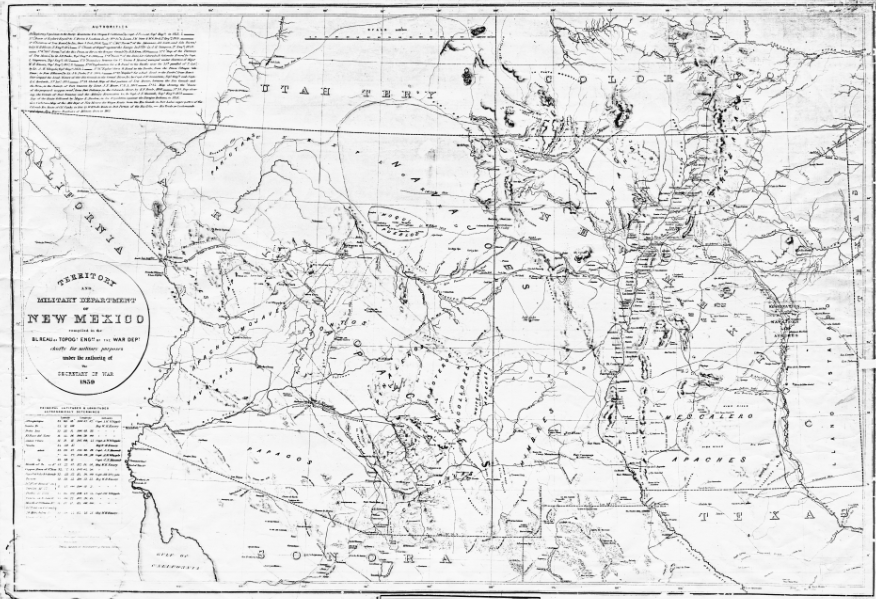

In early July, 1861, Henry Hopkins Sibley met with Jefferson Davis in Richmond. He had resigned from the United States Army while serving as a major in New Mexico Territory. Sibley proposed a campaign to conquer what is now New Mexico, Arizona, California, Colorado, and the northern Mexico states of Chihuahua and Sonora. Only a few regiments of U. S. troops and a handful of Mexican units patrolled this vast region. Davis did not document the meeting nor record his thoughts about the risks and benefits of the mission. Perhaps, because it was an easy decision — hazarding a battalion of about three thousand Texans in return for a vast southwestern empire. Davis authorized Sibley to raise three regiments of mounted infantry in Texas and lead them on an invasion of New Mexico Territory.[1]

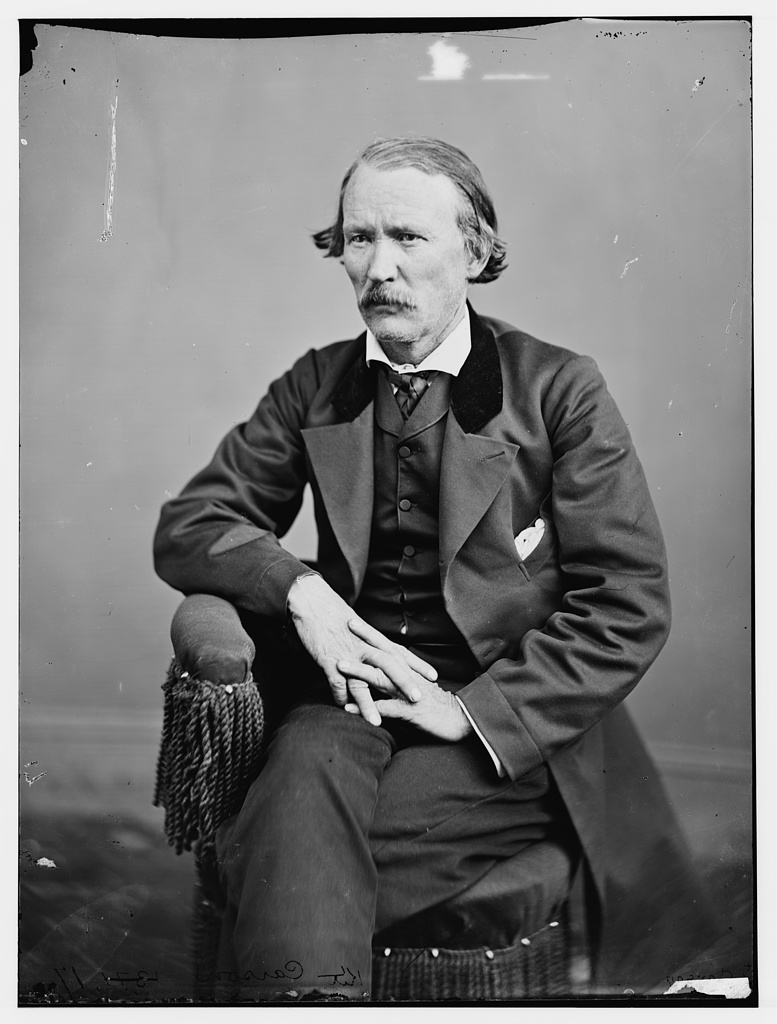

In New Mexico, the United States Army commander, Colonel Edward R. S. Canby got wind that Sibley was recruiting troops in San Antonio, Texas, for the invasion.[2] He ordered the civilian territorial governor to call for volunteers to fight the Confederates. Among the first to step forward was Christopher (Kit) Carson.

Carson was a renowned figure in New Mexico Territory. Over the years, he was a friend to territorial governors, army commanders, merchants, and ranchers. Carson was also widely known to the American public as a mountain man and explorer through John C. Fremont’s writings, pulp novels of the “blood and thunder” genre, and an as-told-to autobiography.

The governor knew that Carson had military experience. In the 1840’s, Carson had served as an army scout under Fremont and, later, General Stephen Kearny. He appointed Carson the Lieutenant Colonel of the First New Mexico Volunteer Infantry Regiment. When, on September 21, the regiment’s colonel resigned, Carson assumed full command. This would be Carson’s first experience as a unit commander, faced with its organizational, administrative, tactical, and leadership responsibilities.

After a few weeks scouting for Texan invaders near Fort Union in northeast New Mexico, Carson moved to Albuquerque where he began learning his trade as a commander. He organized the gathering volunteers into eight companies. Much of the work of a regimental commander entailed writing and reading the myriads of reports written to or by a commanding officer – commissary supplies, quartermaster inventories, daily unit strength rosters, orders, and operating procedures. This administrative side of command posed a problem for Carson, who was largely illiterate.

The story was told that a few of his men once duped him into signing a commissary requisition for what they said were kegs of molasses. Later, when he found them drunk, he found that the requisition actually was for kegs of whiskey.[3] Carson’s solution was to rely upon the regiment’s adjutant to draft the orders that he issued and review the paperwork intended for his eyes.

As the commander, Carson was responsible for instilling unit discipline and morale. This offered to be a difficult task. Regular army officers, such as Canby, felt that New Mexicans would not stand against the Texans.[4] Carson co-signed a letter stating “that without the support and protection of the Regular Army of the United States they [New Mexicans] are entirely unable to protect the public property in the Territory or the lives of such officers, civil and military, as may be left among them after the withdrawal of the regular forces…”[5]

Despite the attitude of the New Mexicans, Carson established a higher level of morale in his command than was exhibited by the other three volunteer regiments. As an illustration, pay for the volunteers was delayed, and Canby worried that going without pay would produce “a marked and pernicious influence upon these ignorant and impulsive people.”[6] Indeed, two of the companies in the Second New Mexico Regiment rebelled because “they have not been paid and clothed as they were promised.”[7] However, Carson maintained control of his men, and his First New Mexico Regiment did not mutiny.

Throughout his life, Carson never shirked a fight.[8] In August, 1861, when he heard rumors that the Confederates were approaching Fort Union, his first reaction was to go after them. “Col. Carson thinks if the Texans are coming he can collect in a few days Mexicans and Ute Indians sufficient to steal all their animals before they reach here.”[9]

In January, 1862, Canby consolidated most of his regular infantry and New Mexico volunteer regiments at Fort Craig, his southern bastion. He ordered Carson to march his First New Mexico regiment the one hundred and twenty miles south from Albuquerque to the fort.

Canby noticed that Carson instilled this aggressiveness in his command. He relied on Carson’s regiment while maneuvering against the Texans near Fort Craig. Canby ordered Carson to cross the Rio Grande River and occupy a position that was the extreme left flank of the Union line. After a skirmish with the invaders, Canby withdrew other New Mexican units and his regulars to the fort and assigned Carson and his regiment to hold the exposed position until the Texans had marched further north.[10]

After six months in command of the First New Mexico Volunteers, Carson had learned key aspects of being a commander. He capably administered his regiment and instilled high morale in his men. Canby recognized Carson’s capabilities and, when he followed the Texans north up the Rio Grande Valley, he placed Carson in command of Fort Craig.

[1] For a thorough exploration of the background of Davis’s decision, see: Charles S. Walker, “Causes of the Confederate Invasion of New Mexico,” Mexico Historical Review, Volume viii, 1933, April #2, 76-97.

[2] Canby’s immediate predecessors, Colonel Thomas Fauntleroy and Colonel William Loring resigned in order to serve the Confederacy, as did other officers, including James Longstreet and Richard Ewell. Canby and Sibley had been classmates at West Point, and Canby served as best man at Sibley’s wedding. Canby and Sibley’s wives were cousins.

[3] Hampton Sides, Blood and Thunder, The epic Story of Kit Carson and the Conquest of the American West, (New York, NY, 2006). 345.

[4] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 Volumes, (Washington, D.C., 1880-1901). Series I, [hereinafter noted as OR] Vol. IV. Chap. 11, 65, 66.

[5] Ibid.

[6] OR, Vol. IV, Chap. 11, 85.

[7] OR, Vol. IV. Chap. 11, 86.

[8] See: Sides, Blood and Thunder.

[9] Wilson, When the Texans Came, Chapman, 67.

[10] John Taylor, Bloody Valverde, A Civil War Battle on the Rio Grande, February 21, 1862, (Albuquerque, N.M., 1995), 33-38.

Interesting article; thank you.