The Capture of Jefferson Davis, part one

Part one in a series

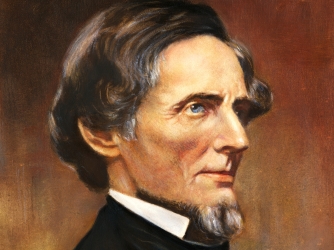

In April 1865 the very air was alive with rumors. Lee and Johnston had surrendered, and despite the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, the Southern Confederacy seemed to be going up the spout. But high profile Confederates were still at large – President Davis and his cabinet, among others. By mid-April the ambulatory Confederate Government (or what was left of it, anyway) managed to reach Greensboro, North Carolina, via what was left of the southern railroads. Davis’s objective was to flee to some place beyond the immediate grasp of the Federal armies, there to rally the South continue the fight. To do that he needed to reach either Florida, from where he could perhaps find a ship, or travel overland to Texas.

It was at Greensboro that Davis learned the full details of Appomattox, given in a personal letter from Robert E. Lee, the reading of which left Davis weeping in near-despair. The resultant consultations with his cabinet and his remaining generals revealed that virtually everyone counseled surrender. Davis refused to consider that opiton. Clinging to the last of his hopes, he would press on southward.

Accordingly, Davis headed to Charlotte in a makeshift convoy of wagons and ambulances, some of which included the Confederate treasury, much of it in gold. He arrived at that place on April 19th. The townsfolk greeted him with decidedly limited enthusiasm. Just across the Catawba River to the west, Union General George Stoneman’s Cavalry rampaged, and Federals were momentarily expected in town. Some of Charlotte’s residents expected a fearsome retaliation visited upon them should the Yankees descend on the city and discover them to be harboring Jeff Davis.

That fear proved unfounded, for that very day, the Federals turned back westward. For now, Charlotte was beyond their grasp. With this reprieve, Davis remained in Charlotte six days, struggling to remain optimistic. At one point, he insisted to his fellows that “the cause is not yet dead, and only show by your determination and fortitude that you are willing to suffer yet longer, and we may still hope for success.” Almost no one shared this belief. Then came the next blow: a telegram from Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge informing Davis of Lincoln’s assassination. What vengeance would the Unionists wreak for that act?

On April 26th, Davis left Charlotte, immediately after a gloomy cabinet meeting that discussed Johnson’s surrender to Sherman. His spirits were now very low, as outlined in a letter to his wife Varina that he wrote that day and sent southward in the hands of his personal secretary, Burton Harrison. (Varina Davis and their children had gone on ahead; Davis had not seen them since they left Richmond on March 30th.) His generals had failed him, lamented Davis, and the troops were deserting in droves. Lawless ex-soldiers pillaged the region. Still, Davis thought that if he could get to Georgia, and from there, via Alabama and Mississippi reach Texas, he might rally the deteriorating Confederacy for one supreme effort. More realistically, he also began assembling a dossier that might be useful in his defense should he be captured and survive to be tried for treason.

For Davis, any successful escape meant traversing Georgia, a risky prospect. Union Major General James H. Wilson and roughly 13,500 Federal cavalrymen occupied Macon, perfectly positioned to patrol southeast Georgia. Union commanders across the south had been alerted to watch for Davis’s passage, but Wilson’s men were the most likely to run him to ground.

But what Wilson needed was hard information, not rumor. Accordingly, when First Lieutenant Joseph A. O. Yeoman of the 1st Ohio Cavalry came to him on April 28th, proposing a daring scheme, Wilson was inclined to listen. Yeoman wanted to take about 20 men, don Confederate gear, and try and infiltrate the Rebel forces then still active in the Carolinas, in hopes of locating Davis. Wilson agreed to the plan, though it entailed considerable risk for Yeoman and his band of spies. Wilson set patrols in motion to the east and southeast, mainly towards the South Carolina border. Yeoman’s column would be ready to depart Macon at 4:00 p.m. on May 3rd.

Meanwhile, Davis reached Abbeville South Carolina, on May 2nd. Abbeville lay 30 miles short of the Georgia border – the Savannah River – and about 70 miles north of Augusta. Here Davis convened an extraordinary meeting. It was not a cabinet meeting per se, more of a council of war. The attendees were all soldiers. Present were Secretary of War and Major General John C. Breckinridge (who had caught up to the fleeing column) commanding Davis’s escort, 3,000 strong; General Braxton Bragg, the President’s military advisor; and the various brigade commanders that comprised Davis’s military escort: Brigadier Generals Basil W. Duke, Samuel W. Ferguson, John C. Vaughn, George Dibrell, and Colonel William C. P. Breckinridge.

After some discussion, Davis made a startling proposal. He would use Breckinridge’s 3,000 troopers as a “nucleus around which the whole people will rally when the present panic has passed away.” The idea was met, according to Davis biographer William C. Davis, “with dumbfounded . . . silence.” Colonel William Breckinridge (a cousin of the general’s) asserted flatly that “there was no war to continue.” Surprised, Davis then asked why these last few troops were still with him. “[S]olely to ensure his safe escape,” came the disheartening reply. That accomplished, the troops would then disperse for home. No one was willing to continue the war, especially in the form of a destructive guerrilla conflict. The South was ravaged enough without that. John C. Breckinridge and Bragg, adversaries in the past, remained silent while the junior officers spoke. Now they both endorsed their subordinates. The officers would get Davis out of the country if they could, but that would be the extent of their mission.

Here, on the 2nd of May, 1865, the Confederacy truly breathed its last. Nerve twitches at the extremities might give false hope for a few weeks more, but when these men rejected Davis’s desperate scheme, the dream was no more.

That same day, in Washington D.C., newly sworn United States President Andrew Johnson placed a 100,000 dollar bounty on Davis’s head, for supposed complicity in Lincoln’s murder. Federal troops stepped up their search with a sense of renewed urgency.

The presidential column left Abbeville that night, headed for Washington Georgia. The group was now considerably smaller. Only about 1,500 of the cavalry volunteered to continue onward. The others began their long journey homeward. Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin also left the convoy at this time, headed for Cuba, ostensibly in order to continue diplomatic efforts on the South’s behalf and promising to meet Davis in Texas. In reality, Benjamin, who knew a sinking vessel and an obsessed captain when he saw them, confided to Confederate Postmaster General John H. Reagan that he “he was going to the farthest place from the United States . . . if it takes me to the middle of China. Benjamin had no intention of going down with this ship.

(Click on map to open: Davis’s route is shown in pink, the 1st Wisconsin, in blue, and the 4th Michigan, in green. Named towns are highlighted in yellow)

At Washington, Davis learned that his family was close. Burton Harrison, escorting his wife and children, had been there only hours before. The Confederate President now decided to jettison the rest of the government, traveling on with some of his immediate staff and only ten picked troopers. Most of the treasury had already been divided, either for safekeeping or to pay off departing soldiers; now Davis instructed the remainder to be divided among the last of the 1,500 cavalry who stayed with him after Abbeville. Another cabinet member, Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory, also broke away to seek other means of escape.

Departing late in the day on May 4 and again riding through the night, by the evening of the 5th the small party traveled another 50 miles, halting at Sandersville Georgia. Here Davis learned of “parties of bushwackers” (not to mention Wilson’s patrols) out searching for a small convoy of vehicles that Davis knew to be Harrison and his family. After a short night’s rest, Davis rode hard through May 6th, hoping to catch up to Varina, his world now shrinking to concern for his family. He found them a couple of hours before dawn on the 7th.

After leaving Macon on the afternoon of the 3rd, headed northeast, Lieutenant Yeoman reached the small town of Greensboro Georgia (30 miles east of Washington) at dawn on the 5th. He now began to run into parties of Rebel cavalrymen, most of them from the force dispersed at Abbeville. Among them were some Texans, and best of all, two talkative Tennesseans from Dibrell’s Brigade. Yeoman pressed them for Davis’s whereabouts, pretending to be an officer of the Confederate 8th Kentucky bearing urgent dispatches for the C. S. President. Davis had been in Washington as of yesterday; “they had seen him themselves,” and furthermore, the pair confirmed the presence of the treasury wagons. “The troops had been given two months’ pay in coin, and they showed me $26 each which they had received.”

Yeoman immediately dispatched two couriers with this news back towards Federal lines. Within 24 hours they reached Atlanta, where their information was at once telegraphed to Wilson at Macon.

In response, on May 6, Brigadier General John G. Croxton summoned Lieutenant Colonel Henry Harnden of the 1st Wisconsin (pictured here) to headquarters. Per Wilson’s orders, Harnden was to take 150 of his men on a patrol to the southeast, ranging between the Ocmulgee and Oconee Rivers, seeking Davis’s group. The Rebel party was rumored to be 600 or 700 strong. When Harnden balked at this numerical disparity, Croxton reassured him that, according to the latest (Yeoman’s) intelligence, the men escorting Davis were “greatly demoralized,” that “many were leaving him; they would be poorly armed, and it was doubtful that they would fight at all.” Besides, Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin D. Pritchard would be leading his own 4th Michigan Cavalry, 300 strong, on a similar scout along the west bank of the Ocmulgee; they could provide support if any were needed. Harnden’s patrol departed on the afternoon of the 6th, Pritchard’s at dawn on May 7th.

In response, on May 6, Brigadier General John G. Croxton summoned Lieutenant Colonel Henry Harnden of the 1st Wisconsin (pictured here) to headquarters. Per Wilson’s orders, Harnden was to take 150 of his men on a patrol to the southeast, ranging between the Ocmulgee and Oconee Rivers, seeking Davis’s group. The Rebel party was rumored to be 600 or 700 strong. When Harnden balked at this numerical disparity, Croxton reassured him that, according to the latest (Yeoman’s) intelligence, the men escorting Davis were “greatly demoralized,” that “many were leaving him; they would be poorly armed, and it was doubtful that they would fight at all.” Besides, Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin D. Pritchard would be leading his own 4th Michigan Cavalry, 300 strong, on a similar scout along the west bank of the Ocmulgee; they could provide support if any were needed. Harnden’s patrol departed on the afternoon of the 6th, Pritchard’s at dawn on May 7th.

Davis’s reunion with Varina on the morning of the 7th proved bittersweet. While happy to see him, she also immediately urged him to leave her and the children again, knowing he could make better time on horseback. She iwas also full of scorn for the locals, telling him angrily that “this people are a craven set. They cannot bear the tug of war.”

Now began a strange slow-motion odyssey. Davis did leave Varina’s little wagon convoy behind, but May 8 proved stormy, and the presidential party’s horses were nearly played out from nearly non-stop riding over the past few days. Davis made so little progress that Varina’s wagon column caught up with him that evening at the ferry across the Ocmulgee near Abbeville Georgia (not to be confused with the other Abbeville) where they found the president asleep on the floor of a deserted house. Despite violent thunderstorms, Davis told Harrison to keep the wagons moving through the night; he and his men would catch up in the morning. True to his word, Davis rejoined the family convoy before noon on the 8th; the whole group then pressing on to Irwinville, halting just outside that hamlet at about 5:00 p.m.

The 1st Wisconsin Cavalry reached the town of Dublin, Georgia, on the afternoon of the 7th, after nearly 24 hours in the saddle. Colonel Harnden found both the town and the surrounding countryside to aswarm with recently paroled Rebels, all claiming to be from Johnston’s army, headed home after the surrender. The sudden appearance of Federal cavalry left everyone agitated, noted Harnden, but no one was willing to talk about Davis. No white person, at least. In the night, Harnden’s body servant Bill, (who had once belonged to an officer on Bragg’s staff) wakened the Colonel with important news. A local Negro informed Bill that Davis had been seen in town along with his wife, having crossed the Oconee River at the Dublin Ferry just that morning.

Harnden had already detached 30 men to watch an important crossroads behind him. Now he further divided his force, leaving 45 men to watch Dublin and the ferry there, and immediately rode on after Davis with his remaining 75 troopers. Despite May 8th’s driving rains, Harnden doggedly pressed on, questioning locals, tracking the wagons by their ruts where he could, and struggling through rain-choked swamps. Fearful of losing what little trail he could see, however, with the coming of full darkness the colonel called a halt for the night.

Harnden and his men were back in the saddle again at first light on May 9. The Wisconsin cavalry also crossed the Ocmulgee at Abbeville, and, with the reluctant aid of a local guide, made for the reported campsite of an unknown party near Irwinville. Before they reached that location, however, Harnden encountered four troopers from the 4th Michigan Cavalry who took him to Colonel Pritchard. The two commanders compared notes. Pritchard had been patrolling towards Abbeville, trying to intercept any party that crossed the river, but so far he had heard nothing concrete concerning Davis’s whereabouts. Harnden gave Pritchard all the information he had, describing the trailing of the wagon group for some miles. Even if Mr. Davis was not with the wagons, Harnden opined, he expected the Confederate president to meet up with them eventually. With that, the two patrols each continued on with their assigned missions.

to be continued…

Sad I am as I read this. This web site has been wonderful for me.

CSA Captain Given Campbell of Paducah Ky was chosen to lead a small unit of W/Ky men that guarded and escorted Jeff Davis on the flight from Richmond. Campbell and mostof his men were captured 5-10-1865 with the Davis party near Irwinsville Ga. Have found the burial sites of most of the men that were with Davis on -10-1865.

Talley Bailey, Just saw your older post about CSA Capt. Given Campbell’s capture with Jeff Davis. I am trying to find out which U.S. cav. unit captured Lt. Col. Edward A. Palfrey, CSA Ass’t Adjutant General, CSA War Dept. who had been with the Davis party.

Col. Palfrey was captured near Athens, GA. There might have been a Lt. Col. John Withers from the War Dept. with him. Thank you!

Talley Bailey, any knowledge of the Union soldiers names that escorted Jeff. Davis to act. Monroe in 1862?

That should say ‘Fort Monroe’. I have a pistol that was carried by one of 6(?) Union soldiers who escorted Davis. Love to know any info or Professors to contact on this.

M.G.

Brigadier (later Major) General John Croxton’s middle name was Thomas. He commanded the First Brigade of the First Division (McCook) or Wilson’s Cavalry Corps.

My Great Great Grandfather Jacob Gosh 1st Infantry- Hull, WI Portage County helped capture Jefferson Davis.

1 st Calvary

It is possible Philip Biesanz, a private in Company C, 5th Regiment of Iowa Cavalry, was one of 4 escorts to accompany Jefferson Davis from the place of his capture to Washington. Cheryl