“The nearest run thing you ever saw in your life”: The 200th Anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo

Though our main focus here at ECW is the American Civil War, we would be remiss to fail noting the 200th Anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo.

Following Napoleon’s abdication in 1814, the rest of Europe thought that the nightmarish wars were finally over, having killed millions and leaving even more destitute. That relief was short-lived however, with Napoleon escaping from his exile on Elba and returning to the shores of France in March, 1815. The Grande Army reformed and King Louis XVIII fled his recently-claimed throne.

On June 15, 1815, French forces crossed the border into Belgium and began moving in mass towards Brussels. The Duke of Wellington, Arthur Wellesley, found out about the invasion that night at a grand ball and quickly left to mobilize his own forces, a hodge-podge of allies. He was joined by the Prussians, commanded by Field Marshall von Blücher.

June 16 saw the campaign’s first pitched battles, with the British and their allies fighting against detached elements of Napoleon’s command at Quatre Bras, while the former Emperor himself won his last battlefield victory, against the Prussians, at Ligny.

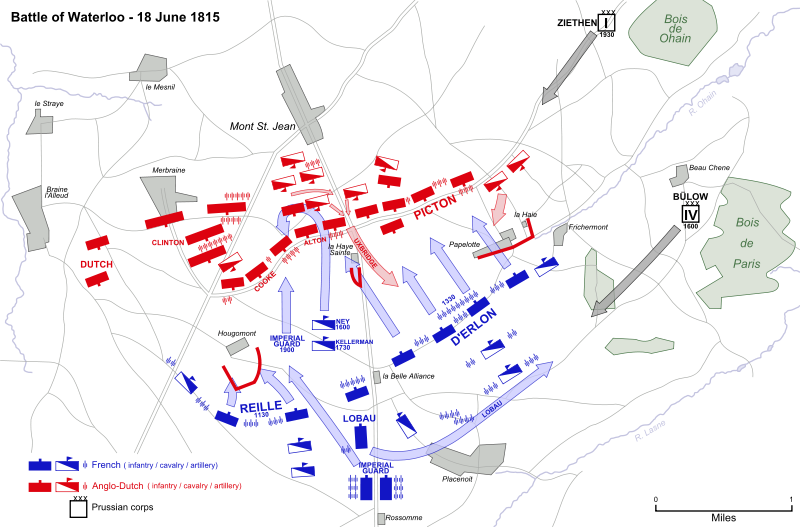

The tumultuous days in mid-June reached its zenith today, June 18. With the Prussians forced back at Ligny, Wellington faced the daunting task of fighting Napoleon’s legions alone for the most of the day, at least until Blücher could turn his men around and march to the sound of the cannons.

Over the course of the day places like the Château d’Hougoumont, La Haye Sainte, and the main Allied line along a ridge were pounded by various French assaults. Napoleon’s cannon blasted away at the Allies, and Wellington’s men took cover behind the reverse slope of their ridge. Wellington quipped, “Hard pounding this, gentlemen; let’s see who will pound longest.”

When it appeared through the smoky confusion that Wellington’s men were falling back, tens of thousands of French cavalrymen charged their mounts up the ridge, thinking the day was won. Instead, as they crested the ridge, they met bayonet-tipped infantry squares; solid masses of infantry ready to blast the heart out of any attack. Over and over again the French squadrons wheeled into position, and over and over again the Allies shot them to pieces.

The constant pressure was weakening Wellington’s line, however. La Haye Sainte fell to repeated attacks, and Hougoumont barely held, though burned to a shell of itself. “Give me night,” Wellington worriedly said, “or give me Blücher.”

Before either came, though, came Napoleon’s hell-for-bent effort on piercing the Allied line; he sent in the Old Guard. Though irreversibly damaged in the infamous 1812 campaign against Russia, the Old Guard still remained Napoleon’s shock troops. They advanced steadily up the ridge, crying out at each step “Long live the Emperor!” The French columns violently slammed into the Allied line, held at the most dangerous point by the British Foot Guards. Redcoat Guards rose to their feet and met the Old Guard with repeated volleys that churned the French assault columns into charnel houses. And as the Old Guard began to break, Blücher arrived.

Eager Prussians poured into Napoleon’s right flank around the village of Plancenoit, routing the French forces that tried desperately to stem the tide. And as dusk came to the battlefield at Waterloo, Wellington signaled a general advance, sending his begrimed and bloodied forces after Napoleon’s men, routing them from the field.

There were other battles following Waterloo, mainly Wavre, which continued into June 19, but Napoleon’s hopes for re-establishing his Empire was torn to shreds on the battlefield on June 18. The day left close to 60,000 killed and wounded on both sides; casualties approaching that magnitude would not be seen again on a battlefield until the American Civil War.

Napoleon, defeated, was sent into exile again— to Saint Helena in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. This time there would be no escape. He died there in 1821.

For Wellington, Waterloo left him a victor, but barely. He told one that the battle was “the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life.” Then, adding to another, Wellington wrote that “nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won.”

Waterloo is considered one of the most decisive battlefields in World history. Relating to the Civil War, generals were intimately familiar with Napoleon, Wellington, and the campaign. George B. McClellan in his campaigns seemed to always plan for his own Waterloo masterpiece, ironic considering his nickname of the “Young Napoleon.” And Alexander Webb, commanding the Philadelphia Brigade at Gettysburg at the height of the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble Attack on July 3, later said that “Gettysburg… was, and is now throughout the world known to be the Waterloo of the Rebellion.”

In the end, however, it matters most on this bicentennial to remember those who fought and died on a muddy battlefield just south of Brussels.

Thanks Ryan Quint for your post. As an obscure sidelight to this post, I had opportunity to “venerate” Napoleon’s gallstones which are in a medical museum in London. I don’t have details on Napoloeon’s autopsy and how they happened to be in that museum but, I pass this along as a minor footnote!

F. Norman Vickers, M. D.,

Pensacola, FL

Did not know about that Webb quote. I get the same feeling of sublime importance at both the Angle and where Wellington’s Guards repelled the Garde Imperiale.

Awesome article! So glad someone else is writing / sharing about Waterloo. Great comparison to Gettysburg at the end – that is something I’ve been studying in the last few weeks.

This post made me very happy because most of the folks have gone running the opposite direction when I mentioned the battle, so it was a pleasant surprise to find the article and one of my all-time favorite battlefield paintings in my WordPress Reader this evening. Thank you, thank you!

The more I read about Waterloo (which, admittedly, isn’t much so far), the less I am overjoyed at its outcome. Napoleon and the French people in 1815 were exhausted; even if they’d won, Britain and its continental allies could probably have contained France. What did all that bloodshed (mainly by common people who suffered for their rulers’ vanities) achieve? Britain’s freedom to build a huge empire? Maybe that’s just the American in me talking.

And Wellington was an arrogant jerk.