“The General Result Was In Our Favor”: The Army of Potomac’s Victory at Antietam

Today, we are pleased to welcome guest author Kevin Pawlak

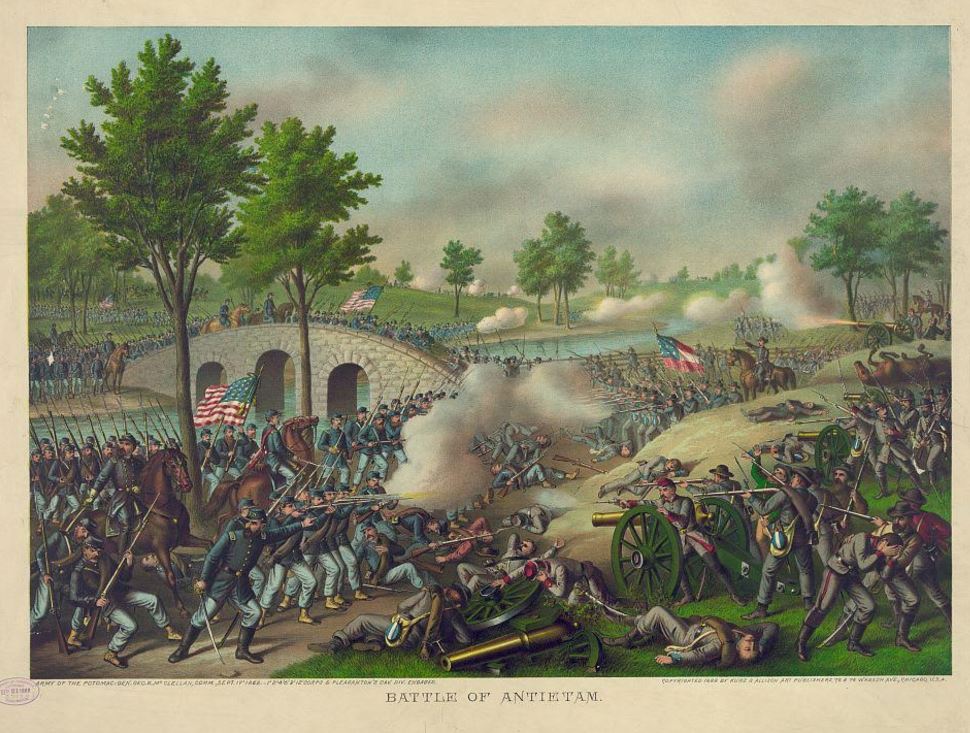

Fortunately, for the sake of debate, the outcome of Civil War battles is not as clear-cut as that of a football game, where one can look at the scoreboard at the end of the game and easily determine who won, who lost, or, in some cases, if the outcome was a draw. Historians endlessly debate whether certain battles were overwhelming victories, marginal victories, or draws. Perhaps no other battle’s tactical outcome is more misunderstood than the bloodiest single day battle of the war: Antietam.

No one would doubt Antietam’s significance in the larger picture of the war. However, the common conception of Antietam is that the battle was tactically a draw, with neither side having gained a significant enough of an advantage to have claimed the victory. This article will challenge that commonly held belief, using particular instances from the battle and the Maryland Campaign to demonstrate the Army of the Potomac’s victory at Antietam.

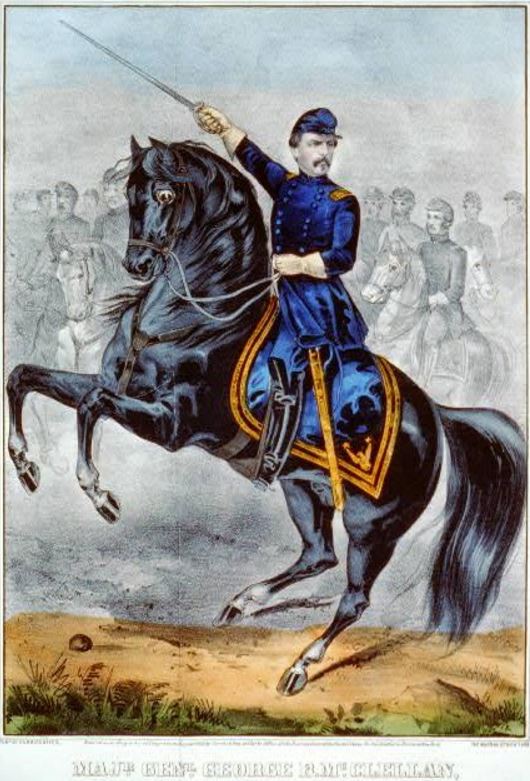

The morning following the Battle of Antietam, Major General George B. McClellan wrote his wife regarding the previous day’s action:

We fought yesterday a terrible battle against the entire rebel army. The battle continued fourteen hours and was terrific; the fighting on both sides was superb. The general result was in our favor; that is to say, we gained a great deal of ground and held it. It was a success, but whether a decided victory depends upon what occurs to-day. I hope that God has given us a great success.[1]

Most people automatically dismiss McClellan’s proclamation of marginal victory as farcical. But in order to gauge McClellan’s and the Army of the Potomac’s success at Antietam, we must go back to the day before the battle, when the Federal army gathered on the east side of Antietam Creek opposite their enemy.

Robert E. Lee and his Confederate army felt safely ensconced in their position on the west side of the Antietam. Following his defeat at South Mountain on September 14, Lee abandoned his campaign and made plans for his army to vacate Maryland. As Lee crossed the Antietam and ascended an impressive incline between the creek and Sharpsburg, his confidence began to build. News soon arrived that his divided army, now free to unite, could do just that and Lee determined to salvage his campaign. Examining the ridge he perched his men atop, Lee told his soldiers, “We will make our stand on these hills.”[2]

Much has been made of the body of water behind the Army of Northern Virginia on September 17—the Potomac River. In fact, its presence and Lee’s decision to stand and fight at Sharpsburg is one of the most criticized of his military career (Lee was not pinned directly against the river as some believe, but in fact had a series of ridges to fall back on closer to the river and also had several miles of open countryside behind his lines which he used to move his troops skillfully to threatened points of the battlefield on September 17).[3] While Lee may have momentarily considered the minor dangers of fighting with the Potomac several miles behind him, he probably did so only briefly as he looked east from his position and saw another body of water which he would usher into his defense.

Throughout the Maryland Campaign, Robert E. Lee always moved with a natural barrier between his army and the enemy. The first was the Potomac River, which Lee crossed to enter Maryland at the outset of the campaign—a time when many Federals in the area were on the south side. Next, while Lee rested his army in Frederick for several days, the Monocacy River served as a buffer between the two forces. Third, when Lee divided his army to subdue the Union garrisons in the Shenandoah Valley, he placed Catoctin and South Mountains between his separated army and McClellan’s forces. When McClellan pierced that barrier on September 14, Lee sought another barrier to shelter behind; he found Antietam Creek.

Attacking across a formidable stream like the Antietam would be no easy task and both McClellan and Lee knew that well. In his final report of the campaign, McClellan called Lee’s position atop a high ridge behind a creek “one of the strongest to be found in this region of country, which is well adapted to defensive warfare.”[4] After determining the best way to attack Lee, McClellan, the general often portrayed as one who shied from a fight, attacked despite the obvious strength of the Confederate position.

In the vicinity of what became the Antietam battlefield, there are five major crossings of the creek, named in order from north to south: the Upper Bridge, Pry’s Ford, the Middle Bridge, the Lower (Burnside) Bridge, and Snavely’s Ford. When McClellan ordered his army forward on the afternoon of September 16, 1862, only one of those crossings was securely in his hands: the Middle Bridge. Joseph Hooker’s crossing at the Pry’s Ford and Upper Bridge placed those two crossings squarely under Federal control, but Lee still held the crossings on the southern end of the field. Why did Lee cede the battlefield’s northern crossings to McClellan? The answer may never be known with certainty, but a study of Lee’s generalship throughout the campaign and war may provide a clue.

Lee’s decision to not directly defend the upper crossings may have both defensive and offensive reasons behind it. Firstly, Lee recognized the weakness of the area where his left flank would be anchored during the coming fight—its defensibility paled in comparison to that found in the center and right of Lee’s line. His left flank had to be anchored back from the creek in order to keep the road north, the Hagerstown Pike, within his control should he decide to move in that direction.[5] Additionally, by baiting the Federals to cross the creek, Lee might be able to catch it in a position where the enemy army found itself on two sides of a formidable stream, something he took advantage of several months earlier outside of Richmond and something he would try again along the banks of the North Anna River in 1864.

Robert E. Lee’s strategy on September 17 was not merely to counter the blows of the Union army but, according to some historians, Lee prepared offensive strikes meant to drive the Federals back across Antietam Creek and destroy large portions of the Army of the Potomac.[6] If those offensive strikes were successful, Lee could regain some of the upper crossings of Antietam Creek for the Army of Northern Virginia and, in turn, catch the Army of the Potomac divided by the creek with portions of that army fighting with the wide stream at its rear. Unfortunately for Lee, McClellan blunted those assaults and did not give Lee the opportunity for sweeping success he desired.

When viewing the terrain of the Antietam battlefield, George McClellan—like Lee—determined the weaker part of the line to be the northern half. Thus, he decided to open his attacks on September 17 there, using the aggressive Joseph Hooker as the tip of the spear. George McClellan never left a solid answer regarding what his plans for that day were but, based off of his two reports of the campaign, which occasionally differ, and the reports of his subordinates, a reasonable guess can be determined as to what McClellan instructed his army to do.

Despite the discrepancies between McClellan’s October 1862 and August 1863 reports, one thing seems clear: he aimed to maintain as much flexibility as possible during the fight so he could react to the flow of battle. Regardless, he plotted out his course of action and determined to first strike Lee where he believed Lee was weakest—the northern half of the battlefield. Meanwhile, Burnside would attempt to roll up the Confederate right should Hooker prove successful in drawing the enemy away from that sector of the field. McClellan believed that one or both of these attacks could be successful without drawing much from his reserves. Should he have enough reserves at the moment he felt the Confederates pressured the most, he would send them directly against the heights in his front.[7]

These attacks did not go precisely as McClellan had hoped and the ferocious fighting on September 17 forced McClellan to send his reserves away from the center of his line. Though his plan did not come to full fruition, his army had gained ground compared to what they held at the start of the fight.

Even though the ground that the Army of the Potomac had gained proved minimal in some parts of the field—approximately one-half mile in most parts—the elimination of the buffer between the two armies forced Lee’s hand: he had to seek another barrier.[8] For Lee, the only one left was the Potomac River several miles behind him. However, he could not pull out of his position immediately and had to wait until the night of September 18 to do so. Lee not being driven from the battlefield the day of the battle has, just like the argument that the Army of the Potomac gained little ground, been used by many students of the war to justify their stance that the Battle of Antietam was a drawn fight. Upon closer examination, this too falls apart.

Lee’s stand at Sharpsburg on September 18 is something visitors to Antietam battlefield sometimes equate to the southern chieftain holding his fist defiantly in the air, daring McClellan to attack him. In reality, Lee likely stood there on the 18th because, as one of the campaign’s leading historians put it, “there was good cause to believe that waiting a day could not lead to a disaster worse than attempting a hasty retreat.” No preparations had been made for a withdrawal on September 17 “and to locate the troops after the day’s confused fighting and to organize their withdrawal in darkness may have been impossible.”[9] Evidence also suggests that Lee began removing some of his important assets—particularly his wounded—to the Virginia side of the Potomac on the night of September 17, implying serious considerations of a return to Virginia as soon as it was practicable for the army to do so.[10]

George McClellan originally planned to continue the attack on September 18 but eventually decided against it before anyone moved forward. Simply put, he did not foresee any better chance at defeating the enemy thanks to what he had seen the previous day (every attack he had thrown at Lee had been equally repulsed). Additionally, the Army of the Potomac was exhausted, worn out, and bled out from corps commander to private (McClellan could count three corps commanders, four division commanders, and ten brigade commanders as casualties in the campaign as well as over 12,000 others), thus seriously diminishing the likelihood of destroying Lee’s forces if any of the troops who fought on September 17 were to be reused.

Lastly, though McClellan did have some relatively fresh troops available on September 18, those fresh troops only equaled the number of men Lee had within his entire army. Historian Joseph Harsh said it best: “There are no good grounds—even in hindsight—for believing the 24,000 men in the Fifth and Sixth Corps (including Couch) could have defeated, let alone destroyed, Lee’s 25,000.” Armchair generals love to berate McClellan for not attacking again despite these severe handicaps but always fail to recognize that he did not back down on September 18, thus “exert[ing] enough pressure” on Lee to force him to abandon his position around Sharpsburg.[11] And when Lee and his army did leave Maryland, they did so in one night; it took them three days to enter the Old Line State. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia left in a hurry.

The Army of Northern Virginia that returned to Virginia on September 18-19 was not the one Lee brought with him into Maryland just a couple of weeks earlier. Lee lost nearly 14,000 men in battle from September 5-20, and he estimated the number of stragglers who left the army’s ranks as anywhere “from a third to one-half of the original numbers” the army began the campaign with.[12] At Antietam alone, Lee lost an estimated 27.62% of his men compared to 22.16% of the Army of the Potomac.[13] The arithmetic that heavily plagued the Confederacy later in the war was already counting heavily against it.

Army of the Potomac records counted 13 guns, 39 colors, at least 15,000 small arms and 6,000 prisoners as the booty they reaped from the campaign.[14] Clearly, the Army of Northern Virginia had received a beating at the hands of George McClellan and the Federal army. One other historian studying Lee’s generalship claimed Antietam “momentarily paralyzed” the Army of Northern Virginia, which “never fully recovered” from that fight.[15]

Thus, the pounding, relentless blows that McClellan threw at Lee’s army all day on September 17 had their effect. The assaults forced the crossing of Antietam Creek, seized crucial crossing points critical to the retention of Lee’s defensive position, and ultimately forced Lee to seek another defensive barrier, which left him with no other option than to leave Maryland for the safer soil of Virginia. These assaults also did gain critical high ground on the northern end of Lee’s line all the while exacting a fearsome toll on the Confederate army, which proportionately got the worst of the fight. Lee’s army would feel that fight for a long time beyond September 17, 1862, and the misfortune and defeat that they suffered on the banks of the Antietam would leave a bad taste in their mouths for many months. Indeed, George McClellan was correct—the result of that bloody fight at Antietam was in his favor, and he had the trophies to prove it.

[1] George B. McClellan, McClellan’s Own Story (New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1887), 612.

[2] Joseph L. Harsh, Taken at the Flood: Robert E. Lee & Confederate Strategy in the Maryland Campaign of September 1862 (Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 1999), 305.

[3] Edward Porter Alexander, Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander, ed. Gary W. Gallagher (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1989), 145-46. E.P. Alexander was one of Lee’s staunchest critics regarding his decision to fight at Sharpsburg, a decision Alexander called Lee’s “greatest military blunder…”

[4] OR vol. 19, pt. 1, 54.

[5] Harsh, Taken at the Flood, 303-04.

[6] See the provocative article, Steven W. Knott, “Lee at Antietam: Strategic Imperatives, the Tyranny of Arithmetic, and a Trap Not Sprung,” Army History no. 95 (Spring 2015): 32-40, for an excellent example of this theory.

[7] OR 19, pt. 1, 30, 55.

[8] Ground gained, or lack thereof, is often used by historians as a gauge to determine the victor of Civil War battles. However, that seems negligible. Most would agree that the Battle of Gettysburg was a Union victory but Lee gained much more ground than the Union Army ever did.

[9] Harsh, Taken at the Flood, 428.

[10] Kevin R. Pawlak, Shepherdstown in the Civil War: One Vast Confederate Hospital (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2015), 87.

[11] Harsh, Taken at the Flood, 444.

[12] Joseph L. Harsh, Sounding the Shallows: A Confederate Companion for the Maryland Campaign of 1862 (Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 2000), 222; OR vol. 19, pt. 2, 606.

[13] Ezra A. Carman, The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, ed. Thomas G. Clemens, vol. 2, Antietam (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2012), 602-11.

[14] OR vol. 19, pt. 1, 33.

[15] Quoted in Alan T. Nolan, “General Lee,” in Lee the Soldier, ed. Gary W. Gallagher (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), 245.

Interesting thesis & I agree that an argument for a Federal tactical victory can be made…I do, however, believe that the author makes a better case for why McClellan should have attacked on the 18th than justifying why he did not. He had fresh troops (5th & 6th Corps) equal in strength to the entire worn out rebel army IN ADDITION TO his entire army, in no worse shape than the Rebs.

Dan,

I appreciate your comments and am glad you can see an argument being made for a Federal tactical victory. As for the second part of your comment, you are right in saying that–I just phrased that poorly, but thank you for pointing that out. You are correct that McClellan did have more men than just the 24,000 of the 5th and 6th Corps. What I did not clarify or expand upon and should have is to determine what the offensive capabilities of those troops were. While I will say that Lee was battered at Antietam and that it was a Union victory, Lee hit McClellan back just as hard as McClellan hit him. A few examples:

1. The high command of the Army of the Potomac was shot to pieces during the campaign, and could the replacement commanders have been called upon to launch more attacks the next day? Of course, in hindsight, yes. But McClellan did not think so and would not risk it, especially since he was not prone to taking major risks. From September 14-17, the Army of the Potomac had lost three corps commanders, 4 division commanders, and 10 brigade commanders. On top of that, the regimental command was in shambles. Captains commanded 20% of the army’s regiments at the end of the battle, compared to 10% at the start, while colonels commanded only 28% of the army’s regiments at the end compared to 43% at the start. Remember too, the Army of the Potomac at Antietam had only been pieced together from four separate armies and an influx of brand new recruits only two weeks before Antietam.

2. Not only was the high command of the army in shambles, but the fighting men were just as haggard, hungry, and exhausted as those of the Confederate Army. While Lee complained that perhaps anywhere from 1/3 to 1/2 of the army he entered Maryland with had straggled from the ranks by the middle of the campaign, a similar statement by McClellan would not have been far out of the ballpark. Charles Wainwright was not present on the 17th (he reached the field the day after the battle) but as he ascended South Mountain on his way to the field, he wrote this: “The whole of the way up we travelled in the middle of an army; so many men straggling forward were there that it seemed as if one-half the army must have been left behind. A number were without shoes, and a good many appeared to be really trying to get up….” Similarly, George Meade, successor to Hooker in command of the 1st Corps, noted a serious problem in straggling just 6 days after the fight. To pump up his argument and to show the serious problem of straggling which diminished the fighting capabilities of an army, Meade noted that the day after the battle, September 18, he could count 6,364 officers and men in his command. Just five days later, on September 22, the strength of his command had increased by 8,875 officers and men! How effective would some of those other corps have been in attacking again? Of course, we will never know but it all provides some excellent food for thought.

Thanks for your comments!

— Kevin

An interesting perspective. I would add that (IIRC from Harsh) Lee actually was thinking of possibly taking the offensive on September 18 and was urged to withdraw by – of all people – Stonewall. As for the statement that “George McClellan was correct—the result of that bloody fight at Antietam was in his favor, and he had the trophies to prove it”, that may be true in a sense. But that is a far cry from McClellan’s assertion that the battle was fought “brilliantly”, as he (ever the narcissist) told his wife was the view of those whose judgment he trusted. Not hardly. And I’m intrigued by Harsh’s suspect (IMHO) premise that McClellan would have had to defeat Lee’s 25,000 with only his “fresh” 24,000 (see Dan’s comment above). If we’re going to subtract everybody still standing and armed in the First, Second, Ninth, and Twelfth Corps, who on earth are we counting to come up with Lee’s strength? It seems to me that most of those fellows were from units that got battered the day before, as well. Last, are we really supposed to give Mac credit for not “backing down” on 9/18??? His opponent was down to a battered remnant of his ANV; that army had been living off the land (without complete success) for 2 weeks and more; and it had its back to a river. How McClellan should come out of this with a “medal” is beyond me.

John,

Thank you for reading the post and I appreciate your comments and feedback. Without diving into debates about McClellan’s personality, something we have a great and fortunate insight to thanks only to the publication of his letters, I’d like to offer a reply in order of the issues that you raised.

1. Regarding the issue with Harsh’s prospect of counting numbers on the 18th, to save my fingers, I’d like to refer you to my reply above to Dan’s comments.

2. In regards to giving McClellan “kudos” for not backing down on the 18th, I’d like to start by this. George Meade did not back down on July 4, 1863 nor did he attack despite numerical superiority or the fact that the argument could be made that maybe his army was in better condition than Lee’s, an assertion very difficult for us to determine even with 150+ years of hindsight. By not blinking and not moving, Meade forced Lee to make the next move which resulted in Lee’s retreat. How is McClellan not backing down on the 18th any different?

Also, McClellan had no way of knowing that Lee’s army was a “battered remnant” as many modern historians say it was. In fact, based off everything McClellan saw at Antietam on the 17th, Lee’s army still seemed very capable of powerful offensive strikes, i.e. Hood’s attack into the Cornfield, McLaws’ and Walker’s attacks in the West Woods, and A.P. Hill’s counterattack against Burnside, all of which blunted Federal offensives. If those still leave any doubt about Lee’s ability to stage a successful offensive operation despite the condition of his army, one need look no further than his attack at Shepherdstown on September 20, 1862, which despite the Union force having its back to the river (literally right to the river, whereas Lee had several miles between him and the river), it was still not even close to being destroyed.

Lastly, and this is something all people looking back at the Civil War today seriously tend to forget, is that the soldiers and generals on the ground did not know what was going to happen next. We look at battles and generals’ decisions knowing the outcome of battles. They had no idea what the enemy was going to do. Battles are not like football games where a coin toss determined who would attack and who would defend. McClellan had no idea that Lee would not try to attack him on the 18th before McClellan could prepare an offensive of his own. But what if McClellan did attack on the 18th and was similarly repulsed? His corps commanders–those left standing–warned him that another repulsed attack might spell doom for the Army of the Potomac. These men were tired and hungry and exhausted too. And if a failed Federal attack were followed up by another Confederate counterattack, much of McClellan’s army now had its back to a formidable stream and could be severely beaten in detail and lose the battle, something the United States could ill afford at that time in the war, especially.

Does McClellan deserve a medal for his victory at Antietam? Probably not a gold medal as you imply, but his conduct during the battle is commendable.

Thanks for your thoughtful reply and comment!

— Kevin

Kevin: Thanks for the response. It certainly is legitimate to point out the command losses in the A of the P from 9/14 – 9/17, but i think it’s also fair to say that two of the three corps commanders were brand new to the role – one having been in charge for only 48 hours – and in one case there was a “wing” commander extremely familiar with the corps, so it’s not nearly analogous to Meade’s losses at that level at Gettysburg (although one might quarrel about the “effects” of losing Dan Sickles). As for Mac’s conduct of the battle, the Union attack ended up being disjointed, and that on the left wing was a debacle. The tendency is to lay that at the feet of Burnside, but there was a lot of wasted time which an aggressive army commander should have used to get things rolling . I suppose that the “big picture” problem I have is that historians who try to explain/justify McClellan’s actions always find ways to credit Mac’s inflated estimates of enemy strength, etc. Full disclosure – I have little regard for McClellan as a field commander (quite the opposite when it comes to his role as a “logistician” and “chief of staff” type). I also firmly believe that his trusted Fifth Corps commander should have been cashiered – not for the trumped up charges by Pope, but for his communications with Manton Marble, which I believe were in violation of the Articles of War. “There’s Something About George…”

Small correction – I meant to say all 3 were new to the role.

Hi John,

Thanks for responding. I think it’s safe to say that you and I respectfully agree to disagree (nothing wrong with that, as history wouldn’t be so fun without debate!) but I’ll throw in my two cents here.

You are correct that 3 of McClellan’s corps commanders were new to their roles during the campaign (heck, we could even say 4 if you want to count Jacob Cox when he replaces Reno at the head of the 9th Corps). Despite their new roles as corps commanders, Reno, Mansfield, and Hooker were all well respected by McClellan and each in their own right had experience in battle and war and McClellan was clearly shaken by their loss. At 9:10 a.m. on the 17th, he sent two dispatches–one to Burnside and the other to Sumner. Of course, with both stamped at the exact same time, it’s tough to determine which was sent first but I think based off the tenor of the two, we can conjecture. McClellan first sent the note to Burnside telling him to open his attack, ending the note with the words, “all is going well.” Within an instant, a courier must have arrived from the northern end of the battlefield that told McClellan of Hooker’s wounding and Mansfield’s mortal wounding. Before telling Sumner about the wounding of the two corps commanders on that end of the field, McClellan’s tone changes dramatically and warns Sumner to advance carefully, as he feared “our right is suffering.” The knowledge of the beating the 1st and 12th Corps had taken plus the loss of each of their commanders clearly shook the commanding general. As for Reno’s loss, I won’t dive into much detail with that, but I think one of the greatest things lost in him was his staff, which accompanied the general’s body initially back to Washington. Jacob Cox did complain about not having a large enough staff for corps level work.

Regarding McClellan’s attacks, I am in full agreement with you that they were piecemeal and disjointed. Regardless though, his attacks did break Lee’s defensive barrier, one of the main reasons I consider Antietam a tactical Union victory. Part of this disjointedness, especially initially, has to lie at McClellan’s feet, other parts not. While I’ll easily admit that Burnside and Cox had the toughest task of any Union commander on the battlefield that day, the attacks that they themselves ordered were uncoordinated. You’re right, McClellan was not an aggressive general but he was no idiot either.

Lastly, full disclosure, I find Fitz John Porter fascinating but do agree with you that his letters to Marble earn him no favor points. Was he treasonous to the Union cause? Far from it, but his lack of discretion did not serve him well and for that he was canned.

Again, I think we agree to disagree, which is fine and fun, but I think discussion’s like this are always helpful and useful. Thanks for responding!

— Kevin

Kevin: To your last post – good points on “agreeing to disagree”. There’s plenty of room for debate on these issues and McClellan is a bit of a “third rail”. I think his response to Hooker’s and Mansfield’s removal can usefully be contrasted with Lee at Chancellorsville. Grievously outmanned and in an extremely dangerous tactical situation, he lost Jackson and promptly put a cavalry officer in his stead. Being a cynic, I can envision no scenario in which Mac would even have considered doing likewise (which is why I’ve always laughed at Lee’s postwar assessment of Mac as his toughest opponent). To be clear regarding our friend Porter, I’m referring to Art. 5 of the 1861 Articles of War. Pope (and many others) were on to an “attitude” problem which McClellan and his crowd had barely concealed during the 2BR campaign. The problem is that Pope, having identified the problem, proceeded on the “wrong” facts. Art. 5 specifies cashiering for the types of statements Porter made to Marble, so we don’t need to resort to the technical crime of treason.

I read this article and the following exchange with great interest. As Jacob Cox’s biographer, I am always interested to see how others view his performance on the battlefields.

Lest we forget, unlike everyone else noted above, he was not a West Point graduate and, at the time of the Battle of Antietam, had been part of the Army of the Potomac for all of two weeks and 9th Corps commander for all of two days. The responsibility he had on September 17, 1862 was enormous — and therefore a sign of the confidence both Burnside and McClellan had in him. At the same time, because of the command confusion (the Burnside/Porter/McClellan imbroglio and Burnside’s reduced “wing” authority), Cox had, as you noted, a minimal staff to carry it out. Burnside said he could use his staff, even as Burnside took his diffident approach to the battle. (As Cox told his wife later, Burnside was commanding one person, Cox, and he, Cox, was commanding the corps). Cox was in a very difficult position between Burn and Mac, and he did what he could, coming within a very short time of routing the rebel right that afternoon.

As for the overall thesis of the article, yes, McClellan had a limited victory since Lee abandoned the field and, eventually, his campaign to the North. At the same time, a few minor adjustments in his strategy, most importantly to attack both flanks at the same time in the morning instead of waiting until late morning to do so on his left, could have been led to a more complete victory.

The latter is what keeps debates like these going, and why the Civil War remains a focus of interest for so many.

Assigning a “Victory” to one of the combatants on the field during the Civil War was tenuous at best. There were a handful of clear cut victories, Chancellorsville, Chickamauga, Franklin and Nashville come to mind. There were also battles, where after the fighting subsided, the victor was in as desperate straights as the vanquished. Shiloh, Antietam, Stones River and Gettysburg could all fall into this category. The victor in these instances was the army that held the field at the end of the day.

Assigning a “Victory” to combatants during the Civil War was tenuous at best. There were a number of clear cut victories. Chancellorsville, Chickamauga, Franklin and Nashville come to mind. In most cases after the fighting had subsided the “victor” was is as desperate straights as the vanquished like at Shiloh, Antietam, Stones River and arguably Gettysburg. In these cases Victory was attached to the army that held the field at the end of the day.

Often times assigning “Victory” to combatants in the Civil War was tenuous at best. There were several clear cut victories. Chancellorsville, Chickamauga, Franklin and Nashville come to mind. Oftentimes after battles the “victor” was in as bad a straights as the vanquished. In those cases “Victory” seemed to be assigned to the army that held the field at the end of the day. Shiloh, Antietam, Stones River and arguably Gettysburg fall into this category.

Kevin: Great job of summarizing a climactic and cataclysmic event! After reading the above discussions, I feel compelled as a fellow guide and longtime student of the MD Campaign to offer the following in SUPPORT of your thesis.

(1) Those who consider the “odds” or ratio of troops between the two sides at Antietam often fail to consider the MAJOR differences in troop experience. Nearly 25% of McClellans AOP had been in the army for 22 days. There was NO “boot camp” or combat infantry training. The troops learned “the drill” on the march and in camps and gained their experience on the field where there were 2 types of soldiers: the quick and the dead. That said, about 1/3 of the ANV was made up of troops that had been with the army (and it’s prides soars) from the beginning of the war; about 1/3 had been in at least one major engagement with Lee, and the remaining 1/3 were somewhere “in between.” Consider that although the ANV had shed about 1/3 of its 71,000 from the beginning of Sept to its crossing of the Potomac due to casualties, sickness, disease, straggling and desertion, they were “high in spirits” and “full of fight.”

(2) By contrast, Mac had been given command just TWO WEEKS before of an eclectic mass of soldiers spread all over/around Washington that were totally demoralized and disorganized. His initial orders from Lincoln? GET LEE OUT OF MD! In less than a week, he pulled these troops together and had them on the road looking for Lee and his army … all the while organizing his command and addressing MAJOR logistical issues. Some of these troops went into battle on the 17th having never loaded (much less fired) their weapons until that day! A sharp contrast between the two armies.

(3) As for the constant hammering on Mac about overestimating the enemy, I’m reminded of one of our fellow guides and historian who often describes this as “Lee the Great” against “George the Timid.” How true. Still, many fail to consider that Mac didn’t “know” what we know, today. We all know how accurately the media covers today’s events (yeah, right) and it was no different in 1862. Many Union observers were touting that Lee brought as many as 200,000 across the Potomac. Was is often overlooked is Mac wasn’t “buying” it. Through his own means of assessment, he concluded that Lee had (more/less) 120,000. By the time he is presented with a copy of Lee’s SO 191, he attempts to pursue him while his army is divided and “gobble” him up in pieces. Hence, the Battle of South Mountain, which by the way, has often been overlooked until recent studies. Pretty gutsy for a general with organizational & logistical issues who thinks he’s outnumbered.

(4). Anyone who knows ANYTHING about the terrain at Antietam, I mean “boots on the ground” knowledge, knows that there are major ridges in the rolling terrain in every direction. Consider the major ridge just south of the Boonsboro pike (west of the Antietam) and you soon understand Macs orders to Burnside, one of his trusted subordinates. He basically gave him discression early in the day. But Burn is too busy pouting over the dissolution of the wing structure and Lord knows, Jacob D Cox was no Jessie Reno. When Burn finally carries the creek on the southern flank, instead of resupplying his troops with ammo and maintaining momentum, he puts the attack in “park” for TWO HOURS while he brings everything but the “kitchen sink” across the Antietam. Sadly enough, this is JUST enough time for Lee to be rescued. Add to this that the AOP’s southern flank was not only totally exposed but manned by “green” troops … in the army barely 22 days and didn’t understand the drill (what they could hear), in total chaos! Can you imagine the outcome of the battle had the IX Corps been “waiting” when AP Hill arrived? Of course, we’ll never know but one would hope that the end result would have been substantially in favor of the AOP (given the overwhelming odds in the AOPs favor before Hill’s arrival). While Mac is ultimately “responsible” and accountable for the outcome, his Corps commander really dropped the ball.

(5). We must consider that the ANV was not alone on its diminished supply of artillery ammo. The AOP was in the same predicament and while Mac had promptly telegraphed for resupplying, the fact is that it wouldn’t arrive for days. Add to this the condition of his army after the battle (as addressed in previous discussions) and it’s not hard to see why he was idle on the 18th.

(6). Finally, let us consider that besides the trophies in Mac’s possession, he DID accomplish Lincoln’s initial orders. He drove Lee from MD; even though he left “on his own”, Lee didn’t have the staying power to survive another fight.

Also often overlooked by McClellan bathers is that Mac was the architect of the powerful AOP (upon which others would build) that lead to the eventual distraction of the ANV. The Union can be glad there was a George B. McClellan in Sept of 1862. Tks again, Kevin.

– Gary

It is important to continue the discussion of the Maryland Campaign. Unlike Gettysburg, there are not new books and articles coming out on a regular basis (i.e. monthly) on Antietam. The editing and publication of the Carmen Papers by Dr. Tom Clemens at long last gives the public access to Carmen’s important and venerable “first draft” of the campaign. One more volume is expected from Tom this year focusing on the biographies of the men who corresponded with Carmen. Balance and objectivity were introduced to the study of the Maryland Campaign by Dr. Harsh’s trilogy in the early 1990s. Primarily focusing on Lee’s strategic and operational leadership, it also includes concise and important summaries of his opponent George B. McClellan as the campaign unfolded. We can only wait for the long awaited Volume 2 of Scott Hartwig’s masterful account of the Maryland Campaign. Telling the story of the day of battle at Antietam, Scott will undoubtedly continue his tradition of objectivity, masterful interpretation, and skillful synthesis of the story, in prose reminiscent of Bruce Catton. Author and historian Steve Stotelmyer has a book of essays on the leadership of George McClellan coming out this year. Titled Too Useful to Sacrifice, Steve will reconsider McClellan’s leadership at Antietam. Historians like Joe Harsh, Tom Clemens, Scott Hartwig and Steve Stotelmyer wipe the slate clean. They scrape the rust and old paint off of generations of old interpretations and expose the bare metal. Kevin Pawlak is among the new generation of young historians who will continue that tradition. I have enjoyed reading Kevin’s article and the series of respectful points and counterpoints made by other readers, and I look for much more from him.

I would make one point in the comparison of Lee’s action at Chancellorsville with respect to replacing Jackson with Stuart and McClellan’s reaction to the loss of corps commanders Hooker and Mansfield. McClellan fully endorsed Hooker’s determination to replace himself (were he to fall) with George Meade instead of Abner Doubleday or James Ricketts. At the next level down, when division commander Israel Richardson fell, McClellan reached outside of the ranks of the Second Corps and selected a capable brigade commander in the Sixth Corps, Winfield Scott Hancock to replace him. No one would argue on the merits of Meade and Hancock.

Excellent points (ALL), James!

– Gary

Jim: I agree on the value of this back and forth – and you make interesting (and valid) points on the changes in command, but they (Meade, who you mention, and Williams, who you don’t mention) ought to serve the purpose of further minimizing the impact of losing corps commanders who were still introducing themselves to their commands. My point about Lee simply was that the loss of Jackson quite frankly was more devastating for a multitude of reasons than was losing Reno/Mansfield/Hooker and not only because of the even more critical circumstances in which it occurred. Yet historians haven’t had to indulge in a detailed analysis of why that prevented Lee from administering a solid defeat on his opponent, I guess that I see the overarching McClellan “problem” as this: Numerous well thought-out and -analyzed arguments are made by folks who urge a “revisionist’ take on McClellan. But on a “macro” level they inevitably end up “explaining” or rationalizing what happened (or didn’t happen) under his leadership. It’s equivalent to evaluating the career of an athlete who, despite being a high draft pick, knocking the scouting rankings off the charts, and piling up some good stats, never….quite……won……hardware. There’s always, in the end, an “explanation” or an “excuse”. That’s not dissimilar to McClellan’s own accounts of his tenure in command.

Whilst Joseph Harsh indeed states 24,000 in 5th and 6th Corps, this is PFD.

Ezra Carman of course tried to work out “effective strength”, with some success and some failures (for some regiments he accepts PFD figures, whilst acknowledging these are an overestimate). He didn’t do this for the 9 brigades and 1 battery he classified as “unengaged” (although be his definitions there should be three “unengaged batteries”). We can estimate the unengaged strength thus:

Sykes’ regulars: Lovell gives his effective strength three days later in his Shepherdstown report, and arithmetic can thus determine the strength of those battalions, assuming the companies in Buchanan’s unengaged battalions are average we get a total of 978 unengaged infantry.

Warren: the 5th NY history gives effective strength, and if one assumes the 10th NY is the same ratio then this little demi-brigade has 225 infantry.

Morell’s division: 5,407 PFD from which we can deduct 3×118 for the batteries = 5,053 infantry (plus 1 battery of 118 counted as “unengaged”). Estimating effectives at 75% would give 3,790 unengaged infantry. Carman said effective strength was 60-80% of PFD. Since ca. 30% of the infantry were raw recruits this may be an overestimate of several hundred effectives.

Franklin’s 5 brigades: Frankin said he had 8,100 effectives at South Mountain, and deducting 533 SM casualties and Irwin (already counted) leaves 5,883 (assume all are infantry).

In summary – one should add ca. 10,876 unengaged infantry on the field of which only Sykes’ 978 regulars and one brigade of Morell (one of the stronger ones, say 1,400- 1,500 effectives) where held in reserve.

Personally I think Carman by accepting PFD (especially of the raw regiments) overestimated effectives thus: 2nd Corps by ca. 2,966 infantry, 9th Corps by 3,357 infantry and 12th Corps by 1,654 infantry (7,977 total).

Thus:

Infantry: 46,146 engaged (Carman), plus 10,876 unengaged = 57,022 – 7,977 overestimates = 49,055 infantry effectives

Artillery: 5,982 plus 118 (one battery in Morell’s division) = 6,100

Cavalry: Carman includes units off the field – adding together companies and multiply by the average of returns estimates 2,636 cavalry on the field.

Effective strength on the field (17th September) = 57,791

I really loved your article I thought it was extremely well thought-out and well laid out for the reader to understand. Well most people have Gettysburg as their baby for lack of a better term I’ve always been partial to Antietam with Vicksburg coming up behind. I have always felt without a doubt that tactically George McClellan and the aop had one the day, but generally I stay away from that when I read most articles or blogs because you’re immediately attacked. But the truth of the matter is sometimes to see who won the battle tactically you have to look at the bigger picture in other words what were the goals of the Commander’s strategically. Reading Ezra’s trilogy gave me a chance to read all of Robert E. Lee letters and correspondence 2 Jefferson Davis which I one of probably come across except in the OR. My point is that in Reading those letters you find the goal of Robert E. Lee is not to March into Maryland and fight but to hopefully get all the way into Pennsylvania at least before he even pics a spot for battle and assuming he wins that to go on to Baltimore Philadelphia or even Washington DC. So for me as a huge fan and someone that reads and studies everything Antietam always when people argue the tactically Antietam was a draw I feel like opening my locker of just Antietam notes and books and showing them Robert E Lee thought he was going to Philadelphia not only did he not make it even to Pennsylvania he got turned around in Maryland with only about two-thirds of the men he came with, so to say it was a draw to me is Ludacris. So again your article was extremely enlightening expressly explaining why Robert E Lee did what he did with his Left Flank in the upper Bridges I never really understood why he did what he did until I read your article so great job as usual and love your site guys and women. And again I do apologize for the grammar, my next media device better have a much more efficient talk-to-text mechanism. Take care God bless everyone