Returning Yell for Yell: The Rebel Yell’s Antebellum Origins

Today, we are pleased to welcome guest author Matthew Guillen.

The Rebel Yell was much romanticized during and after the war. Despite the popular belief in the Yell’s death with the death of the Confederacy, it also enjoyed wide currency after the war, as discussed in Craig A. Warren’s 2014, The Rebel Yell: A Cultural History.[1] Warren’s book represents the first scholarly attention given the Yell in over fifty years, the only other academic study being Allen Walker Read’s 1961 article, “The Rebel Yell as a Linguistic Problem.”[2] Read’s and Warren’s works provide a comprehensive discussion of the Rebel Yell’s sound, uses and effects during the war, and its historiography. Still in need of illumination, however, is the Yell’s antebellum origin. As Warren notes, the Rebel Yell did not emerge spontaneously in 1861, but was a result of existing Southern aural culture and suggests “students of the South’s aural and spoken history should strive to learn more about such screeching as it existed before 1861.”[3]

The assumption that the Rebel Yell was born out of the Civil War is understandable, given the popular (but apocryphal[4]) story of the Yell’s advent in Stonewall Jackson’s admonishing his troops to “yell like furies,” at First Manassas.[5] Despite this tale’s currency, the earliest accounts establish the Rebel Yell’s use prior to July 1861 and anything Jackson may have said.[6] Because Confederate soldiers, from the war’s beginning, yelled in a peculiarly unique way, the reasonable assumption is that the phenomenon had its roots in the prewar period.

This assumption and the search for the Yell’s roots have spawned various theories of varying likelihood.[7] Little wonder that Warren concludes, “the Rebel Yell had no clear parentage,”[8] rather it “emerged from a wide range of calls and yells at work within the antebellum and wartime South.”[9] While certainly true concerning the Yell as a product of many influences, to assert “no clear parentage” devalues what the weight of evidence suggests, namely Native American influence.

Many wartime descriptions of the Rebel Yell connected it with the Native American war whoop. Englishman FitzGerald Ross believed that Southerners “learnt it from the Indians.”[10] London Times correspondent William Howard Russell used the term “whooping” with its Indian connotations to describe the Southern cheer in 1861[11] and in 1863 described it as having “a touch of the Indian war-whoop.”[12] American writer Augustine Duganne dubbed it “a mingling of Indian whoop and wolf-howl.”[13] Postwar, J. Harvey Dew, wrote “in the charge that the ‘war-whoop’ was heard.”[14] It is found too in Frances Baylor’s 1886 novel about the misadventures of an English family in America, On Both Sides. “Where did you get it,” asks Sir Robert at a gathering of Confederate veterans, “Who invented it? Is it an adaptation of some war-cry of the North American Indians? It sounds like what one would fancy their cries might be, doesn’t it?”[15]

Allen Walker Read was inclined toward the “Indian war whoop…[as] the stronger influence.”[16] Craig A. Warren dismisses it because “many southerners delivered shrill screams that had little in common with Native American war cries.” Furthermore, Warren asserts, “most commentators who heard the Rebel Yell firsthand had no problem discerning between it and authentic Indian battle cries,” citing Rufus Dawes’s, Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers.[17] “The Indians of the seventh Wisconsin regiment took an active part in this skirmishing…they would run across the open field at the top of their speed, and…give a shout or war whoop.”[18] Since Dawes also describes Confederate yelling, but does not compare it to Indian shouting, Warren concludes that to Dawes, “the two sounds were different.”[19] While not unreasonable, this conclusion relies on a lack of evidence (and what that may imply) instead of evidence. Indeed, the form this influence took was likely white imitation of Native whooping, rather than appropriation of the “authentic” sound.

The notion of whites before the Civil War imitating Indian war cries is not recent. Mara L. Pratt-Chadwick’s 1896 Revolutionary Pioneers for the Young People describes the final assault at King’s Mountain in 1780 as

One spring! The hill was reached! “Yell, boys, yell!” shouted Sevier; and the Tennessee yell rang out upon the air. Yell on yell, like the whoop of Indians! The forests resounded with it! The echoes rolled it back! The British felt their courage waver, for well had they come to know what kind of men these were who rushed to battle with a yell that rivaled the Indian whoop. “The yelling fiends!” said De Peyster, Ferguson’s second in command.[20]

Miscellanies, by an Officer was originally published in 1813 by Arent DePeyster, mentioned above. The grandson of his nephew, John Watts de Peyster edited an 1888 edition of that work and asserts, “Unquestionably these yells were an imitation of the war-whoop.”[21]

Moreover, a cursory search quickly reveals numerous instances of antebellum whites mimicking Indian shouts. James Adair, an Irishman who lived nearly forty years among Indians in the mid eighteenth century, described how, “as sentinel to prevent our being surprised by the Chocktah, and discovered them crawling on the ground behind trees…I immediately put up the war whoop.”[22]

James Moody was a loyalist during the Revolutionary War, serving with the New Jersey Volunteers. His memoir described how in 1780 he led six men to rescue a comrade held prisoner in New York. Approaching the jail,

Mr. Moody’s men, who were well skilled in the Indian war-whoop, made the air resound with such a variety of hideous yells, as soon left them nothing to fear from the inhabitants of New Town…. “the Indians… are come!”—said the panic-struck people.”[23]

In 1818, John McDonell was examined during court proceedings in Upper Canada. He was considered something of an expert on Indians, having lived near them for over twenty years. The examiner wondered whether “hearing this whoop given is not an alarming circumstance, a sure presage of war and hostilities?” On the contrary, replied McDonell, “I have frequently given it myself.”[24]

John Sprague, in his history of the Second Seminole War (1835-1842), described how when the American infantry charged, they were responded to by the crack of rifles and the shrill, unceasing war-whoop. The soldiers returned it with redoubled energy…. Yell after yell reverberated through the dense foliage…the whoop, which became louder and louder until the shrill voice of the savage was lost in the repeated imitations and shouts of the soldiers…the troops returning yell for yell.[25]

Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal in 1844 described an encounter between whites and Native Americans. “When the general volley…rendered the Indians for a moment incautious, [we] gave them the benefit of our nine rifles, adding, gratis, a sort of imitation war-whoop, got up extempore for the occasion.”[26]

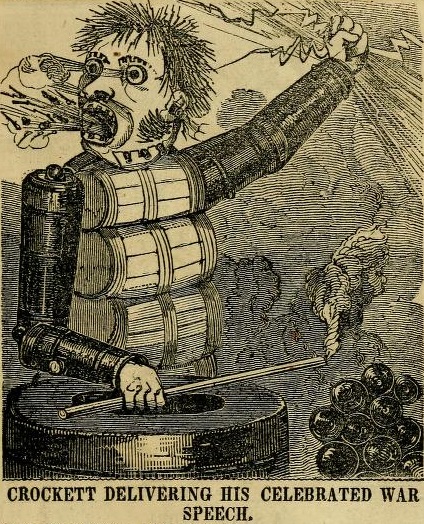

In Davy Crockett’s Alamanac of 1847, a comic engraving depicts “Crockett Delivering His Celebrated War Speech,” in which he instructs his “fellow citizens and humans,” to, “pierce the heart of the enemy…and tarrify him with a rale injun yell,” amongst other unpleasantries. [27]

The practice was so recognizable it into popular literature. In Johnson Jones Hooper’s 1858 novel, Adventures of Captain Simon Suggs, Simon, “in high spirits…raised himself in the stirrups, yelled a tolerably fair imitation of a Creek war-whoop, and shouted–‘I’m off, old stud!’”[28]

The source material suggests the Rebel Yell’s parentage in Native American war cries, the link being white imitation and use on and off the battlefield. Warren is correct “that for several generation leading up to the Civil War, collective yelling without words or cadence functioned as a common vocal practice among southern whites.”[29] However, this practice was evidently not limited to Southerners as Warren assumes, but occurred throughout North America. It is yet worth further inquiry why this practice apparently waned in the North, but endured and flourished in the South, manifesting on the battlefields of the Civil War.

Bibliography

Adair, James. The History of the American Indians. London, 1775.

Baylor, Frances Courtenay. On Both Sides. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1886.

Catlin, George. Life Amongst the Indians: A Book for Youth. London: Sampson Low, Son & Co., 1861.

Chambers, William and Robert Chambers. Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal: Volume I. Edinburgh: William and Robert Chambers, 1844.

“Crockett Delivering His Celebrated War Speech.” Davy Crockett’s Alamanc. Boston: James Fisher, 1847.

Dabney, Robert Lewis. Life and Campaigns of Lieut.-Gen. Thomas J. Jackson, (Stonewall Jackson). New York: Blelock & Co., 1866.

Dawes, Rufus R. Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers. Marietta, OH: E. R. Alderman & Sons, 1890.

De Peyster, J. Watts ed. Miscellanies, by an Officer. New York: A. E. Chasmer, 1888.

Dew, J. Harvey. “The Yankee and Rebel Yells.” The Century Illustrated Magazine (November 1891, to April 1892), 953-55.

Duganne, A. J. H. Twenty Months in the Department of the Gulf. New York, 1865.

Hooper, Johnson Jones. Adventures of Captain Simon Suggs, Late of the Tallapoosa Volunteers; together with “Taking the Census” and Other Alabama Sketches. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 1993.

Moody, James. Lieut. James Moody’s Narrative of His Exertions and Sufferings in the Cause of Government, Since the Year 1776. London: Richardson and Urquhart, 1783.

Pratt-Chadwick, Mara L. Revolutionary Pioneers for the Young People. Bloomington, IL: Public-School Publishing Company, 1896.

Read, Allen Walker. “The Rebel Yell as a Linguistic Problem.” American Speech (May 1961), 83-92.

Report of the Proceedings Connected with the Dispute Between the Earl of Selkirk and the North-West Company. London: B. McMillan, 1819.

Ross, FitzGerald, “A Visit to the Cities and Camps of the Confederate States, 1863-64,” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine (July—December, 1864), 656.

Russell, William Howard, My Diary North and South. Boston: T. O. H. P. Burnham, 1863.

Smith-Rosenberg, Carroll. Disorderly Conduct: Visions of Gender in Victorian America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

—. Pictures of Southern Life, Social, Political, and Military. New York: James G. Gregory, 1861.

Smollett, Tobias George. Continuation of the Complete History of England: Volume the Third. London, 1760.

Sprague, John Titcomb. The Origin, Progress, and the Conclusions of the Florida War. New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1848.

Warren Craig A. The Rebel Yell: A Cultural History. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2014.

[1] Craig A. Warren, The Rebel Yell: A Cultural History (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2014), 162.

[2] Allen Walker Read, “The Rebel Yell as a Linguistic Problem,” American Speech (May 1961), 83-92.

[3] Warren, 159.

[4] Warren, 53-58.

[5] Robert Lewis Dabney, Life and Campaigns of Lieut.-Gen. Thomas J. Jackson, (Stonewall Jackson) (New York: Blelock & Co., 1866), 223.

[6] Read, 83.

[7] Warren, 39-63.

[8] Ibid., 66.

[9] Ibid., 39.

[10] FitzGerald Ross, “A Visit to the Cities and Camps of the Confederate States,” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine (July—December, 1864), 656.

[11] William Howard Russell, Pictures of Southern Life, Social, Political, and Military (New York: James G. Gregory, 1861), 123.

[12] William Howard Russell, My Diary North and South (Boston: T. O. H. P. Burnham, 1863), 312.

[13] A. J. H. Duganne, Twenty Months in the Department of the Gulf (New York, 1865), 148.

[14] J. Harvey Dew, “The Yankee and Rebel Yells,” The Century Illustrated Magazine (November 1891, to April 1892), 953.

[15] Frances Courtenay Baylor, On Both Sides (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1886), 431.

[16] Read, 92.

[17] Warren, 44.

[18] Rufus R. Dawes, Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers (Marietta, OH: E. R. Alderman & Sons, 1890), 265.

[19] Warren, 44.

[20] Mara L. Pratt-Chadwick, Revolutionary Pioneers for the Young People (Bloomington, IL: Public-School Publishing Company, 1896), 80-81.

[21] J. Watts De Peyster, ed., Miscellanies, by an Officer (New York: A. E. Chasmer, 1888), clii.

[22] James Adair, The History of the American Indians (London, 1775), 336.

[23] James Moody, Lieut. James Moody’s Narrative of His Exertions and Sufferings in the Cause of Government, Since the Year 1776 (London: Richardson and Urquhart, 1783), 17.

[24] Report of the Proceedings Connected with the Dispute Between the Earl of Selkirk and the North-West Company (London: B. McMillan, 1819), 153-54.

[25] John Titcomb Sprague, The Origin, Progress, and the Conclusions of the Florida War (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1848), 457.

[26] William Chambers and Robert Chambers, Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal: Volume I (Edinburgh: William and Robert Chambers, 1844), 250.

[27] “Crockett Delivering His Celebrated War Speech,” Davy Crockett’s Alamanc (Boston: James Fisher, 1847).

[28] Johnson Jones Hooper, Adventures of Captain Simon Suggs, Late of the Talllapoosa Volunteers; together with “Taking the Census” and Other Alabama Sketches(Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 1993), 30.

[29] Warren, 159.

Interesting topic !

There is a tape from the Museum of the Confederacy (now renamed) that has authentic yells from Confederate veterans, then “mixed” to simulate larger units giving the yell. Both vets, one on each coast, give virtually the same yell, back in the early days of sound recording.

This information is available in “Not Billy Idols’s ‘Rebel Yell,'” on ECW. The link is above in Related.

I just looked/listened to the hyper-links associated with the above-mentioned article. They are at the “Not Billy Idol’s” article. I hate the Confederacy with all my heart, but when I heard the yell learned at the Cedar Creek re-enactment as taught by Mr. Kidd, and based on the work of the Museum of the Confederacy (which may now have a more politically-correct name), I have to admit that there were tears on my face. Very, very moving.

“Attack and Die” by Grady McWhiney & Perry Jamieson, (a book much criticized by some Southerners) connects the Rebel Yell with the Celtic heritage of many Southerners. On page 190 “Note that yelling–indeed, a special kind of yelling–was an intrinsic part of the Celtic charge.”

On page 191, “Available evidence suggests that the Rebel yell was a variation on traditional Celtic animal calls, especially those used to call cattle, hogs, and hunting dogs. ‘Who-whoey! who-ey! who-ey!’ is the way one man remembered it with ‘the first syllable ‘woh’ short and low, and the second ‘who’ with a very high and prolonged note deflecting upon the third syllable ‘ey.'”

Totally was going to refer to the southerner’s Scot-Irish heritage which would be Scot for all intents and purposes. Not one of the bibliographies quote my mom from Mississippi who hailed from rebels and understood that the origin was Scot as they screamed and wailed in battle also. (See the film Braveheart) I believe the rebel yell as a Scot invention may be more authentic than Queen Isabella of France consorting with William Wallace in her tent.