Like Sheep

The use of cliché is prevalent in Civil War combat narratives. Every attacking force, by their description, always had to charge through “a hail of grape and canister.” This was repeated ad nauseam regardless of whether or not there was even artillery present at the assaulted point. Historians often borrow such descriptions, and who can blame them. Civil War soldiers would scoff at the notion that we have any subject matter authority. “No man can form any idea of what it is like to go into a battle or charge without having been in one,” wrote Private William L. Phillips, 5th Wisconsin Infanty, on April 1, 1865, one day before his mortal wounding at the Petersburg Breakthrough.[1]

The use of cliché is prevalent in Civil War combat narratives. Every attacking force, by their description, always had to charge through “a hail of grape and canister.” This was repeated ad nauseam regardless of whether or not there was even artillery present at the assaulted point. Historians often borrow such descriptions, and who can blame them. Civil War soldiers would scoff at the notion that we have any subject matter authority. “No man can form any idea of what it is like to go into a battle or charge without having been in one,” wrote Private William L. Phillips, 5th Wisconsin Infanty, on April 1, 1865, one day before his mortal wounding at the Petersburg Breakthrough.[1]

Honest soldiers, themselves, admit not knowing the full scope of the engagement. “I am not one of those who can give a detailed account of an entire battlefront of many miles as is sometimes attempted by some writers,” admitted Sergeant John R. King, 6th Maryland Infantry. “My observations never covered greater territory than my regimental front; more often, a company front. Whenever the spirit moves me to write of any engagement or campaign, I confine my narrative to the part taken by my own regiment.”[2] King further went on to mostly quote from the official records in describing the Breakthrough for the National Tribune newspaper.

“The story of Petersburg will never be written,” claimed Adjutant William Hugh McLaurin of the 18th North Carolina Infantry. “Even those who went through the trying ordeal can not recall a satisfactory outline of the weird and graphic occurrences of that stormy period.”[3]

And so we collectively turn to cliché.

A crutch I’ve seen before in the past is the analogy to sheep. This appears twice in the archival materials I have since compiled for the Breakthrough, both from New York regiments in Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour’s division. What stands out is the remarkably different meaning behind their use.

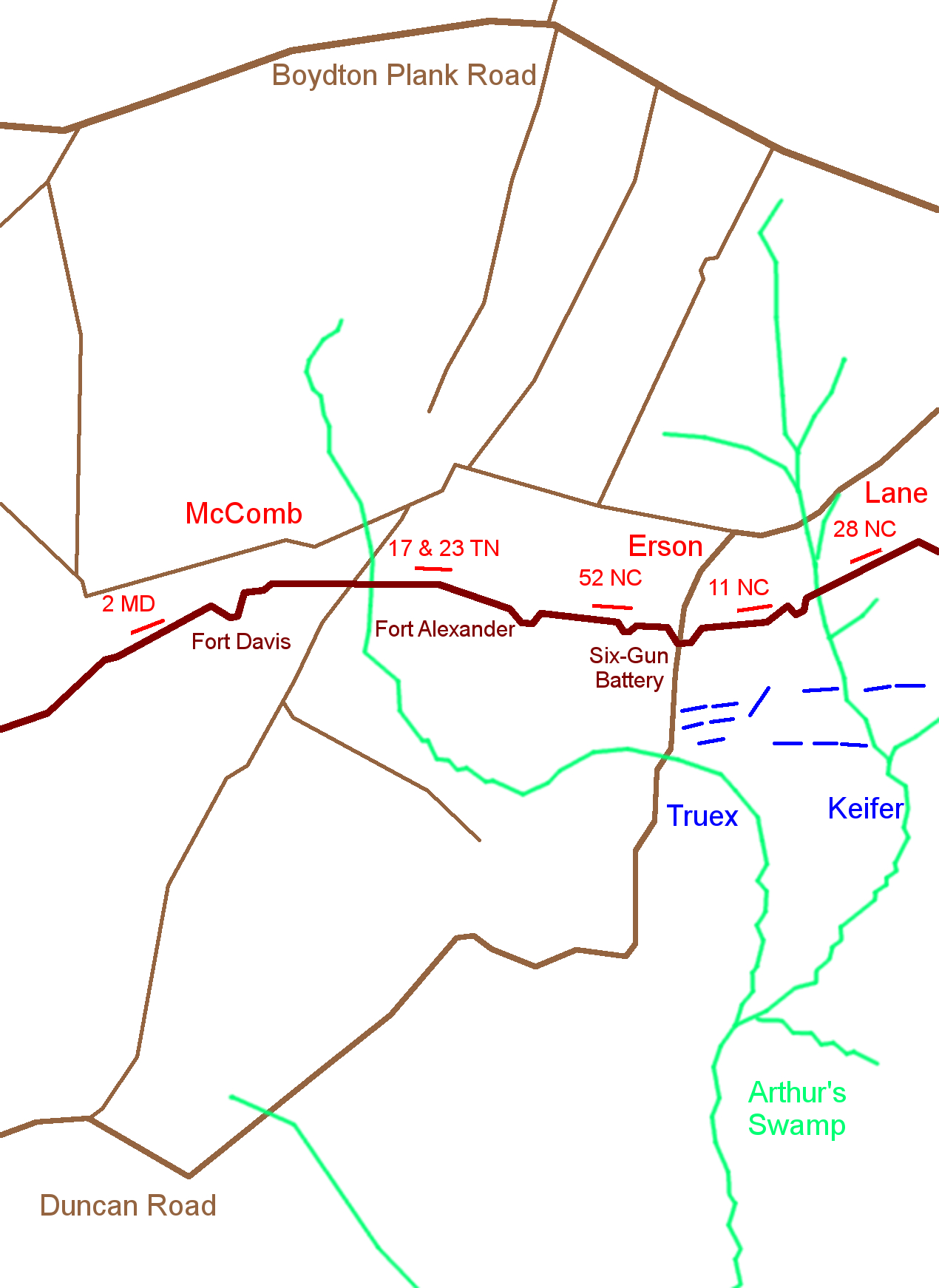

Seymour’s two brigades crashed over the Confederate earthworks manned by the 11th, 28th, and 52nd North Carolina regiments along the middle branch of Arthur’s Swamp on April 2, 1865. After breaking through the Tarheel line just at dawn, Seymour’s command swept along the inner side of the Confederate works and carried a series of batteries as they fought through Brig. Gen. William McComb’s brigade to Fort Davis.

“We broke the enemy’s lines and flanked him and captured their line of forts and turned their own artillery on them and drove them like sheep before a flock of wolves,” claimed Private Simon Burdick Cummins, 151st New York Artillery.[4]

“The Johns was panic stricken and run like sheep,” he claimed in another letter. “They (the prisoners) said they well knew what was coming when we began to howl.” Cummins often turned to cliché in his writing. He’s guilty in the same message to his parents of utilizing perhaps the most common phrase: “mowed the Johnnies down like grass.”[5]

We read this quotes and as historians eagerly regurgitate them. I particularly use Simon’s as often as I can. Forgive me for slipping into cliché, though. I have to for sentimental reasons. Simon’s a distant relative, my second cousin four times removed.

But where he used sheep to describe the Confederates, another New Yorker, an anonymous officer in the 9th New York Artillery, had a different perspective.

These Yankees served as infantry during the Breakthrough and composed the second line of Col. J. Warren Keifer’s brigade. This officer, quoted in the regimental history, wrote about having to whack his soldiers with the flat side of his sword to coax them forward in the assault. At each layer of abatis, the men once more took cover and needed further encouragement. The frustrated officer provided the least inspiring description I’ve ever read about that triumphant moment when the bluecoats breached the Confederate lines.

“Like a lot of sheep, over a stone wall, we go into the enemy’s works.”[6]

That’s one way of putting it. Read Cummins and this account without the dates and you would hardly think it’s the same battle. We need these competing quotes, though, otherwise you’ll get a too romanticized version of combat. The worst offender I’ve found is from Capt. Merritt Barber, who commanded the Vermont Brigade after Brig. Gen. Lewis Addison Grant was wounded by picket fire preliminary to the assault. This glossy rendition of the Breakthrough somehow made it into the official records:

After passing over about half the distance the enemy began to pour in a well-directed musketry fire from the front and artillery fire from forts on either hand, which completely enfiladed the line and caused it to waver. This was the most critical moment throughout the entire engagement. Day was just beginning to dawn and very soon the enemy would be able to discover our precise position and movements. They had also become apprised of the point of attack and were apparently beginning to appreciate its importance, and were hastening to meet it with all the strength at their disposal.

But, to the credit of the command, the hesitation was but momentary, and the troops again pushed forward with a determination that knew no such word as fail. The remaining portion of the ground was passed over under a most withering fire of musketry, but with a gallantry that was never surpassed, and which betokened the victory subsequently won. Officers and men vied with each other in the race for the works, and all organization was lost in the eagerness and enthusiasm of the troops. The line of abatis was brushed away like cobwebs and the men swarmed over the works with yells and cheers that struck terror to the rebels flying in all directions.[7]

Once again I’ll admit to using this quote in the past, and I will continue to in the future. You can’t turn down sound bites like that. Just make sure you include a healthy dose of realism. And be sure to never rely too much on one particular source.

Sources:

[1] Phillips, William L. to “Father and Mother,” April 1, 1865. William L. Phillips Letters. MSS 142S, State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

[2] King, Jno. R. “Sixth Corps at Petersburg. Its Splendid Assault, Which Broke the Main Line of the Rebels.” National Tribune, April 15, 1920.

[3] McLaurin, William H. “Eighteenth Regiment.” Walter Clark, ed. Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-’65, Volume 2. Goldsboro, NC: Nash Brothers, 1901, 59-60.

[4] Cummins, Simon B. to “Dear Mother & Sisters,” April 14, 1865. Melvin Jones, ed. Give God the Glory: Memoirs of a Civil War Soldier. Calumet, MI: Greenlee Printing Company, 1997, 161.

[5] Cummins, Simon B. to “Dear Father and Mother,” April 3, 1865. Melvin Jones, ed. Give God the Glory: Memoirs of a Civil War Soldier. Calumet, MI: Greenlee Printing Company, 1997, 156.

[6] Roe, Alfred S. The Ninth New York Heavy Artillery: A History of its Organization, Services in the Defenses of Washington, Marches, Camps, Battles, and Muster-out, with Accounts of Life in a Rebel Prison, Personal Experiences, Names and Addresses of Surviving Members, Personal Sketches, and a Complete Roster of the Regiment. Worcester, MA: Published by the Author, 1899, 228.

[7] Barber, Merritt. Report, April 15, 1865. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Volume 46, Part 1. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894, 968-969.

EXCELLENT ADVICE WHETHER ONE IS WRITING OR RESEARCHING OR FORMING A OPINION. THANK YOU

Good advice for writers, and I enjoyed the quotes.