Gettysburg Off the Beaten Path: The Wounding Site of Daniel Sickles

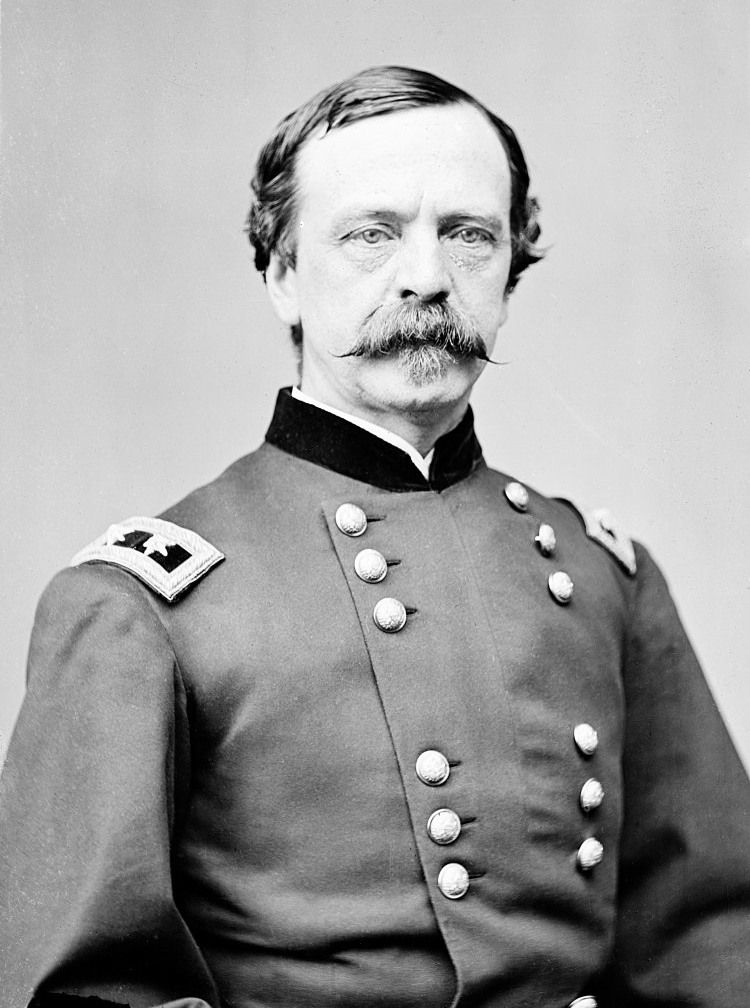

Major General Daniel Sickles was the wild card in the Army of the Potomac, and a survivor.

Sickles was a prewar lawyer and politician who was tried, and acquitted for, the murder of Philip Barton Key in 1859. Known for shady political dealing, as well as the possible employment of a bordello mistress, he may be the only corps commander to have the occupation of “pimp” on his resume, according to biographer James A. Hessler. He also could put survivor on his resume too.

“He had a very bumptious air, and talked in a high falsetto voice with a pursing of his lips,” recalled artist James Kelly in a post war interview, “an arching of the eyebrows, and a tilting of the chin; with an over-articulation of his words, in an effort vulgarians give when they are trying to make the impression that they are very genteel. Later, when I met [actor] Lester Wallack, I saw that Sickles was a crude copy of his appearance and manner.”

Although acquitted of murder, utilizing the first successful use of temporary insanity in a United States court, most would not associate with him and “blemished character.” After Sickles took back his wife, who was having an affair with Key, Sickles resumed his duties in the U.S. House of Representatives. Southern diarist Mary Chesnut noted from the house gallery that Sickles was, “left alone as if he had the smallpox.”

At the outbreak of war Sickles asked Gov. Edwin Morgan of New York if he could raise a regiment to command. The political backing of the powerful Tammany Hall political machine still made Sickles a formidable man. Morgan authorized Sickles not to regiment, but an entire brigade of five regiments instead.

Sickles performed well at his first true test in battle, at Williamsburg, in 1862—though he spent the better part of 1862 away from his unit recruiting for the Union cause.

By December 1862 he was at the head of a division, and after hitching his wagon to another up and comer with no scruples, Joe Hooker, Sickles found himself at the head of the 3rd Corps. Hooker felt that Sickles “is one of the greatest soldiers of the day.” Charles Francis Adams had a different view of Sickles, Hooker, and his chief-of-staff Daniel Butterfield; “Sickles, Butterfield, and Hooker are the disgrace and bane of this army; they are our three humbugs, intriguers, and demagogues.” Provost Marshal Marsena Patrick thought, “Sickles & most of his crew, are poor—very poor…”

By July 1863, Sickles was entering just his second battle as a corps commander. At Chancellorsville, two months prior, his corps fought well but sustained heavy casualties which included the loss of two division commanders. Both Sickles and former army commander Joe Hooker misinterpreted Lee’s battle plan. Assuming that Lee was retreating, Sickles corps was pressed forward as a reconnaissance-in-force, then left more than a mile from the main Federal lines as Hooker prepared to pursue the presumed fleeing rebel army. By the time that Hooker unraveled Lee’s plan it was far too late. Sickles corps attempted to reestablish its place in line with the rest of the army, but found itself cutoff. By luck, the 3rd Corps did happen upon one of the strongest positions in the Chancellorsville area, Hazel Grove. The position of Hazel Grove threatened Lee’s army, while providing a strong artillery platform. Hooker though ordered Sickles men away from the position, and shortly thereafter Lee’s artillery positioned itself, and dominated the Federal line.

Throughout July 2nd, Sickles corps positioned and re-positioned itself time and again like a listless sleeper. The corps came onto the battlefield in piecemeal fashion late on July 1st, and into the morning of July 2nd. Meade wanted the corps to extend his line south along Cemetery Ridge, in the direction of Little Round Top. Sickles had reservations about this line.

While the assigned position had a few small knolls and hillocks that were somewhat defensible, his corps lacked the manpower to stretch all the way to Little Round Top. The front of the position was dominated by an approximately 1 mile plateau like ridge line that ran along the Emmitsburg Road. The road itself ran on a northeast axis towards the town.

Sickles faced a similar situation at Chancellorsville, there though, he was force to give up said high ground. At Gettysburg, it loomed in front of him like an inviting mistress.

Riding to headquarters around mid-morning, “Devil Dan,” as he was nicknamed, parlayed with Meade. The former begged to have the authority to advance his line forward to the desired ground. Meade refused. Working on but a few hours sleep, a high stress level, and planning an offensive of his own preoccupied the commanding general elsewhere. Thus, Meade was not in the bargaining mood. He did consent to send the chief of artillery of the army, Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt to Sickles front, with the instructions to place his corps “within the limits of the general instructions I have given you; any ground within those limits you choose to occupy, I leave to you.” The two officers set off to scout Sickles proposed position.

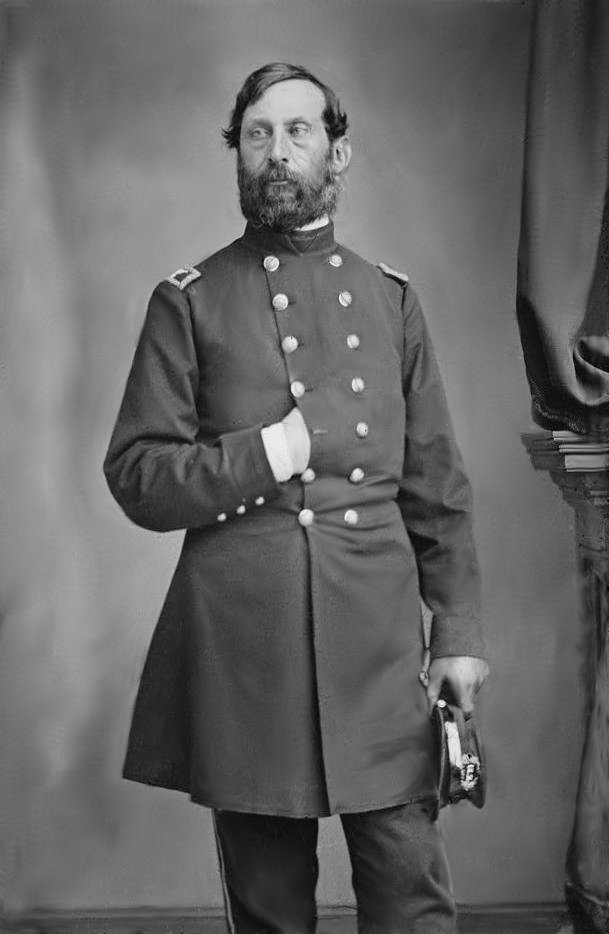

Henry Jackson Hunt was the perfect officer to accompany Sickles on his inspection tour of the south end of the field. Hunt, an 1839 graduate of West Point, was also the leading authority in artillery in the entire army. The man literally wrote the manual that the Federal artillerymen used. Although he was a truly “by the book” officer, Hunt had an eagle’s eye for terrain and artillery positions on a battlefield.

Sickles showed the staff officer the ground upon which he was supposed to deploy his corps. In the postwar years Sickles told Hunt that Meade’s proposed line was, “a low, marshy swale and a rocky, wooded belt unfit for artillery & [a] bad front for infantry. Hence my anxiety to get out of the hole where I was & move up to the commanding ground.”

Sickles proposed line was double edged sword. While the Emmitsburg Road line “commanded all the ground behind, as well as in front…and together constituted a favorable position for the enemy to hold.” Hunt thought that Sickles line was “tactically the better of the two…” If held by the Federals, would be difficult to maintain.

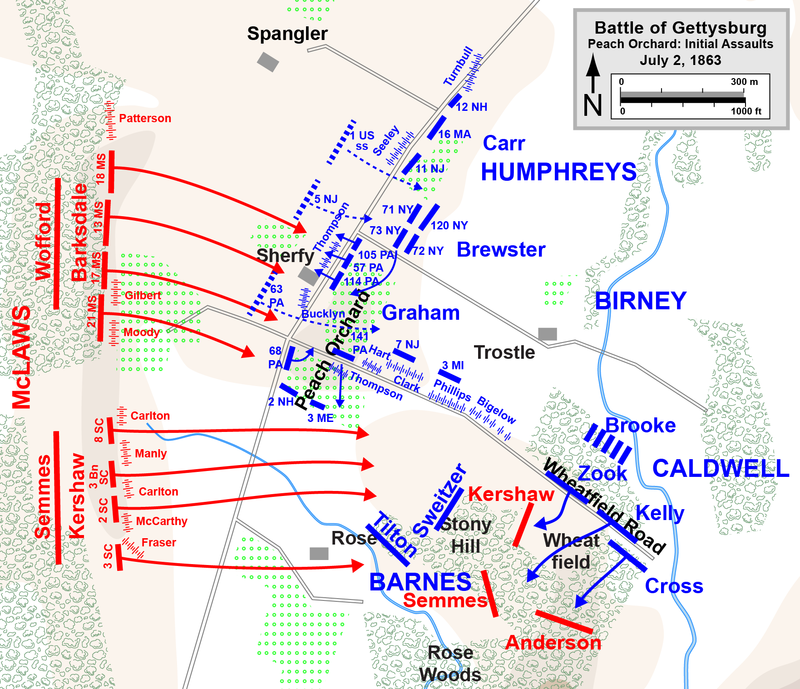

The new proposed line would run diagonally from near the base of Little Round Top in a northwesterly direction to its apex at the Peach Orchard, this would constitute the left flank of the 3rd Corps. The right flank would then run in a northeasterly direction toward Gettysburg, aligning its self parallel with the Emmitsburg Road. This line would create a salient angle, or a portion of the line that protruded outward, akin to a pimple in the line. A salient was vulnerable to fire from multiple points, specifically enemy artillery fire that could converge on the Federal position; whereas the Federal counter-battery fire would be diverging fire, which is diluted by having to pick many targets rather than one massive one.

The apex at the Peach Orchard was 1,500 yards from the closest infantry support. At its closest point to the Cemetery Ridge line was on the right flank, and was still nearly a half mile from reinforcements on Cemetery Ridge.

Finally, the proposed line was more than one and a half times longer than the line the 3rd Corps was ordered to hold. Which meant that Sickles would need more men to hold said line. Sickles entered the Chancellorsville Campaign with 18,721 officer and men, making it the second largest corps in the army. But the attrition of battle there cost some 4,119 casualties and subsequent expiration of enlistments on the way to Gettysburg weakened the corps to 10,674 men, making it the third weakest corps in Meade’s army.

Sickles finally asked Hunt directly if he would authorize a move of the 3rd Corps forward. “Not on my authority,” Hunt responded curtly. “I will report to General Meade for his instructions.” In Sickles warped sense of reality Hunt meant that the position “met with the approval of his [Hunt’s]…judgment….” As Hunt rode toward Meade’s headquarters at the Lydia Leister house, Sickles prepared his men for their forward movement and destiny.

“Soon the long lines of the Third Corps are seen advancing, and how splendidly they marched.” Opined Maj. St. Clair Mulholland. “It looks like a dress parade, [or] a review.” Hancock, “resting on one knee [and ] leaning upon his sword…smiled and remarked: ‘Wait a moment, you will soon see them tumbling back.’”

Like a petulant child that screamed for ice cream all day, Sickles assumed his forward position, even though the parent wasn’t aware the child had taken the ice cream.

Brigadier General Alexander Webb thought that “He [Sickles] could fight, yes; as a tactician, no.” Sickles and his men were in the fight of their lives.

Later in life Winfield Scott Hancock would joke, “There is the peach orchard where Sickles went down and got licked, repeating with a laugh, where Sickles went down and got licked.”

Two divisions of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s Confederate First Corps struck Sickles line with the fury of a hurricane. The Federal line collapsed in Devil’s Den. There was an intense whirlpool like battle ragging in the Wheatfield. In the Peach Orchard and along the Emmitsburg Road Sickles line was swept away from left to right. Rebel guns were rushed forward and planted on the Peach Orchard plateau, just as Sickles had feared.

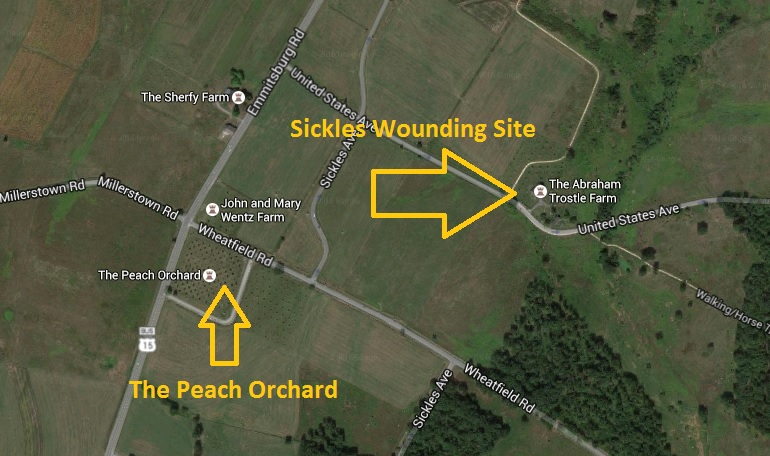

From his headquarters at the Trostle Farm, he and his staff witnessed the downfall of his corps. The 3rd Corps commander was “surrounded by a large staff, [and] was in a state of excitement; the enemy’s shot were dropping about him, and he seemed to be very much confused and uncertain in his movements.” It was evident that the area was, “too hot for a corps headquarters; not so much from fire directed at that point…[but] on account of high shots coming over the crest on both sides and centering there.” One of those death dealing shells found their mark with Sickles right leg.

The general claimed that “I never knew I was hit…Suddenly I was conscious of dampness along the lower part of my high-top boots and pulling it out I was surprised to see it dripping with blood……I lifted it carefully over my horse’s neck and slid to the ground…the knee had been smashed, probably by a piece of shell, and that the leg had been broken above and also below the knee….”

Staff officers scooped up the general and carried him over to the nearby Trostle Barn. “General, are you hurt?” inquired a dumbfounded staff officer. “Tell General [David] Birney he must take command,” Sickles replied. Bandaging Sickles with their handkerchiefs and attempting to staunch the bleeding with a saddle strap, it was clear that the general was in no shape to keep to the field.

Fearing capture by the Confederates above all else at this moment, the general was placed on a litter and evacuated from the field. It is alleged that he propped himself on his elbows and puffed on a cigar as he was taken to the 3rd Corps field hospital. This was the second corps commander Meade had lost in as many days.

The leg of Sickles was amputated at the 3rd Corps hospital by Dr. Thomas Sim, the Corps Medical Director. That amputation may have taken place at the Daniel Shaeffer Farm along the Baltimore Pike. Sickles detractor Alexander Webb claimed that Sickles “wound was only a slight one, but he saw the blunder he had made in placing his men where he did, that he ordered a surgeon to cut off his leg, but he refused. In fact, if I remember right, two surgeons refused to do it; and at last, he ordered a drunken volunteer surgeon to do it, and he did it.” The truth was that the wound was serious enough to necessitate an amputation, though the cloak of Devil Dan’s reputation even obscured the most straightforward facts in the general’s life.

Sickles never returned to command the 3rd Corps, or any corps for that matter, in the Army of the Potomac. In October of 1863 he returned to army headquarters looking for reinstatement. In the latter stages of the Gettysburg Campaign Meade assigned Maj. Gen. William “Blinky” French to command 3rd Corps. French outranked Sickles (by date of promotion), and Meade had little use for a non-West Point, loose cannon, Hooker-man to be part of his senior chain-of-command. Meade also refused field service to Sickles on the basis that he was sans one leg. Sickles countered by saying that Confederate Second Corps commander Richard Ewell only had one leg and was allowed to serve under Lee. (It should also be noted that Oliver Otis Howard served as the 11th Corps commander at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg with only one arm.) It was a moot point. Meade had made up his mind. Devil Dan was out of the Army of the Potomac. Sickles anger would rear its ugly head later that winter, but that is a story for another time.

The leg itself was a celebrity. Keeping it as a macabre souvenir. Eventually he donated the limb to the Army Medical Museum in Washington D.C. The general supposedly visited the limb on the anniversary of its amputation.

A monument sits on the northwest side of the Trostle Barn. The monument was placed in 1901 and denotes the approximate location of Sickles wounding.

One officer later grumbled, “If Sickles had not lost his leg, he would have lost his head.”

Authors Note:

Sickles headquarters was on the Abraham Trostle Farm, which was 134 acres at the time of the battle. Abraham and his wife Catherine had been leasing the farm from Abraham’s father Peter, for the previous 15 years. In 1863, according to noted Gettysburg historian Gregory Coco, the farm was “being tilled by George W. Trostle,” because Abraham was in a lunatic asylum for an alleged fist fight. The damages to the home, out buildings, and land were substantial. In the large Pennsylvania bank barn, a cannonball created a large hole in the upper part of the structure. There were 16 dead horses close to the house, and a total of 100 dead horses on the property. The battle inflicted $3,153.50 worth of damage to the property. The damages totaled nearly half of their net worth, and the Trostle’s were never compensated for their troubles. In 1899 the farm was sold to the Gettysburg National Military Park Commission for the sum of $4,500.

To Reach the Trostle Farm:

-From the town square, follow Baltimore Street South for 0.5 miles.

-At the Y Intersection, bear to the right and follow Steinwehr Ave., which will turn into -Business 15 South (Emmitsburg Road).

-Follow Business 15 South (Emmitsburg Road) for 1.7 miles.

-Turn left onto United States Ave.

-Follow United States Ave. and park in the designated parking area near the barn. The monument is on the west side of the barn (left side as you face it).

PLEASE NOTE THAT THIS IS A PRIVATE RESIDENCY. PLEASE RESPECT THE TENANTS’ PRIVACY AND DO NOT KNOCK ON THE DOOR AND ASK TO TOUR THE HOME. DO NOT ENTER THE BARN, WHICH IS NOT OPEN TO THE PUBLIC.

When I lived in Silver Spring in the ’90s, I went to see Sickles’s leg at Walter Reed. It has since been moved to the Army Medical Museum. The number of men who went from politics into command, and then back into politics is pretty amazing. I commend these men for putting, literally, their blood and their gold into the fight. Not all were great commanders, but then, not all West Point grads were, either. It is easy to refer to these men as ready to exploit any situation for their own aggrandizement, but I do not think anyone can fault Sickles’s intentions. His judgement perhaps, but not his intentions.

One of these days I hope to visit my Great Grand Uncles leg. . I have a copy of a letter that Gen. Longstreet wrote in 1902 to Dan Sickles ..Part of the letter reads” it is now conceded that your Corp’s move to the Peach orchard saved the battle for the Union Cause’ It is the saddest reflection of my life.”

Signed Confederate General

Longstreet.

Sickles was my grandfather’s close friend and a guest in our home.