“Come on You Wolverines”: Remembering the Fight at East Cavalry Field

Today, East Cavalry Field is a relatively quiet place on an otherwise busy battlefield. I have been there many times and often spending a few hours on each visit. It is indeed rare to encounter anyone there, compared to the crowds at Devil’s Den, the High Water Mark or Little Round Top. On July 3, 1863, those farm fields southeast of Gettysburg were not a tranquil place. An engagement between Union and Confederate cavalry unfolded in the farm fields southeast of Gettysburg. Interestingly enough, the objectives for the commanders involved, Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart and Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg, were completely different.

With the brigades of Brig. Gens. Fitzhugh Lee, Wade Hampton, John Chambliss and Col. Vincent Witcher, Stuart set out toward the Confederate left. He was prepared to guard the army’s flank but also to attack the enemy if an opportunity presented itself. With that idea in mind, Stuart planned to use high ground known as Cress’ Ridge to set an ambush for the Federals. Stuart attempted to use a similar tactic the following May at the Battle of Yellow Tavern.

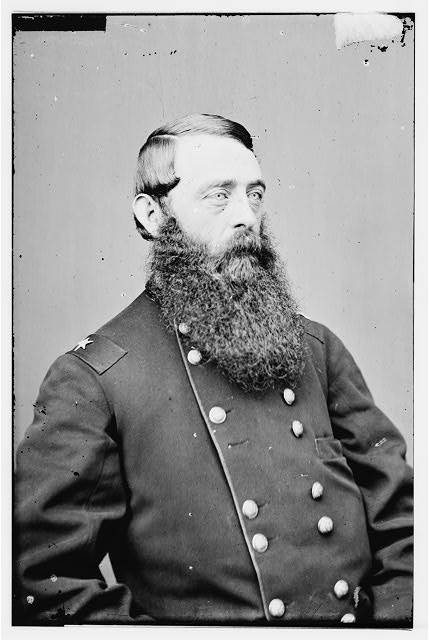

Gregg’s assignment that day was to secure and hold the intersection of the Hanover and Low Dutch Roads. Whoever controlled it had ready access to the Baltimore Pike, a vital thoroughfare should the Army of the Potomac be forced to retreat. To accomplish this effort, Gregg had one of his brigades under Col. John McIntosh along with a detached brigade from the Third Cavalry Division led by Brig. Gen. George Armstrong Custer.

The field over which Stuart and Gregg fought is essentially bounded in the east by the Low Dutch Road, on the south by the Hanover Road and to the north and west by Cress’ Ridge. Union and Confederate opened the battle early in the afternoon.. Battery M, 2nd U.S. Artillery commanded by Lt. Alexander Pennington engaged Captain Thomas Jackson’s Charlottesville Horse Artillery. Pennington was eventually joined by guns from Batteries E and G, 1st U.S. Artillery under Captain Alanson Randol. As the day wore on, the Union guns eventually gained the upper hand over their counterparts. This dominance contributed to the eventual Union victory.

The cavalry fighting commenced when Witcher’s 34th Virginia advanced dismounted against elements from McIntosh’s brigade. This force consisted of two battalions of the 1st New Jersey, two squadrons of the 3rd Pennsylvania and the Purnell Legion (Maryland) posted near the Rummel Farm at the base of Cress’ Ridge. Reinforced by elements of the 14th Virginia and 16th Virginia, the 34th Virginia eventually launched a charge that drove the Federals from their position. To stem the gray tide, Custer sent his own 5th Michigan forward. As the 5th Michigan engaged the Virginians, the 1st Virginia from Lee’s brigade and the 9th Virginia and 13th Virginia from Chambliss’ brigade advanced mounted to join the fight. With ammunition running low and threatened with being overwhelmed, Gregg ordered Custer to charge. Riding at the head of the 7th Michigan, Custer shouted “Come On You Wolverines” and led them in the assault. The Seventh’s attack covered the withdrawal of their sister regiment and for the time being, stopped the advance of the 9th Virginia and 13th Virginia. The 1st Virginia, however, held firm and were joined by the 1st North Carolina and Jeff Davis Legion from Hampton’s brigade. This additional weight forced Custer to order the 7th Michigan to retreat.

The withdrawal of the 7th Michigan marked a transition in the see-saw battle. After pushing forward regiments piece-meal throughout the afternoon, Lee and Hampton now advanced together in a mounted charge from Cress’ Ridge toward the intersection of the Hanover and Low Dutch Roads. Custer had kept the 1st Michigan, his veteran regiment, in reserve for such a circumstance. Once again, Gregg ordered him to charge. The Wolverines went in again, Custer leading them and riding four lengths in advance of the regiment. They slammed into the Confederate troopers and a hand to hand melee ensued. Joined by elements from the 5th Michigan, along with the 1st New Jersey and 3rd Pennsylvania, the Federal cavalry managed to break up the enemy advance and forced the Confederates to retreat and effectively ended the fighting.

While aspects of the battle are extremely well documented, it seems that East Cavalry Field has transcended into myth. Theories abound (although I do not subscribe to them) that Stuart’s mission on July 3 was to launch a major assault on the Union lines in conjunction with the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble assault on Cemetery Ridge. Stuart, however, makes no mention of such a plan in his official report of the campaign. The myth has also minimized the participation of Union officers while inflating the actions of others. It is often misunderstood that George Custer directed the fight at East Cavalry Field and thus he continues to receive much of the credit in the popular mind for the victory. While Custer and his brigade played a vital role, so too did John McIntosh and his troopers. Moreover, David M. Gregg had command of the field. He skillfully directed the deployments of his troopers and turned in an excellent performance. It was just one of many in an impressive and often overlooked career. At the same time, we should not be too surprised at how views of the fight have morphed over time. Myth has tended to surround battles in which George Armstrong Custer was a participant. East Cavalry Field is no different than the others.

On the 150th anniversary of the battle, we set up this battle as a miniature wargame. I was expecting the players to engage in exciting charges and counter-charges. However, the Union commander dismounted the cavalry and used the fire power of the repeating and breech-loading carbines, plus cannister, to shred the Confederate charges. While the attackers did have some success in over-running some of the Union skirmish lines, in the end, their losses were too heavy to continue. I guess that Custer’s aggressive style of combat did not consider such totally a defensive approach! I hope the kind readers do not object to this injection of gaming into this scholarly site.

ALWAYS inject gaming! Or anything else–cats, recipes, wives . . . we welcome all!

Since I was a young kid, I’ve heard repeatedly the claim that Custer saved the Army of the Potomac and the Battle of Gettysburg by besting Stuart on the third day. So many quality comanders lost to history because of the myth makers around some. If there was no Little Bighorn and no Lizzie Custer controlling the story afterwards, Custer himself would be just a small footnote in history.

Right now reading Edward Longacre’s history of the Michigan Cavalry Brigade, CUSTER AND HIS WOLVERINES.

Custer indeed played a part but it was by no means his battle. Hollywood has also perpetuated the East Cavalry Field myth. While Custer is most remembered for the last 36-48 hours of his life, I’m not sure he would be small footnote. From the summer of 1863 through to Appomattox he is one of the top, but not the best, brigade/division commanders in the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry corps. Despite his court martial and suspension in 1867, he returns with a strong performance in the Southern Campaigns of 1868-69. His reputation was solidified by the Yellowstone and Black Hills Expeditions in 1873 and 1874. I find that fascinating because from 1870 until his death I think he is looking for either a way out of active field campaigning or out of the army entirely. I think you will enjoy Custer and His Wolverines, it is a very interesting read.

” Custer leading them and riding four lengths in advance of the regiment. “- says it all about this engagement and Autie. Thanks for posting this.

I would like to know more about the role of the 34th Virginia and its sister regiments in this battle.

Bryce A. Suderow

streetstories@juno.com

Thanks, Bryce. I appreciate the kind words. I believe, and forgive me as I am on the road at the moment, but there is some great material on the 34th Virginia and their sister regiments in the first two volumes of the Bachelder papers.

I wish Daniel Davis would write more about this battle, especially the part played by the 34th Virginia cavalry and its two sister regiments.

bryce

Be careful when exploring the East Cavalry Battlefield. When visiting last summer, I was exploring the area along Gregg Avenue just south of the Rummel House when some lady who I presume lives in the house starting yelling at me from across the field. I couldn’t understand her from 500 yards away. Then she got in her car and drove up to me as I was walking along Gregg Avenue and started to yell/harass me about trespassing on her property. I told her there were no “Posted” signs and the NPS map makes no mention of private property. In fact the map shows all the land as “green” or part of the park. She proceeded to argue with me for the next 10 minutes and talked about how Jesus will punish me. It got weird fast. I told her to take it up with the NPS if they didn’t want people walking the fields or the owners should post signs. I later learned that SOME of the land immediately near the old house is still private/in easement, but again, it is not marked as such on the NPS maps, nor is it posted. She lives in the middle of the most famous battlefield in the world — they may get the occasional visitor walking the fields.

In short, watch out for the crazy Rummel lady!! She will bite your head off.