“An Especial Prize to the Boys:” Union Soldiers and the Illustrated News (Part 1)

This is the first of two posts regarding the relationship between Union soldiers and the emerging illustrated press during the Civil War.

The Union soldier of the Civil War had an insatiable hunger for newspapers. Joseph C. G. Kennedy, head of the Census Bureau, concluded in 1860 that “the people of the United States are peculiarly ‘a newspaper-reading nation.”[i] Moreover, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. wrote of newspapers in the U.S. as necessity in 1861: “We must have something to eat, and the papers.… Everything else we can do without.”[ii] James M. McPherson’s essay, ‘“Spend Much Time in Reading the Daily Papers:” The Press and Army Morale in the Civil War,’ illustrates the importance of the weekly and daily newspapers that were shuttled en masse in locomotives and steamboats to the warring armies.

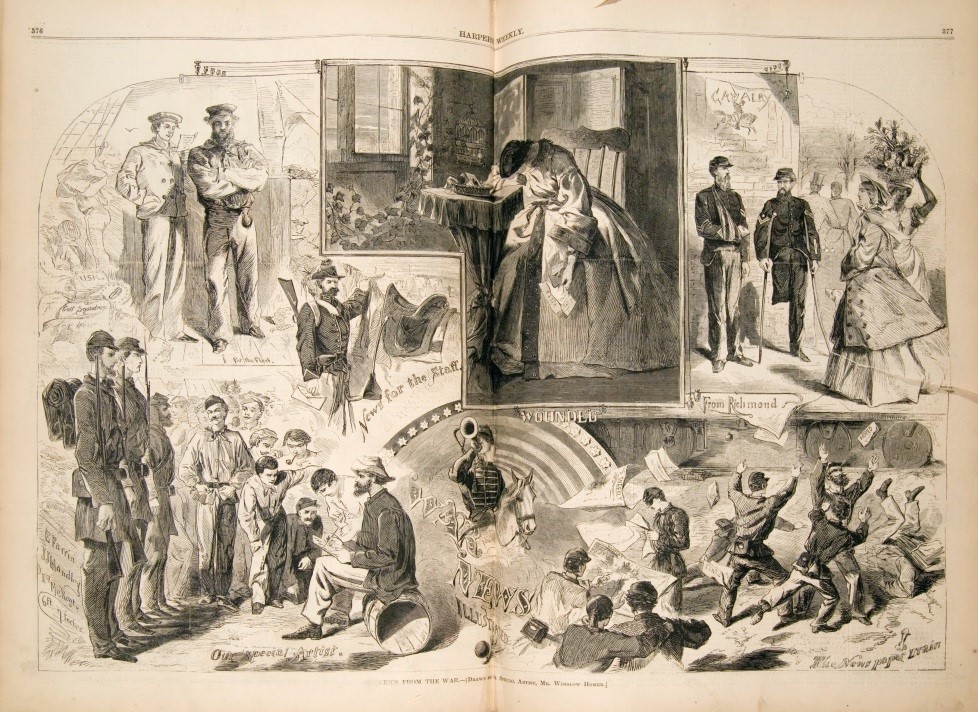

But the illustrated weeklies that came into prominence in the latter half of the 1850s are given brief mention. These journals were especially prized by Federal soldiers for their blending of the textual and the visual; providing a new and innovative dynamic with which to consume information in the war-torn Republic.

Federal soldiers, by their own accounts, were fascinated with the illustrated newspapers. It is logical, for they were becoming a powerful tool in mass-journalism. Though pioneered in Great Britain with the advent of London Illustrated News in 1842, the United States caught up the following decade. Three major pictorial papers rose to prominence in the years preceding the conflict: Leslie’s Illustrated News in 1855; Harper’s Weekly in 1857; and the New York Illustrated News in 1859.[iii] Harper’s and Leslie’s could boast a combined circulation of nearly 200,000 copies per week in 1860. Given that readership far outstrips circulation; there was a significant audience for the pictorial weeklies on the eve of the Civil War. Others newspapers were pressured to follow the trend, with metropolitan dailies such as the New York Herald and the Philadelphia Enquirer including simple woodcut portraits, illustrations, and maps during the war years.

In fact, the availability of pictorial ephemera contributed to a cultural shift in U.S. society. Visual imagery grew in importance for recording and comprehending the conflict. Alvin Coe Voris, a Federal officer stationed on Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, wrote home to his wife in December 1863 that “Illustrated papers are all the rage now. To be up with the times, I thought it best to illuminate my letters to [the children] by some first class sketches.”[iv] Soldiers felt pressured by the commercial success of pictorial newspapers and attempted to emulate the papers’ popular story-telling techniques in their own writings. Soldiers recognised that the illustrated weeklies had a profound impact on the nation-entire. Daniel Wait Howe of the 7th Indiana reminisced that Harper’s Weekly was “among the great papers that helped to mold public opinion in the North… [It’s] utterances exactly sounded the keynote of northern sentiment.” Howe noted that “the striking illustrations of Thomas Nast exercised a powerful influence in shaping northern sentiment.”[v] President Lincoln agreed, apparently titling Nast “our best recruiting sergeant.”[vi]

The illustrated weeklies had as much of an effect on the soldiers in camp as they did on civilians at home. The sketch artist Edwin Forbes wrote of the importance of the illustrated newspaper, noting that “a private soldier’s world, in an active campaign, does not extend far beyond the lines of his brigade.” As the remedy for this lack of information, soldiers “eagerly… longed for the arrival of the newspapers which would bring him news of ‘The Last Great Battle’ – of which he had been a part, yet about which he knew but little.”[vii] The illustrated newspaper widened the narrow horizons of the soldier’s perception in war, regardless of any level of illiteracy among the ranks. Musing on the inherent politicisation of the army as a result of the availability of the illustrated news, Howe wrote in his diary: “Men who scarcely ever read, much less buy, a paper at home, are eager to see one in camp.” The mass-consumption of newspapers by the troops led him to state that “people at home have no idea how well posted and how interested the soldier is in the political questions of the day.”[viii]

The illustrated weeklies were so popular with the soldiers that their engagement with them appeared almost ritualistic to observers. One British eyewitness joining the Army of the Potomac wrote of precious cargo aboard the boat he travelled in:

“We brought with us the Saturday’s illustrated journals… distributed by local and state associations among the soldiers in camp… a curious sight it was to me… a general rustle of opening leaves, and in a moment every man as if it had been part of his drill, was down upon the ground with the same big picture before him.”[i]

Others observed that the papers would undergo frantic examination by the soldiers. Forbes wrote in his memoirs: “The weekly story-papers seemed an especial prize to the “boys,” and passed through many hands.” When finally read, “the pictures were cut out and stuck up, more or less ornamentally, on the walls of the log-shelters [of winter quarters.]”[ii] Maximilian Hartman of the 93rd Pennsylvania Infantry kept a careful record of the newspapers he received during the war in his diary. Between the 19th of February and the 1st of March, 1862, Hartman received three copies of Leslie’s. Hartman’s papers were sent by friends at home, and once he had devoured the information contained within, he sent them back home to his wife to read.[iii]

[i] Robert Ferguson, America During and After the War (London, UK: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer, 1866), p. 74

[ii] Forbes, Thirty Years After, p. 133

[iii] Maximilian Hartman, entries for Feb. 19, 1862; Feb. 22, 1862; Mar. 1, 1862, ‘Typescript Civil War diaries by M. Hartman, Co. B, 93rd Reg. PA,’ 1861-62, 2007.79, Special Collections Research Center, Swem Library, College of William & Mary

[i] Joseph C. G. Kennedy, Preliminary Report on the Eighth Census. 1860 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1862), pp. 102-3

[ii] Louis M. Starr, Reporting the Civil War: The Bohemian Brigade in Action, 1861-1865 (New York, NY: Collier Books, 1962), p. 44, in James M. McPherson, ‘“Spend Much Time in Reading the Daily Papers”: The Press and Army Morale in the Civil War,’ This Mighty Scourge: Perspectives on the Civil War (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 155

[iii] William F. Thompson, The Image of War: The Pictorial Reporting of the American Civil War (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1994), pp. 20-22

[iv] Alvin Coe Voris, to Lydia Voris, ‘Hilton Head, S.C., Dec. 23d, 1863,’ Voris, Alvin Coe, Papers, 1863, Mss1V9154a, Virginia Historical Society Manuscript Collection

[v] Daniel Wait Howe, Civil War Times, 1861-1865 (Indianapolis, IN: The Bowen-Merrill Company Publishers, 1902), pp. 4-5

[vi] Albert Bigelow Paine, Th. Nast, His Period and His Pictures (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1904), p. 69

[vii] Edwin Forbes, Thirty Years After: An Artist’s Story of the Great War (New York, NY: Fords, Howard & Hulbert, 1890), p. 133

[viii] Howe, ‘March 9, 1864,’ diary entry, Civil War Times, pp. 4-5

1 Response to “An Especial Prize to the Boys:” Union Soldiers and the Illustrated News (Part 1)