Chris Kolakowski: Leadership Makes the Difference on New Year’s Eve 1862

We’re two months away from the Fourth Annual Emerging Civil War Symposium at Stevenson Ridge (Aug. 4-6). We’ve asked each of our speakers to share with us a story related to the topic they’ll be presenting as part of our “Great Defenses of the Civil War” line-up. Today, we feature Chris Kolakowski, who’ll be speaking about the Army of the Cumberland at Stones River.

We’re two months away from the Fourth Annual Emerging Civil War Symposium at Stevenson Ridge (Aug. 4-6). We’ve asked each of our speakers to share with us a story related to the topic they’ll be presenting as part of our “Great Defenses of the Civil War” line-up. Today, we feature Chris Kolakowski, who’ll be speaking about the Army of the Cumberland at Stones River.

In any organization, military or civilian, leadership often can make the difference between success or failure. Because returns on decisions are quickly and precisely measured (body counts, battle line movement, etc), the military offers myriad case studies and lessons about leadership concepts. I’ve blogged about moral courage here and the loneliness of command here.

A sterling example of senior command influence occurred on New Year’s Eve 1862, during the first day of the battle of Stones River outside Murfreesboro, Tennessee. The battle, fought between Major General W.S. Rosecrans’ Union Army of the Cumberland (46,000 men) and Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee (36,000 men) from 31 December 1862 to 2 January 1863, occurred during a high-stakes season in which the Union reeled from military and political defeats. In part, Stones River turned on the decisions of Rosecrans and Bragg on the first day.

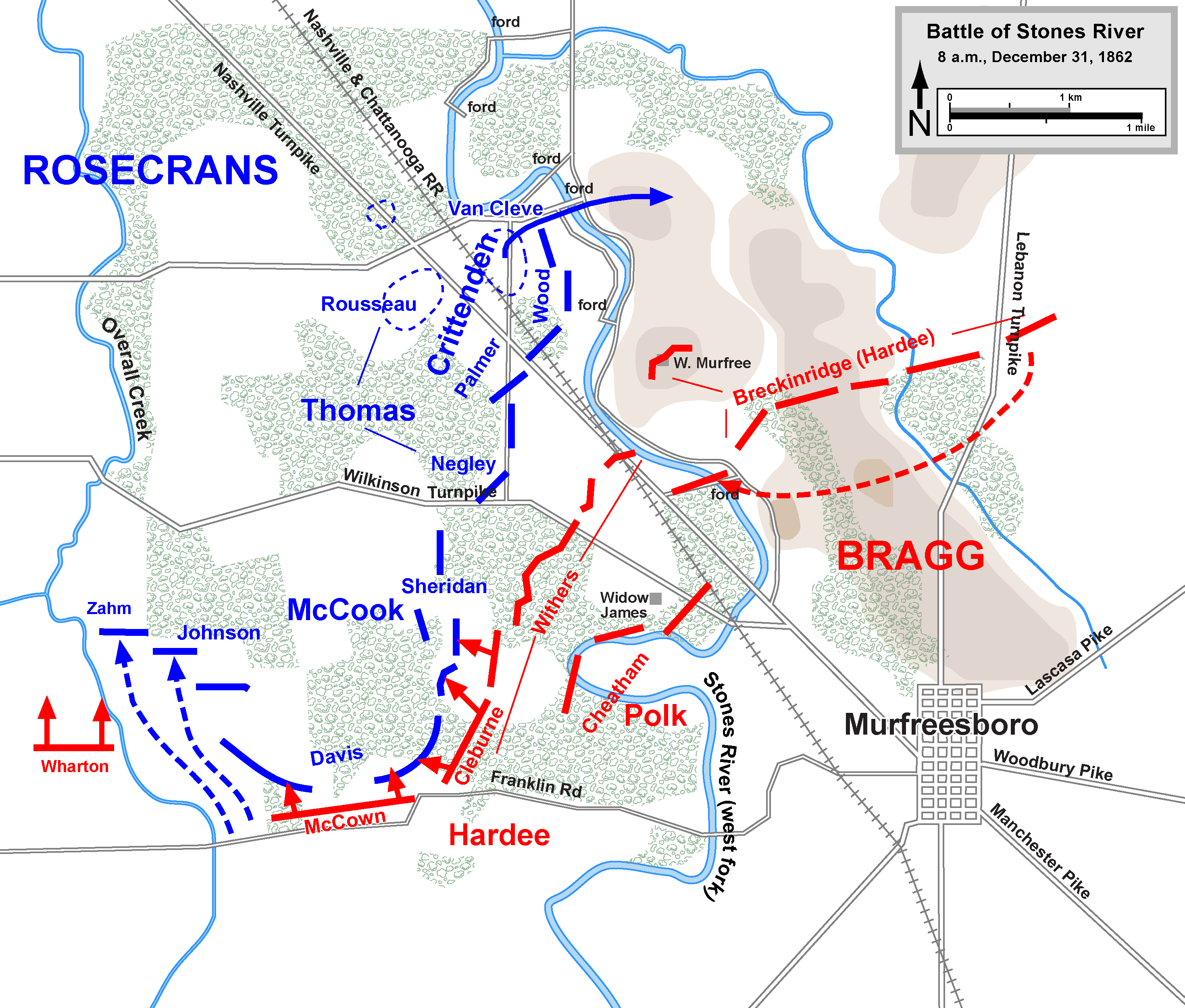

Bragg launched an attack with his left at 6 A.M, with the goal of rolling up the Union army and cutting it off from the Nashville Pike. Rosecrans also planned a strike with his center and left to start at 8 A.M. Rosecrans heard firing at 6:30 on his right, but thought little of it. At 7:30, as his troops deployed, he received a report that the right wing was “heavily pressed,” but did not let it distract him. Just before 8, stragglers appeared, the sounds of battle had moved toward the Union rear, and a more detailed report explained that the right wing had virtually collapsed under a Confederate offensive. The Federal center wing and left wing troops were about to attack, but they also could be called back and used to shore up the right wing. General Rosecrans now faced a choice, upon which rested the fate of his army.

Rosecrans blanched, but quickly recovered his composure. He called off the attack, setting his troops in motion to reinforce the right wing. Only one brigade would be left to watch a key crossing of Stones River, while one division protected the left astride the Nashville Pike – one-third the forces that had been slated for the attack. Rosecrans then personally rode for the front.

Confederate reconnaissance missed this weakness—the commander of the 6,000 men on that side of the river, John C. Breckinridge, feared an attack all morning. Shortly after 10 Bragg (who remained in the rear mostly as a passive observer) directed Breckinridge to attack, but quickly countermanded the order. At midday Breckinridge’s brigades received orders to cross the river and join Army of Tennessee’s main body. The opportunity was lost.

Meanwhile the Federals, bolstered by reinforcements from the left wing, put together a line along the Nashville Pike. Rosecrans was everywhere, insisting the army would win and often personally leading troops into battle. One officer later wrote: “I could not help expressing my gratitude to Providence for having given us a man who was equal to the occasion—a general in fact as well as in name.” The day closed with Breckinridge’s attacks all failing in the final afternoon of 1862.

The handling of Breckinridge’s men on the morning of New Year’s Eve is one of the great what-ifs in Confederate military history. If the Confederate cavalry had scouted better, they would have detected the Federal withdrawal and the infantry could have moved earlier to Hardee or Polk. A tantalizing and bold option would have been to press the attack against the lone brigade on the Federal left; a push across the river there would have put Rosecrans between two powerful attacks from left and right, with no reserves to counteract Breckinridge. This double-barreled pressure would probably have collapsed the entire Federal army. Even without crossing the river, a Confederate attack would have forced Rosecrans to divert men to his left during the critical morning hours, weakening the Nashville Pike defenses to a point possibly beyond retrieval. But boldness was not in Bragg that day, and his mismanagement of Breckinridge’s division cost him the battle.

For his part, Rosecrans won the day with his personal leadership and the leadership of his officers and men. The Army of the Cumberland endured a near-death experience unlike any large Federal army had sustained in the war, but had survived.

Bragg probed the Federal position over the next two days with attacks of varying strengths; he everywhere found resolute Federals determined to hold on. On January 3 Bragg retreated.

Enjoyable read; thank you.

Makes me better appreciate Rosecrans, who seemed to often undermine himself and our ability to appreciate him!

This is a nice entry on Rosecrans. My only concern is that Rosy is becoming the “Next George Thomas” and the table isn’t coming back to level but might be tilting in the other direction.

Thanks, John! I’ll be the first to admit that Rosecrans has his limitations as a commander. None of them, however, were on display on December 31, 1862.