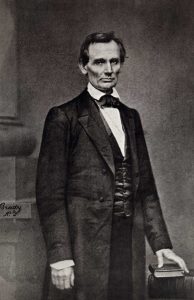

February 27, 1860: Lincoln at Cooper Union

On this day 158 years ago-February 27, 1860-Abraham Lincoln of Illinois delivered an invited speech at the Cooper Institute in New York City. Lincoln had gained a reputation and a following among some Republicans in 1858 when he skillfully debated Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois (a Democrat) as the two ran against one another to represent Illinois in the United States Senate. Though Lincoln lost that election to the incumbent Douglas, he gained important exposure as a skilled speaker and an articulate voice against the expansion of slavery into the western territories. Lincoln wisely arranged to have the texts of the his debates with Douglas published, and by the time he arrived in New York City 158 years ago some thought he might be a potential Republican presidential candidate for 1860. The speech he delivered at the Cooper Institute, now commonly referred to as the Cooper Union speech, solidified Lincoln as a candidate in the minds of many. Less than three months later, the Republican National Convention nominated Abraham Lincoln as its presidential candidate.

The Cooper Union speech was over 7,000 words long, making it one of Lincoln’s longest speeches. Here are some of the key excerpts from the speech in which Lincoln persuasively argues against slavery’s expansion into the West. Notice, however, that he does not call for abolishing slavery where it exists or for an invasion of the South to free slaves-two of the most common complaints from southerners about Lincoln during the 1860 campaign.

“In his speech last autumn, at Columbus, Ohio, as reported in The New-York Times, Senator Douglas said: “Our fathers, when they framed the Government under which we live, understood this question just as well, and even better, than we do now.” I fully indorse this, and I adopt it as a text for this discourse. I so adopt it because it furnishes a precise and an agreed starting point for a discussion between Republicans and that wing of the Democracy headed by Senator Douglas. It simply leaves the inquiry: “What was the understanding those fathers had of the question mentioned?” … The sum of the whole is, that of our thirty-nine fathers who framed the original Constitution, twenty-one—a clear majority of the whole—certainly understood that no proper division of local from federal authority, nor any part of the Constitution, forbade the Federal Government to control slavery in the federal territories; while all the rest probably had the same understanding. Such, unquestionably, was the understanding of our fathers who framed the original Constitution …”

“It is surely safe to assume that the thirty-nine framers of the original Constitution, and the seventy-six members of the Congress which framed the amendments thereto, taken together, do certainly include those who may be fairly called “our fathers who framed the Government under which we live”. And so assuming, I defy any man to show that any one of them ever, in his whole life, declared that, in his understanding, any proper division of local from federal authority, or any part of the Constitution, forbade the Federal Government to control as to slavery in the federal territories. I go a step further. I defy any one to show that any living man in the whole world ever did, prior to the beginning of the present century, (and I might almost say prior to the beginning of the last half of the present century,) declare that, in his understanding, any proper division of local from federal authority, or any part of the Constitution, forbade the Federal Government to control as to slavery in the federal territories. To those who now so declare, I give, not only “our fathers who framed the Government under which we live”, but with them all other living men within the century in which it was framed, among whom to search, and they shall not be able to find the evidence of a single man agreeing with them. …”

“I do not mean to say we are bound to follow implicitly in whatever our fathers did. To do so, would be to discard all the lights of current experience—to reject all progress—all improvement. What I do say is, that if we would supplant the opinions and policy of our fathers in any case, we should do so upon evidence so conclusive, and argument so clear, that even their great authority, fairly considered and weighed, cannot stand; and most surely not in a case whereof we ourselves declare they understood the question better than we. …”

“If any man at this day sincerely believes that a proper division of local from federal authority, or any part of the Constitution, forbids the Federal Government to control as to slavery in the federal territories, he is right to say so, and to enforce his position by all truthful evidence and fair argument which he can. But he has no right to mislead others, who have less access to history, and less leisure to study it, into the false belief that “our fathers who framed the Government under which we live” were of the same opinion—thus substituting falsehood and deception for truthful evidence and fair argument. If any man at this day sincerely believes “our fathers who framed the Government under which we live”, used and applied principles, in other cases, which ought to have led them to understand that a proper division of local from federal authority or some part of the Constitution, forbids the Federal Government to control as to slavery in the federal territories, he is right to say so. But he should, at the same time, brave the responsibility of declaring that, in his opinion, he understands their principles better than they did themselves; and especially should he not shirk that responsibility by asserting that they “understood the question just as well, and even better, than we do now.”

“Let all who believe that “our fathers, who framed the Government under which we live, understood this question just as well, and even better, than we do now”, speak as they spoke, and act as they acted upon it. This is all Republicans ask—all Republicans desire—in relation to slavery. As those fathers marked it, so let it be again marked, as an evil not to be extended, but to be tolerated and protected only because of and so far as its actual presence among us makes that toleration and protection a necessity. Let all the guarantees those fathers gave it, be, not grudgingly, but fully and fairly, maintained. For this Republicans contend, and with this, so far as I know or believe, they will be content. …”

“But you say you are conservative—eminently conservative—while we are revolutionary, destructive, or something of the sort. What is conservatism? Is it not adherence to the old and tried, against the new and untried? We stick to, contend for, the identical old policy on the point in controversy which was adopted by “our fathers who framed the Government under which we live”; while you with one accord reject, and scout, and spit upon that old policy, and insist upon substituting something new. True, you disagree among yourselves as to what that substitute shall be. You are divided on new propositions and plans, but you are unanimous in rejecting and denouncing the old policy of the fathers. Some of you are for reviving the foreign slave trade; some for a Congressional Slave-Code for the Territories; some for Congress forbidding the Territories to prohibit Slavery within their limits; some for maintaining Slavery in the Territories through the judiciary; some for the “gur-reat pur-rinciple” that “if one man would enslave another, no third man should object”, fantastically called “Popular Sovereignty”; but never a man among you is in favor of federal prohibition of slavery in federal territories, according to the practice of “our fathers who framed the Government under which we live”. Not one of all your various plans can show a precedent or an advocate in the century within which our Government originated. Consider, then, whether your claim of conservatism for yourselves, and your charge of destructiveness against us, are based on the most clear and stable foundations. …”

“Human action can be modified to some extent, but human nature cannot be changed. There is a judgment and a feeling against slavery in this nation, which cast at least a million and a half of votes. You cannot destroy that judgment and feeling—that sentiment—by breaking up the political organization which rallies around it. You can scarcely scatter and disperse an army which has been formed into order in the face of your heaviest fire; but if you could, how much would you gain by forcing the sentiment which created it out of the peaceful channel of the ballot-box, into some other channel? …”

“When you make these declarations, you have a specific and well-understood allusion to an assumed Constitutional right of yours, to take slaves into the federal territories, and to hold them there as property. But no such right is specifically written in the Constitution. That instrument is literally silent about any such right. We, on the contrary, deny that such a right has any existence in the Constitution, even by implication. …”

“Your purpose, then, plainly stated, is that you will destroy the Government, unless you be allowed to construe and enforce the Constitution as you please, on all points in dispute between you and us. You will rule or ruin in all events. …”

“An inspection of the Constitution will show that the right of property in a slave is not “distinctly and expressly affirmed” in it. …”

“But you will not abide the election of a Republican president! In that supposed event, you say, you will destroy the Union; and then, you say, the great crime of having destroyed it will be upon us! A highwayman holds a pistol to my ear, and mutters through his teeth, “Stand and deliver, or I shall kill you, and then you will be a murderer!” To be sure, what the robber demanded of me—my money—was my own; and I had a clear right to keep it; but it was no more my own than my vote is my own; and the threat of death to me, to extort my money, and the threat of destruction to the Union, to extort my vote, can scarcely be distinguished in principle. …”

“Wrong as we think slavery is, we can yet afford to let it alone where it is, because that much is due to the necessity arising from its actual presence in the nation; but can we, while our votes will prevent it, allow it to spread into the National Territories, and to overrun us here in these Free States? If our sense of duty forbids this, then let us stand by our duty, fearlessly and effectively. Let us be diverted by none of those sophistical contrivances wherewith we are so industriously plied and belabored—contrivances such as groping for some middle ground between the right and the wrong, vain as the search for a man who should be neither a living man nor a dead man — such as a policy of “don’t care” on a question about which all true men do care — such as Union appeals beseeching true Union men to yield to Disunionists, reversing the divine rule, and calling, not the sinners, but the righteous to repentance — such as invocations to Washington, imploring men to unsay what Washington said, and undo what Washington did. …”

“Neither let us be slandered from our duty by false accusations against us, nor frightened from it by menaces of destruction to the Government nor of dungeons to ourselves. Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.”

Cooper’s Union is still a fabulous space, even though it was somewhat rearranged by the Institution.

I had the unique privilege, on September 6, 2017, when Harold Holzer was honored for his distinguished scholarly work on Lincoln by the New York State Archives Trust, and had a charming conversation with his friend Stephen Lang, to have been close enough to touch the famous decorative table that is part of all the images of Lincoln in the Cooper’s Union.

I’m not usually thrilled by furniture, but that was a special piece. It is in beautiful condition and just radiates history..I restrained myself: I didn’t touch it, just took its picture.

Thanks for including Lincoln’s words. We need more of that nowadays.