Polk’s Resting Place

Leonidas Polk remains something of an elusive figure to military historians. He owed his high rank to his friendship with Jefferson Davis. But Polk could have risen up the officer ranks on his own. He was charismatic, well-connected, wealthy, and a darling of New Orleans society, where he preached secession in the antebellum years as Louisiana’s Episcopal Archbishop. Politically reliable and a fire-eater and Southern nationalist for years before the war, he proved during the conflict to be stubborn and selfish, mostly noted for his long feud with Braxton Bragg, who commanded the Army of Tennessee. Yet he was brave and beloved by his men. He was easy to talk to and eschewed harsh discipline. He also showed some improvement as a commander. In the Atlanta Campaign he transferred a corps to Georgia and ably commanded it at Resaca.

On June 14, 1864, Polk was killed at Pine Mountain during an artillery barrage [ECW’s Chris Mackowski went On Location there in 2017]. As with many generals, he was not given a burial in a place of his choosing or a place dear to him. Central Tennessee and New Orleans, the two areas where he owned land and was a respected figure, were occupied by Union forces. Augusta, Georgia became his resting place. He received an elaborate funeral in Saint Paul’s Church, presided over by Bishop Stephen Elliott of Georgia. He was buried in a location under the present-day altar.

After the Civil War, Polk fit into the Lost Cause mythology. He was dead and, given the religious iconography of the Lost Cause, fit perfectly into its symbols. Yet, he was not part of the Virginia dynasty. He was also not a particularly successful battle commander. Commemoration of Polk mostly revolved around his faith and positive personal anecdotes. For example, he makes periodic appearances in Sam Watkin’s Company Aytch, where is is depicted as a warm and approachable commander.

In 1945 Polk’s body was brought to New Orleans and re-interred at Christ Church Cathedral on St. Charles Avenue. The congregation had an interesting history. During the war, it was pro-secession, and Benjamin Butler closed it for refusing to offer prayers for Abraham Lincoln’s health and success, a common convention in the Episcopal Church. The current cathedral was constructed in 1886-1889. Polk’s old church Trinity Episcopal Church, on Jackson Avenue, still stands and honors the general. Yet, Christ Church is the archbishop’s seat for Louisiana’s Episcopal Church, and therefore the headquarters of Polk’s successors.

On a quiet Saturday after I finished a Garden District tour, I went over to check out Polk’s resting place. I was let in by Reverend Travers C. Koerner. He showed me Polk’s grave, which is to the right of the pulpit. A mourning altar for Jefferson Davis, dating back to his death in New Orleans in 1889, is nearby.

Polk’s bishop’s seat, crafted by the slaves on his plantation, also stood nearby and is roped off to prevent people from sitting in it. In another room a piece of altar art featured Polk looming above one of the many churches he built. Close at hand, another piece of art featured St. George slaying the dragon. Crafted in 1939, the dragon is laced with swastikas. It is another reminder of the falsity of presenting the Confederacy and Nazi Germany as equivalences. The person who crafted this art certainly did not think so in 1939.

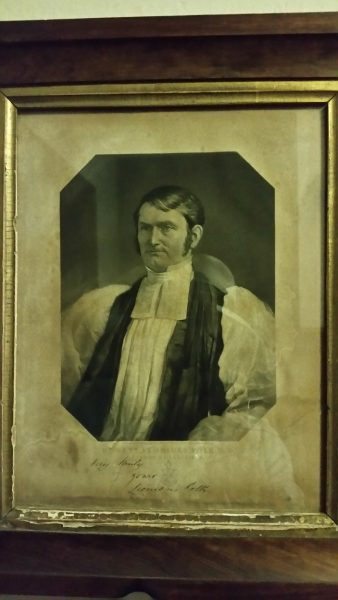

As I left, I spied a simple picture of Polk in his robes. It was not the the old magisterial photograph that adorns many books but rather a simple piece, showing a younger Polk. It reminded me of the several postwar photographs of P.G.T. Beauregard. Unlike his wartime photos, where he is erect and formal, Beauregard was more relaxed in his postwar pictures taken. The images undermine our concrete views of historical figures, who themselves changed as surely as the times they experienced.

Interesting article; thanks for posting.

Sean

My take on Leonidas Polk is that he was a friend of Jefferson Davis who believed he was called back to military duty in “his County’s hour of need.” His development of Fort Columbus was most impressive (and the defenses which included over 120 big guns mounted high above the Mississippi River on a bluff; a barrier chain denying Northern shipping the use of the river south of Cairo Illinois; that barrier chain protected by contact-activated torpedoes; torpedoes converted to land-mines in defense of fort to the back, away from the river; and a garrison of possibly 14,000 men, with additional defense in depth provided by gunboats of the Confederate Navy — all combined to make Fort Columbus practically impregnable.) And an argument could be made that General Beauregard ordered the “Gibraltar of the West” evacuated prematurely…

Major General Polk saw himself as “place-holder,” holding the western end of the Confederate Kentucky Line of Defence while awaiting the arrival of Albert Sidney Johnston (recommended to President Davis by Polk.) When General A. S. Johnston was placed in overall command of Department No.2, MGen Polk agreed to stay in harness until another senior commander was sent west to replace him (unfortunately, that General — PGT Beauregard — was unwell, suffering complications of throat surgery.) And when disaster struck Fort Donelson shortly afterwards, Leonidas Polk was persuaded to stay on (and evacuate his beloved Fort Columbus) for the Good of the Country… joining his Corps of troops to Bragg’s at Corinth Mississippi, with intention to take a mighty Army (commanded by Albert Sidney Johnston) north, defeat U. S. Grant, and drive Don Carlos Buell back to the Ohio River. Unfortunately, Shiloh was not a Southern victory; and General Johnston was killed (and Major General Polk, realizing that His Country needed all the trained leaders it could acquire, continued on in command of a Corps…)

You could call Leonidas Polk a “reluctant leader” (he submitted his resignation on at least two occasions, but Jefferson Davis refused to let Polk go.)

Mike,

That is a good defense of Polk, who to be fair does suffer from whipping boy syndrome. I think Polk was undermined by serving under Bragg as Bragg was by having him in corps command. The two detested each other and it hobbled the army and each other; Polk did better when away from Bragg. Davis needed to separate them after Stones River, and his failure to do so is his most baffling personnel decision of the war.

Interesting abd valid points regarding Polk’s initial activities but I don’t think that they offset a few important facts. (1) Polk graduated from West Point and resigned his commission within months. His appointment in 1861 was based on virtually no military experience. (2) His performance at Perryville left much to be desired. (3) He spent much of his time politicking against Bragg. For a balanced and competently-written assessment of Bragg, I recommend Earl Hess’s recent book. (3) Polk’s performance throughout the Chickamauga campaign was mediocre to poor. He seems to have spent most of his time figuring out how to defy Bragg. (4) Nothing he did during the Atlanta Campaign until his death stood out. I can’t honestly say that his performance at Resaca, which included a questionable and bloody decision to try to retake lost ground, is much different from the rest of his track record. It’s hard to see how the CSA lost a whole lot with his demise.

doing better is relative, and as you point out Polk did not exactly impress in previous battles. He does seem to have been at his worst though under Bragg.

The “reminder of the falsity of presenting the Confederacy and Nazi Germany as equivalences” does not erase the equivalency of the principles of racism and untermenschen.

The equivalency argument does ignore the fact that Nazis are hardcore totalitarians and the Confederates believe in republican government with checks and balances.

By the same token, Hitler was on record praising America’s conquest of the west, which was carried out by the same Union generals who beat the South, who themselves mostly believed they were “untermenschen” in relation to non-whites. At any rate, I have never read of Hitler praising the Confederates, and likely because he found state’s rights and faux-aristocrats abhorrent. Racism at the time was so prevalent, he did not have to resort to the Confederates to find examples.

It is a dangerous game to play up similarities between things we do not like and ignore the differences.

The dangers, of course, are a two-way street. For example, Goebbels (whose job was to express official viewpoints) raved about “Gone With the Wind” when it hit Germany in 1940 and Mitchell’s book already had seen massive sales in Germany. Hardly conclusive but Goebbels likely wasn’t into the acting or the staging as a movie critic.

It would be interesting to look at reactions to Gone with the Wind in other countries. While we are sometimes quick to go in for explaining the film’s success as due to racism, I will add a few thoughts as a film buff who used to direct movies.

The film is superbly shot, with lush colors, some superb performances, and one of the era’s best film scores. It also had an appeal to people still living in the shadow of World War I and the Great Depression. When Scarlett says “God as my witness I will never go hungry again!” that was powerful stuff for people for whom bread lines and the Dust Bowl were current events.

I don’t disagree. But Goebbels hardly had a reputation as a movie critic and I’d lay odds against his appreciation for cinematic art (although I’m sure he liked Leni Reifenstahl’s work) . There’s little question that the book and the movie convey a racist viewpoint, although it’s not central to the movie. Your point about the Depression is well taken but that also occurred in what was still a society that tolerated racism . We know that none of the blacks who acted in the movie were able to attend the premiere in Atlanta. The movie had none of the blatant, violent material that Griffiths dumped into Birth of a Nation – it was much subtler.

Funny you mention that about Goebbels. His diary is filled with movie opinions. He is not writing Truffaut level criticism, but he has opinions, and they are often technical. He also oversaw the German film industry, most infamously ordering a Titanic movie that features a German officer trying to warn the British about icebergs.

Gone with the Wind is more resilient than other films because it is first and foremost a love story, and well done in terms of craft. That said, its stock will likely continue to fall, until it is seen mostly as a historical artifact.

As to the depression and the racist society, my point is the movie’s popularity had to do with with technical and artistic touches, as well as the backdrop of the Great Depression. That said, it was a racist society, and therefore the film’s racism was not only tolerated, but likely seen as being more benign than other films. More to the point, it was not popular because it was racist.

The swastika is an ancient symbol of all major religions with a prominent place in Christianity. It, along with the “Roman salute” (previously practiced by Americans when addressing the flag) and naming your male sons Adolph, went the way with Hitler and Nazi Germany. If anything the artist is guilty of just poor timing. Fortunately our forefathers were not part of a cancel culture and decide to destroy the window.

As far as the swastika goes, it was considered a good luck charm or symbol centuries before the nazis compromised it. A U.S. national guard unit from out west even had it on their unit patch pre-war. That may have been what the crafter of the dragon was thinking and not sympathy for nazi Germany.

Highly unlikely since it is St. George killing the dragon and the dragon has the swastikas on it. Also it was made in 1939.

Legend has it, unless Im mistaken, that General Sherman was involved with aiming the cannon fire that killed General Polk. One source said that he had the particular cannon fire and elevated so that it would strike near, if not on, the site where General Polk was standing.

It is possible as he did aim some cannon at Atlanta, but seems unlikely. I have also heard it might have been Captain Hubert Dilger Dilger of Battery I 1st Ohio Artillery.

The version which seems most reliable has the Fifth Indiana acting on the direct orders of Capt. Peter Simonson, who was chief of artillery in Stanley;s division of the IV Corps. The orders apparently originated with Sherman and went to Howard. Ironically, Simonson was killed by a sniper two or three days later, IIRC.

Sherman had good reason for animus toward Polk: Forrest at Okolona.

He was not an “Arch Bishop.” He was the Bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Diocese of Louisiana. The National Episcopal Church does have a “Presiding Bishop,” but not an Arch Bishop.

He was indeed Arch-Divine, though.

Bishop Stephen Elliott, his eulogist, was the Presiding Bishop of the Confederacy.

He was brought to New Orleans in 1944, put in the holding vault at Metairie Cemetery, then reinterred in Christ Church Episcopal Cathedral Shrine in 1945.

Do you know which tomb was the holding tomb? Perhaps the Army of Tennessee Tumulus?

I went by what I was told at the church in terms of when his body was moved, so thank you for correcting that.

There is a separate, large open air vault near the AoT.

He was there, not AoT, which is for permanent burial.

From google maps earth view, it is the white building immediately catty corner across from AoT walkway and looks like a chapel.

Lost Cause “mythology” recognizes the indespensible significance of his battlefield successes, particularly how, under his direct orders, General Forrest ruined Sherman’s Selma Campaign with a decisive victory at Okolona.

Describe the next inevitability that would have followed from Sherman’s cavalry from Memphis joining him at Meridian, then admit that whatever bad for the Confederacy would have then marched eastward toward Selma, Montgomery, Tallassee, Columbus, Macon, Augusta, and Columbia, was a bad that Polk had stopped.

Polk’s service to his nation was one of prevention and extension. Where’s the myth?

Sherman did not have a Meridian Campaign. He made it only as far as Meridian, because of Polk and Forrest. Where’s the myth?

He saved Johnston twice at Resaca, then at Cassville, then, even after his death, his contribution of the Army of Mississippi as a third corps to the Army of Tennessee within Atlanta’s city fortification was still enough to prevent Sherman from ever taking Atlanta by direct assault.

Look at his record, subtract his contributions, and join the growing awareness that his efforts alone prolonged the chance of a Gained Miracle for the Confederacy.

Where’s the myth?

“check out Polk’s resting place”

The Shrine of Bishop-General Leonidas Polk is not something that one “checks out.”

Please elevate the attitude to match the requirement.

“undermine our concrete views”

Polk’s legacy is immune to Critical Theory. He does the De-Constructioning; he is not deconstructed.

When you visit the restored and reopened Atlanta Cyclorama next year at the Atlanta History Center, thank the Bishop-General.

The painting dramatically presents the moment when Manigault’s Rebs had broken through and pushed back Lightburn’s Yanks to the farthermost backward point of lost territory.

This chance for Confederate victory east of Atlanta was possible only because Polk’s Army of Mississippi, then renamed Stewart’s Corps, was occupying the attention of enough of Sherman’s army elsewhere around Atlanta that the XV Corps’s weakness was exploitable by Cheatham.

“Dirty Work” Logan, brave and victorious battlefield hero that he was, restored the line and rescued the Yanks.

You see him charging to the front in the painting. You see him charging to the front while carrying Reb-inflicted wounds from Donelson that would eventually kill him in 1886 and prevent his election to the White House in 1888.

Lost Cause mythology calls those wounds and his fate the “Jefferson Davis’s revenge.”

But is it Lost Cause mythology that asks how Logan, a Yankee general at war against Treason and Disunion, somehow made the equivalent of $2,000,000 in today’s value in “land sales” in Georgia just prior to the Atlanta Campaign?

What was a Yankee general doing speculating in Confederate real estate for profit when he was at war with the Confederacy?

Did the Yankee Gilded Age begin in Northwest Georgia in 1864, instead of up North in 1870?

Yes, let’s undermine some “settled history.”

If racism and a belief that non-whites are inferior equates support of National Socialism then all Nineteenth Century Caucasians in the Western World will have to be condemned. These were the accepted points of view held by the vast majority on both sides of the Atlantic.

I will venture to expand on Michael Bradley’s excellent post: to suggest that Leonidas Polk was somehow responsible for the writing of “Gone with the Wind,” is ridiculous. And to allude that someone who died in 1864 “was a NAZI” is beyond the pale.

We can do better in our arguments, and our expression of viewpoint without resorting to Character assassination. Please keep Mao and Pol Pot and Hitler out of the American Civil War.

Also, “Polk’s Resting Place” is problematic.

He’s not resting.

I have studied Polk extensively due to a myth that has been perpetuated for over a century that he went to school in Seaford, Delaware. Former Confederate J. Thomas Scharf published a History of Delaware around 1890 and stated in one sentence that Polk had attended the Seaford Academy, “for a time.” Scharf received unverified input from throughout the state in compiling his history. There is nothing in the family’s history to support the story. My article from Delaware History magazine is on-line at Academia.com