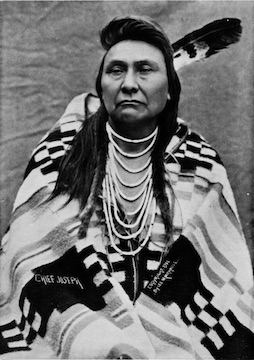

Chief Joseph: If not for Howard, “there would have been no war”

My favorite description of Oliver Otis Howard comes from historian Frank O’Reilly, who has called him “pious but vapid.”

My favorite description of Oliver Otis Howard comes from historian Frank O’Reilly, who has called him “pious but vapid.”

After the twin disasters that befell Howard’s Eleventh Corps at Chancellorsville and then, two months later, at Gettysburg, it’s always been a bit of a wonder to me that Howard managed to keep his job. I suppose his credible defense of Cemetery Hill alongside Winfield Scott Hancock helped keep him in the ballgame, although it didn’t save him from banishment to the Western Theater.

But even that perspective deserves rethinking. After all, the West was where the Union was generally winning. Yes, troublesome Confederate generals usually got shuffled westward, but it’s harder to make the case for outright banishment with Howard and his men. Chickamauga and the siege of Chattanooga had reversed and then stalled the Union war effort, and Lincoln needed to get it back on track. One doesn’t do that with crappy troops.

Howard served credibly out West, eventually even rising to army command. For that reason, I’ve always thought of him as “Keep Your Head Down” Howard (rather than the more traditional “Uh-Oh” Howard that plays off his initials and his twin disasters). Because of his skill at keeping his head down, and despite his twin debacles, Howard went on to a long, successful career in the army—highlighted perhaps most famously by events on this date in 1877.

I’m not going to pretend to be an expert on the Indian Wars, but I do know Howard was in the thick of them. In 1877, when the Federal government tried to force the Nez Perce tribe from their ancestral homeland in Oregon to a small reservation in Idaho, a band of about 700 of them, led by Chief Joseph, resisted. Howard, initially sympathetic to the Nez Perce’s concerns, nonetheless attempted to bring them to bay.

Chief Joseph said he did not believe “the Great Spirit Chief gave one kind of men the right to tell another kind of men what they must do.” Howard took Chief Joseph’s words as a challenge, but Chief Joseph sought to avoid war by instead leading his people toward sanctuary in Canada.

Chief Joseph said he did not believe “the Great Spirit Chief gave one kind of men the right to tell another kind of men what they must do.” Howard took Chief Joseph’s words as a challenge, but Chief Joseph sought to avoid war by instead leading his people toward sanctuary in Canada.

Howard pursued. The result was a five-month, 1,170-mile series of running conflicts—the Nez Perce War—which Howard characterized in his memoirs as “the most arduous campaign.” Each time Howard’s troops tried to wrangle the Nez Perce, the Nez Perce skillfully fended them off.

Exceptionally frigid weather, moreso than just the Federal pursuit, finally put an end to the chase. Unable to get past General Nelson Miles’s infantry or Howard-led cavalry, running low on food and supplies, and suffering in sub-zero temperatures, the Nez Perce surrendered. Howard, though, took the credit: “through my own interpreter [I] succeeded in persuading Chief Joseph to abandon further hostile effort and make a prompt surrender,” he wrote in his memoirs.

Popular history remembers Chief Joseph’s words thus:

Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have it in my heart. I have it in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed; Looking Glass is dead, Too-hul-hul-sote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led on the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets; the little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, to see how many I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.

Chief Joseph’s statement—probably not written by him—has become apocryphal. After all, who can resist a sentiment like “I will fight no more forever.” Certainly not America. Chief Joseph became a national celebrity, although he ultimately died far from home.

Howard, for his part, argued that the Nez Perce had been treated unfairly from the get-go, even if that didn’t prevent him from leading forces against them. Chief Joseph place blame for the entire conflict squarely on Howard’s shoulders. “If General Howard had given me plenty of time to gather up my stock and treated Too-hool-hool-suit [another Nez Perce leader] as a man should be treated,” he said, “there would have been no war.”

History has largely remembered Chief Joseph as a military genius—a perception that, as I understand it, Howard promoted. After all, if his opponent was wily and skillful, that would better excuse Howard’s difficulty in running him down.

Howard lived until 1909, which gave him decades to tell his side of any story his way, usually well after other characters had died away. His mammoth two-volume autobiography tops out at almost 1,300 pages. For a guy who largely survived by keeping his head down, that’s an awful lot to say.

It also helped that he served as director of the Freedmen’s Bureau, superintendent of West Point, and founder of Howard University, among other achievements, and he rose all the way to the rank of major general in the regular army (his major generalship during the Civil War was of volunteers). The French also named him to their Legion of Honor.

And so, if Howard was treading the water of history, and Chancellorsville and Gettysburg were two lead weights tied to his ankles, all this other stuff has been just enough to let his legacy keep grabbing gasps of air instead of getting dragged to the murky bottom.

All of which is to say that there’s more to consider about Howard than just Chancellorsville or Gettysburg, even he’ll never be free of those debacles.

I wouldn’t diminish Chief Joseph’s reputation simply because Howard’s accolade might in part be self-serving. He conducted a retreat which Nathaniel Greene would have admired, covering some one thousand miles and involving skillful tactics on several occasions.

Good point, John, and I don’t mean to do so. I was just trying to make the point that Howard found it a convenient excuse to cover his own shortcomings.

I just picked up “Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War” by Daniel Sharfstein so I can delve more deeply into this topic. As I admitted, I’m no expert on any of this!

Chris: No problem. I have actually heard somebody say that before so I’m attuned to it. And I have little doubt that “Otis” could well have been happy to use it for his own purposes.

By the way, for a contrarian view of Joseph and his role, you might want to access the book by Kent Nerburn. Not without its own issues but it does present a different perspective. I haven’t read the Cozzens book.

So nice to read ECW this morning. I really appreciate it when we look at the people who gave four years of their lives to the Civil War but actually did much more when an entire life is examined. I would not call a man who seemed to have had the concerns of others always in his mind as “vapid,” however. Anyway–thanks for this morning read.

Meg: The troops of German ancestry who were victimized by the ineptitude of Howard and some of his subordinates (Devens and Barlow) at C’ville and G’burg and who were disparaged by them as unreliable “Dutchmen” might (justifiably) disagree.

Very good article. My father hated Howard for running down the Nez Pearce ad considered him a hypocrite. I think that is a tad too simplistic. At any rate, Howard was able to gain the trust Of Sherman, who had the trust of Grant, thereby assuring his place the army high command during and after the war.

I have traversed much of the territory Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce followed in 1877 through Idaho, Montana and Wyoming. They lead Howard on a merry chase through some very rugged country. I do not think Howard was any match for the Nez Perce of Joseph.

But O.O. did chase him down.

I think you may be holding Howard responsible just for following orders. Remember, the Nez Perce removal from Oregon began in May 1877, barely 10 months after Little Big Horn. The disaster hardened the hearts of Sherman and Sheridan, for sure. There were 2000 Sioux and Cheyenne warriors just over the border in Canada, hiding from the US Army. If the Nez Perce band (which never had more than 250 warriors and at least 500 women, children, and old men, and 2000 ponies) could defy orders to go to the reservation, and the Army was unable to enforce this order, the credibility of the Army was in jeopardy. And Howard was not the only US officer to follow orders to get the Nez Perce back to the reservation. Nelson Miles finally cut them off 40 miles from Canada.

And when Sherman dishonored the pledge that Miles gave to Chief Joseph, that they would go to Idaho to join the Nez Perce already on the reservation, and sent them to Oklahoma instead, both Howard and Miles protested.

John Gibbon’s command engaged them at Big Hole as well.

Sherman and Sheridan didn’t need the Little Big Horn to harden their hearts – they were already there.

can’t stand howard, never could. a pious pompous insufferable ass. telling meade that the first corps broke first at gettysburg !

Can you give a citation where Howard told Meade First Corps was the first to break?

Joseph had insisted the Walla Walla Valley was sacred to his people. Howard would have given them the valley as a reservation if Joseph would pledge stay there. He would not. Then, when Joseph says he’ll bring his people to Lapwai, having personally ridden with Howard to select the tract, as O.O. is waiting for their promised arrival the Nez Perce go to slaughtering settlers. So, of course, Howard goes after him. Joseph was a master of passive aggressive behavior and the idea that he just needed more time is really disingenuous.