Thoughts on “Madame Castel’s Lodger”

New Orleans has produced a fair number of notable authors, in particular George Washington Cable, John Kennedy Toole, and Anne Rice. However, it is more famous as the inspiration for writers of the first rank: Thomas “Tennessee” Williams III, William Faulkner, Mark Twain, and Truman Capote to name but a few. Its unique cultural mixture attracts people looking for something different. Many are drawn to whatever is en vogue, given whatever the era’s proclivities might be.

New Orleans has often changed how it sells itself to the world. Before the 20th Century, it was gambling and commerce. Today, it is culture, whether it is food, music, architecture, or the night life. I was born in 1982, during the transition away from the city selling itself as the Creole version of the Old South and towards a depiction of the city as a Cajun outpost. Atlanta sold Gone with the Wind memorabilia, but we sold steamboat cruises, plantation tours, and antebellum artifacts. This is when the Garden District became a major tourist attraction. The wellspring of this type of history was Grace King, who during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, wrote about grand Creole families. Whatever her faults, King is a wealth of anecdotes and family trees. The descendants of the great founding families such as Marigny, Toutant-Beauregard, de la Ronde, Villeré, and the rest draw much of their family knowledge from King. For many, this was the “real” New Orleans.

This era was epitomized by the novels written by Virginia native Frances Parkinson Keyes. She was one of the first popular female authors of the twentieth century, and counted Franklin Roosevelt among her fans. She wrote some sixty novels, memoirs, and travelogues from 1918 to 1970. Many of them were about New Orleans. In 1944, she bought a fine French Quarter home at 1113 Chartres Street that was the postwar lodging of P.G.T. Beauregard. She renovated it and made sure it would operate as a museum after her death. Today, it is the Beauregard-Keyes House.

Keyes was obsessed with Beauregard’s story and in the 1940’s started writing a novel about his life. In 1962, Madame Castel’s Lodger was published to positive reviews. It represents one of the last literary blushes of the Lost Cause mythology.

There is hardly a plot in Madame Castel’s Lodger. Beauregard returns from the war and rents a room from Simone Castel. They are attracted to each other but do nothing about it; Keyes was a moralist at heart, although given to romantic flourishes. Instead, Beauregard recounts his life to various people in a strict chronological order. There is a fictional subplot about Beauregard trying to find Lance Castel, a soldier in the Orleans Guard Battalion who has been missing since Shiloh. Lance is found but it is a moment wholly lacking in drama.

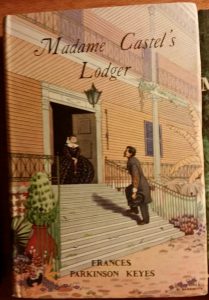

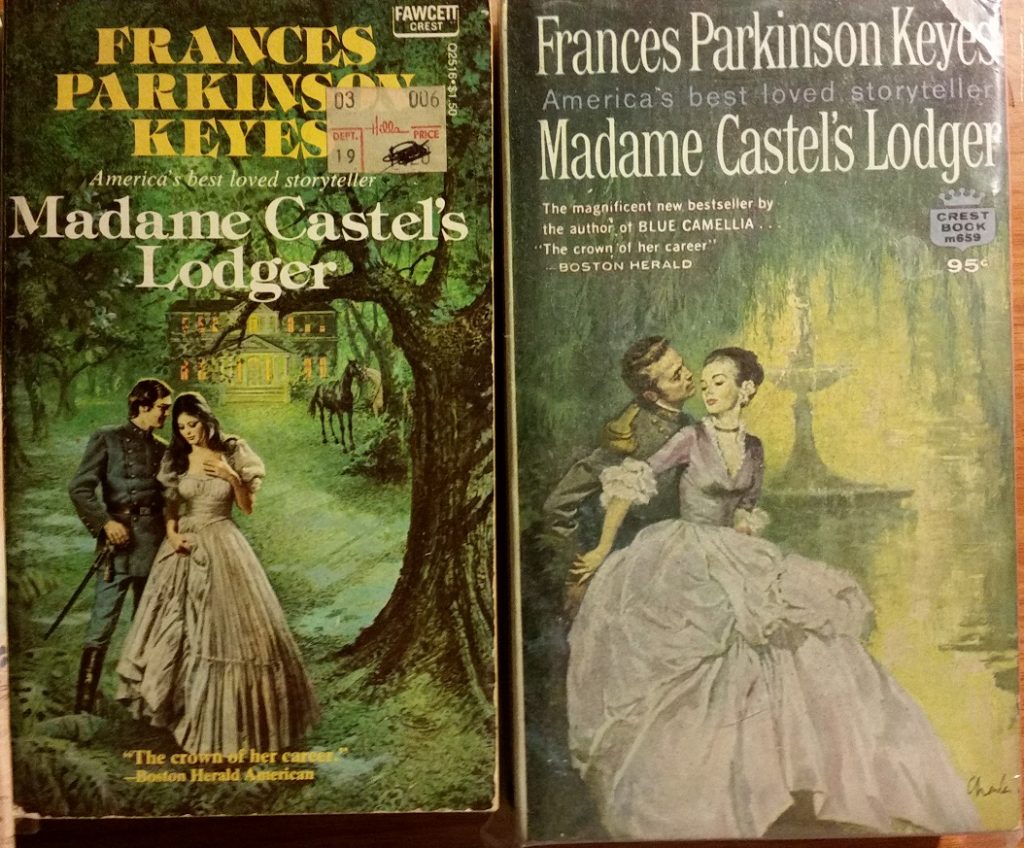

The book’s lack of drama can be seen in the book covers, which often contradicted the narrative. The American hardback simply showed the house. The British edition showed an incorrect house but depicted one of the best scenes in the book, when Beauregard comes to seek lodging. Paperbacks depicted scenes that never occurred: steamboats, carriage traffic jams, and even moss covered romantic meetings with a Confederate officer who looks like Ashley Wilkes. Just try to imagine Beauregard blonde and clean shaven.

The Lost Cause elements are of the moonlight and magnolias variety. Indeed, Keyes even has Beauregard defending this, saying it was real and not a myth. Issues of race and slavery are dodged. The central Lost Cause facet is the idea of rebuilding Southern society after the war, in this case getting a job. Gone are the politics and the tumult, replaced with a dull subplot about getting employment. Beauregard’s internal debate about whether to ask for a pardon, which he grappled with, is mostly missing. On the better end, Lost Cause villains Benjamin Butler and William Tecumseh Sherman are portrayed in a more complex light.

It might seem cheap to dismiss the book’s limitations from our vantage point; my main issue was the lack of plot, for it is mostly a kind of Beauregard biography. The ideas of memory and loss are explored but not in depth. Where the book is of some interest is Keyes’s attention to detail. Her sense of Louisiana geography is superb, no minor thing for me. I was raised on Hollywood movies where New Orleans is just the French Quarter and the swamp, with nothing in between. Keyes loved romance and old Creole families and those are best parts. Her attention to detail in this regard is superb and I actually learned some family lore from the novel. Keyes was friends with Beauregard’s granddaughter, Laure Beauregard Larendon, and repeated some family stories. Keyes’s mistakes are more apparent in recalling Beauregard’s military career, but even then they are more minor than damning. Keyes is also good for finding graves and plantation names. She even copied some letters and grave inscriptions that are today so worn down as to be unreadable.

Unfortunately, Keyes did not get to the heart of the matter. She was perceptive in understanding Beauregard’s dreams but not his limitations. His personal blemishes are absent. He was not kind to the memory of his second wife, Caroline Deslondes. He was deeply jealous of Robert E. Lee. He could be exceedingly petty and mean, and in Madame Castel’s Lodger he is neither. He is instead a nearly perfect Creole gentleman, undone by fate more than his own hand. Both of his wives die, Louisiana secedes, and he runs afoul of Jefferson Davis, and in each case he has no choice in the narrative. In reality, he did. He could have been better to Caroline, stayed loyal, and not feuded with Davis. All of this is the stuff of tragedy, of a talented man making bad or at least difficult choices. Keyes instead went in for melodrama.

Keyes’s Creole Old South is almost gone as a part of New Orleans’ popular memory. In her day, the emphasis was on powerful Creole families made up of grand eccentrics who could recall off-hand, their European lineages, mostly French and Spanish, with the occasional person from England, Portugal, Belgium, and Italy finding their way into the family tree. This was not the world of Anglo-Americans coming to make money, nor that of poor Irish, Germans, and Italians who streamed into the city. Most importantly, it was a version of Creole life divorced from its African influences and blood relations. For Keyes, King, and the rest the “real” New Orleans was a white Creole past that emphasized the colonial era. Today, New Orleans sells itself in part as a center of African-American culture. One person I know designed a shirt that says “everything you love about New Orleans is because of black people.” We sell ourselves not as a Southern city or one on the outskirts of Cajun country, but as the “northern most Caribbean city.”

King and Keyes have their uses and their limitations. If they fundamentally erred, it was in thinking they knew the “real” New Orleans. Today’s historians and artists often mock King and Keyes. I have heard many tour guides scoff at King as saccharine and privileged. Keyes is all but forgotten except for the odd reference to her only work still in circulation, Dinner at Antoine’s. They are ignored, while others pursue a new version of the “real” New Orleans, one that will inevitably be eclipsed by another type of authenticity we sell to ourselves and the world.

Those covers certainly do reflect a “magnolias and moonlight” image of Beauregard, don’t they!

There are few scenes that are like the cover above, but of course Beauregard and Laure looked nothing like the two on the covered. Should be noted these were for the paperback market.

Amazing! With all the new titles being published in the Civil War genre, I still love to read old stuff. I will be ordering this immediately! More!! Please!! Doesn’t the Union have something? Thanks for this, by the way.

Ever read Judson Kilpatrick’s “Allatoona: An Historical and Military Drama in Five Acts?” It is a very partisan work that used in a paper about how Union generals remembered the Civil War.