The Inaugural Express: Abraham Lincoln’s Train Journey from Springfield to Washington

One of my favorite trains—and there are several—is the Inaugural Express, the series of trains taken by President-elect Lincoln as he made his famous journey from his home in Springfield to the Executive Mansion in Washington. Standardization of track sizes was not a law in 1861, so Lincoln was forced to change trains several times on his journey. This created an informal contest among cities and train companies to provide the most extravagantly decorated, patriotic, comfortable, and fast train ever imagined, and descriptions of the results are amazing.

Much has been written about the train the presidential party boarded in Springfield. Here is a personal version:

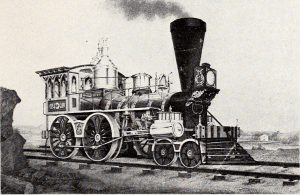

By 7:30 AM, everything necessary for the inaugural journey was packed on the exquisitely designed, private, three-car train waiting at Springfield’s Great Western Depot. The engine was a modern marvel of gleam and steam, hissing in readiness with its smoke-retarding funnel stack towering over the huge crowd of well-wishers bundled up against the weather to see President-elect Abraham Lincoln off on the first leg of his journey to Washington. A baggage car followed the steam engine. The last part of the small train was a yellow passenger car, its wooden trim varnished to brightness, and its sides so brightly painted that it shimmered out amid the steamy mist, festively draped with bunting and hung with flags. Secretary John Nicolay wrote that the “stormy morning” added “gloom and depression, subdued anxiety, almost of solemnity . . .” to their departure.[1]

The National Park Service did a reenactment of the event, which can be viewed at

https://www.c-span.org/video/?298139-1/president-elect-lincolns-inaugural-train-trip. Lincoln is admirably portrayed by Fritz Klein, but there was little effort to accurately portray Lincoln’s small party of friends and supporters, which included Elmer Ellsworth.

When Lincoln’s train crossed the state line into Indiana, the train cars were linked to a new engine that was compatible with the Toledo and Wabash track gauge, which was of a different size than the one they had previously traveled. Lincoln marveled at the speed of the train–up to thirty miles an hour–and by 5:00 PM they arrived at Indianapolis. In the state capital, the crowds gave Lincoln his most impressive welcome yet. The cheers were deafening. “Apparently,” wrote John Hay, “the entire population of Indianapolis and the surrounding territory,” were in attendance, “and its enthusiasm at fever heat.”[2]

When the Lincoln party arrived at the Indianapolis depot, another new engine was waiting for them. To the delight of Willie and Tad, it was a gleaming, impressive piece of machinery, draped with flags and bunting. The smokestack was embossed with thirty-four white stars. Lithographic portraits of every president before Lincoln lined its sides. The entire party left Indianapolis, Indiana at about 11:00 AM, bound for Cincinnati.[3] A fourth engine, bedecked with flags, shining within its cocoon of steam, was waiting for the Lincoln party on Thursday morning, February 14, at the Columbus train depot. The Lincolns traveled through Ohio, waving at the people standing by the track, and slowing down at Cadiz Junction to receive a carefully wrapped, elegant dinner from the wife of the president of the Steubenville and Indiana Railroad.[4]

This was the train configuration the Lincoln entourage rode until it reached Albany, New York, on February 18. The train pulled into Albany, the capital of the state of New York, at 2:30 in the afternoon. John Hay described the journey in three words: “Crowds, cannon, and cheers.”[5] By 7:45 the next morning, yet another new train chugged out of Albany. Because it was going to be arriving in New York City, the train carrying the President-elect and his party was the most opulent, the most gilded, the very best of excessive Victorian styling that the Union had to offer. From the beginning of the journey, each railroad company had tried to outdo the one before it in the speed, comfort, and looks of its train. The one that took Lincoln to the “Empire City” was an amazing compilation of every art that could be brought together to create a steam locomotive. The passenger car was shellacked with orange spar varnish, giving the oak a soft golden glow. The exterior of the car was ornamented with curling Victorian flourishes painted in black and brown. National flags, bunting, streamers, and ribbons decorated it as well. This magnificent traveling hotel was pulled by two modern, powerful steam locomotives–the Union and the Constitution–and more than five hundred railroad employees were working all along the line to be sure the Lincoln party arrived at the Hudson River railroad terminal without incident.[6]

These two engines pulled Lincoln’s train to Philadelphia, where they arrived on February 20, an auspicious date for the Inaugural Express. Supper was scheduled at about 7:00 PM, and at 9:00 the same evening Philadelphia celebrated Lincoln’s election with a glorious show of pyrotechnics. The grand finale of the fireworks show was a static display of grandiose proportions. Within a red, white, and blue wall of fire, silver letters forming the words, “Welcome, Abraham Lincoln. The Whole Union” were illuminated.[7] About an hour later, most people thought the fireworks were over, but in truth, they had just begun. Norman Judd had urged the President-elect to attend a secret meeting after the fireworks had faded from the winter skies. Judd explained that he had been in close contact with detective Allan Pinkerton whose company, the Pinkerton Detective Agency, had been hired by the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad to investigate a plot to do damage to railroad property during Lincoln’s stop in Baltimore.[8] Not long into the investigation, the Pinkerton team had uncovered a far more sinister plot.

Pinkerton told Lincoln and several others that Calvert Station in Baltimore had an odd configuration. To get from the inbound trains to the outbound trains, one had to pass through a narrow pedestrian tunnel. Lincoln would have to travel by carriage through the same tunnel to get to the Eutaw House, where he was to stay in Baltimore. Southern sympathizers had plotted to create an altercation down the tracks from Lincoln’s train, which would draw the Baltimore police away from the tunnel. When Lincoln’s party entered the tunnel, at least eight men were to be ready to either stab or shoot the President-elect.[9]

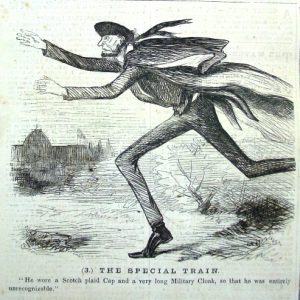

Pinkerton then explained the outlines of his plan to get the President-Elect safely into the capital, but it would involve leaving the beautifully decorated Victorian steam leviathans and traveling in a plain, public conveyance. Lincoln was told that a one-car train would be waiting in Harrisburg to take him back to Philadelphia, where he would board the regular Pennsylvania, Washington, and Baltimore train for Washington at 11:00 PM. Lincoln, accompanied by Ward Hill Lamon and Kate Warne, one of Pinkerton’s female operatives, would be disguised in a soft felt hat and a “man’s shawl” of tartan plaid, stooping and appearing frail.[10] Mary Lincoln and the rest of the Lincoln party continued to Baltimore, then on to Washington, but no one really cared much about the train anymore. Tad and Willy probably still enjoyed the steamy sparkles on all the gold and gilt, but they were not informed about their father’s “complications.”

The Inaugural Express in all its iterations was the finest tribute the North and its burgeoning railroad industry could make to the incoming executive, and although images of the trains are few, they must have been magnificent. Each engine was an important part of the celebration of Union. The train Lincoln would ride back to Springfield, a mere four years later, would be equally important if not nearly as glorious.

_________________________________________

[1]John Hay and John G. Nicolay, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, 10 vols. New York: The Century Company, 1880.

[2]Michael Burlingame, ed., Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press, 1860-1864, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1998.

[3]Brian Wolly, “Lincoln’s Whistle-Stop Trip to Washington,” February 9, 2011: Smithsonian.com.

[4]New York Times, February 15, 1861

[5]John Hay, diary, undated.

[6]New York Herald, February 20, 1861.

[7]Ibid.

[8]Allan Pinkerton: The First Private Eye by James Mackay, and Lincoln’s Spymaster by Samantha Seiple.

[9]Daniel Stashower, The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War, New York: Minotaur Books, 2013.

[10]Ibid.

Meg

Thanks for giving us a closer look at Lincoln’s Inaugural Express. I was aware of the significant gaps between stations inside Southern cities (requiring wagons or other transport to get from one train line to another, up to a mile away) but had no idea the North suffered from the same lunacy. Baltimore, being a Southern city inside a Border State, took proactive measures, first to deny Lincoln the Presidency; then to prevent Northern reinforcements from using the only rail line connecting the Northern States to the National Capital at Washington City. In arguably the most significant feat of his Civil War career, General Benjamin Butler circumvented the torn up tracks at Baltimore, and made use of steamboats to bring his Massachusetts troops south from Philadelphia to Annapolis, rebuilt damaged bridges, and got the reinforcements through to the Capital (restoring HOPE, after a week of uncertainty whether Washington could hold out, seemingly surrounded by unfriendly, shadowy forces in Virginia and Maryland.

Butler is seriously underrated. His politicalcareer prior to the war is pretty impressive, and his service to the Union continued after the war as well. One or two battlefield “situations” does not complete the measire of the man. And thanks for your comments as well.

In January 1861 S. M. Felton, chief of the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore R.R. learned of “a deep-laid conspiracy to capture Washington, and destroy all avenues leading to it… and thus prevent the inauguration of Mr. Lincoln in the Capitol of the country” [from Smithsonian.] Lincoln set off from Springfield on his rail journey, and the first “unusual occurrence” was encountered near the Indiana/ Ohio border: a piece of rail equipment was discovered lying across the track by one of the Inaugural Train’s pilot engines, sent ahead to clear the track. To this day, it is unknown whether the equipment was left intentionally or by accident. [Although secessionists afterwards referred to “an effort by Lincoln to avoid a plunge of his train down an embankment” and this could not have taken place at Baltimore.]

The next unusual occurrence happened a few days later and involved a piece of luggage left under a seat in Lincoln’s passenger carriage. It was quietly removed: some afterwards claimed it was a bomb; others declared it was nothing.

Meanwhile, Allan Pinkerton had been contracted by railroad chief Felton to provide security for Lincoln’s Inauguration Train. Pinkerton had agents in Baltimore that uncovered a viable plot against the President-elect; and this same plot was detected by agents working for William Seward. Seward’s son, Frederick, delivered a letter from William Seward to Lincoln which seemed to confirm Pinkerton’s information. The President-elect adjusted his travel plans and avoided any potential unpleasantness in Baltimore. [Despite popular claims that “it was only Lincoln’s imagination, making him look foolish,” Louis Wigfall later revealed the identity of the man who led the Baltimore Plot against Lincoln.]

arama motoru, son dakika haberleri, nöbetçi eczaneler, hava durumu , kripto para fiyatlar?, koronavirüs tablosu, döviz kurlar?, akl?na tak?lan her ?eyin cevab? burada

To find the best consulting agency UAE for your business, look no further than Business Consultant UAE. We are a leading management consultancy in Dubai, with an extensive list of services to choose from.

Whoever monitors this site, please remove all business ads.

Did Lincoln’s trains have telegraphers?

The railroads involved furnished telegraphers who rode the train and they also had portable equipment if needed.

Who paid for the inaugural train trip and what did it cost?

The map is inaccurate as West Virginia was not a state at the time of Lincoln’s trip to Washington