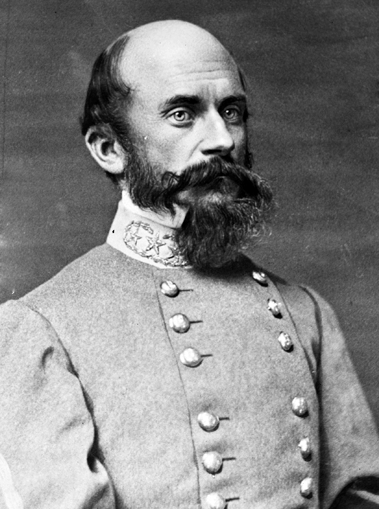

The Next Stonewall? Ewell and the Second Battle of Winchester, Part 1

Richard S. Ewell may be one of the Confederacy’s overlooked and overshadowed infantry corps commanders. By the time he took over the Second Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, there were big boots to fill; following in “Stonewall” Jackson’s footsteps was not easy. Still, during the Gettysburg Campaign, Ewell scored a major victory and his troops and the local civilians genuinely believed he was the next legendary general for the Second Corps and the Shenandoah Valley.

What went wrong? Why does Ewell usually fall in the category of forgotten corps commanders? And what did he really accomplish at the Second Battle of Winchester – arguably one of his finest military moments?

According to my observations, Ewell fell out of popularity in memory and history for five major reasons. First, he was not Jackson, and “Stonewall” had a legacy and legend that choked out successors. Second, Ewell became one of the Gettysburg scapegoats despite a magnificent showing from his corps on July 1 and heavy fighting on July 2 and 3; Culp’s Hill is a lesser-known part of the battle, and both Lee-defenders and pop-culture found Ewell an easy target for not attempting to secure Culp’s Hill in the first evening. Third, Ewell squabbled with his staff officers, particularly in the autumn of 1863; they were already inclined to compare him to Jackson, and when he failed to take initiative and then seemed to let his wife run headquarters, he managed to alienate the officers who could have been his best fan club and memory defenders. Fourth, Ewell struggled with health issues; his amputated leg did not heal properly, and by May 1864, he asked to be relieved from active duty, factors which may have limited his effectiveness during his later field campaigns. Fifth, Ewell is bookended by two very colorful characters of corps command – Jackson and Early, aka “Stonewall” and “Lee’s Bad Old Man”; it’s easy to skip over Ewell, but he was a really interesting character, too – just “Old Bald Head” is not as cool of a nickname as his predecessor or successor.

However, many of those troubles for Ewell and how he would be remembered were not factoring into his actions and experiences during the early part of the Gettysburg campaign. We have to peel back those lenses and see this remarkably interesting man as his officers and men saw him on those hot June days when he orchestrated and scored a smashing victory at Winchester.

Richard Stoddard Ewell – forty-six years old during summer 1863 – had graduated West Point, fought in the Mexican-American War, resigned his U.S. Army commission, and joined the Confederacy as a brigadier general in June 1861. By January 1862, he promoted to major general and fought – reluctantly at first – with Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley and Seven Days Battles. At Second Manassas, he was badly wounded left leg and suffered an amputation shortly after; during his recovery, Ewell “got religion” and married his cousin Lizinka Campbell Brown, a wealthy widow from Tennessee. When he returned to the army shortly after the wedding, Ewell’s men noticed a change in his behavior and wondered if their general could still fight after his injury, new found faith, and marriage. As they soon found out, Ewell had a steady focus and determination to win during this campaign.

Ewell’s Chief of Staff, Major Alexander S. Pendleton explained in early June:

“The more I see of General Ewell the more I am pleased with him. He resembles Gen. Jackson very much in some points of his character, particularly his under disregard of his own personal comforts & his inflexibility of purpose. Yesterday he rode 20 miles on horseback, often at full speed & exhibited no signs of fatigue last night. He is so thoroughly honest, too, and has only one desire, to conquer the Yankees. I look for great things from him, and am glad to say that our troops have for him a great deal of the same feeling they had towards General Jackson. I am thankful to say he likes our old staff & has great confidence in me which I, of course, feel complimented at.”[i]

On June 3, the first Confederate movements of the Gettysburg Campaign started. During the next week, Ewell and his Second Corps, positioned as the lead elements of the Army of Northern Virginia, pushed steadily northward with the objective of entering the Shenandoah Valley and clearing a path for the rest of the army while the cavalry offered a protective screen for their march. They crossed into the Valley at Chester’s Gap, not far from Front Royal and headed for Winchester.

The men of the Confederate Second Corps had a particular connection to the Shenandoah Valley. Some called it home. Most called it familiar battleground by 1863. Many had fought in the region with Jackson or Ewell in 1862. The successes of the 1862 Valley Campaign still reigned in the soldiers’ and civilians’ minds as the example of Confederate leadership. The door was open for Ewell to be the next famed commander.

His chances improved significantly too, given the historic location of his first major battle as corps commander. Winchester. The prominent town in the lower part of the Shenandoah Valley had been the scene of one of Jackson’s most memorable victories. On May 25, 1862, Stonewall had sent Yankee General Nathaniel Banks reeling out of town and secured the admiration of the pro-Southern civilians in a sweeping military, morale, and civilian loyalty moment.

Ewell approached his personal crossroad with history as his army marched down toward Winchester. As the new commander of the Second Corps, he must have known his ability and reputation were under scrutiny. Fortunately for him, the imagery of a Confederate victory at Winchester – still fresh and exciting – could be repeated and possibly with even more glory. A hated Yankee waited in the famous town. If Ewell defeated him, his own legend could be firmly established – or so it seemed.

To be continued…

Source:

[i] Sandie Pendleton to his mother, June 9, 1863 – quoted in: Bean, W.G. Stonewall’s Man: Sandie Pendleton. (1959) University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill: NC. Page 133.

Enjoyable read !

I read Donald Pfanz’s biograpy of Ewell several years ago and came away liking him as a person, He definitely had personal courage pre-war but I thihk loosing part of his leg and his marriage changed him.

I agree. Ewell had been through a lot and his new relationship certainly affected some of his military focus – particularly in the autumn/winter of 1863. It’s my understanding that his leg did not heal properly due to a bad fall during his recovery. Definitely good points to keep in mind!

Pfanz’s book is solid. I’m not sure Gettysburg was a good test. Nobody – Lee, Hill, Longstreet, or Ewell – came out of that one looking good, and it’s very hard to say that Ewell did any worse than the others. I think the flaws became much more apparent over the winter of 1863-64 and were fully apparent by the Overland Campaign. Hill suffered the same course, starting with Bristoe Station and clearly aggravated by his medical issues.

I think there is something that underlies this discussion. Confederate leadership was, across the board, older than Union army leaders. Unlike Lincoln, as Mary Chestnut pointed out, Jefferson Davis did not weed out underperforming leaders. Perhaps the question we should be asking is why Lee chose a man who had been out of the war almost from the beginning & was suffering & compromised fby a medical condition as a corps commander?

After Stones River Rosecrans made the mistake of keeping Incompetent corps commanders in command. One of them was openly called a “chuckle head”. During the reorganization after Missionary Ridge, a lot of dross was removed from the officer corps. On the Sothern side, the same old cast of characters produced the same old poor results. Weeding the AoP would be a bloody business, but it was done.

Seems kind of contradictory that Jackson’s staff would accept Ewell because he was ‘like Jackson’. There are plenty of anecdotes where some among Jackson’s subordinates did not like him because of his peculiar ways, not least of which was not informing said subordinates of his plans and/or ideas.

Thank you for pointing this out, Douglas. I probably should have clarified better that I was highlighting staff officer opinions; the majority of those guys found ways to put up with Jackson’s quirks and became his biggest “fan club” after his death. I was looking at some archived letters recently from August 1863 and one of J’s staff officers was already in “defend his legacy” mode. Interesting! So far, I’m not finding that kind of legacy defense for Ewell.

Absolutely – Jackson was not beloved by all his subordinates. Ewell himself was not a Jackson fan for a long while in 1862! I think Ewell took what he didn’t like about Jackson’s leadership and tried not to repeat that when he got corps command, but that’s probably another set of articles. 🙂

In sharp contrast to the heavily-doctored spin concocted by many after Jackson’s death, we have the much more balanced (and critical) appraisal from E. Porter Alexander (especially in his personal memoirs which became “Fighting for the Confederacy). It would have been interesting to see how Stonewall would have fared in 1864-65 against the “A Team” – a question raised by Longstreet after the War.

Should have used my full name

This is no way personal. This article is emblematic of the habitual puffery that pervades Aop/AoNV writing. Ewell’s generalship was obviously not on a par with Jackson, Forrest, Claiborne & a constellation of Confederate officers of the first order. His “major victory” was a tactical victory that did not achieve a critical result. He drove Union forces back onto a hill that was the key to holding Meade’s right flank. That is not a victory, that is a major blunder. The Second Battle of Winchester was a tactical victory over one of the worst generals of the Civil War, which is really saying something. Puffing Winchester 2 up as a “major victory” puts it in the same class with the fall of Fort Donelson, for example.

Ewell was a good, run of the mill corps commander has to be great, legendary, an object of wonder… just because he served in the Army of Northern Virginia. Had Ewell performed at the same level in the Army of Tennessee, nobody would be declaring him another Claiborne.

How about we leave puffery to super hero movie advertisements & stick to objective history. That is, after all the whole point of what we do.

You make an interesting point:

” . The Second Battle of Winchester was a tactical victory over one of the worst generals of the Civil War, which is really saying something”

So what say you about the legendary Stonewall’s victories over the likes of Banks, Fremont and – drum roll, please – Milroy? Note that his big wins against this crowd featured his own tactical mediocrity compared to his opponents at Cedar Mountain, Port Republic/Cross Keys and – here we go again – McDowell. I’m leaving out his tactical screw ups at First Kernstown, the Seven Days, Brawner’s Farm, Day 2 of Second Bull Run, and Fredericksburg (remember the Gap). It seems that if any “puffery” is in play here, it isn’t this well done article. Instead it involves Jackson – one of those “Confederate officers of the first order”.

By the way, is “Claiborne” “Cleburne”?

Claiborne-Cleburne… an ongoing struggle with the spell check with my iPad. You make a good point about the deification of Stonewall. Unlike Hood & some other CW generals, Jackson did not live long enough for the war to transition from Napoleon-esque amateurisms mostly armed with smooth bores to a contest of veterans armed with rifled artillery & repeaters. In the Wilderness, Grant would have shrugged off a flank attack led by Jackson. A thrust at Washington led by Jackson would have been hounded to death by Sheridan; the days of Confederate corps running around the countryside unhindered were over. It is likely Jackson would have suffered a loss of prestige similar to his deciple Hood.

Those are good points. To be clear, I’ll give Jackson his due on the operational/maneuver level, if not always to the physical benefit of his command. But as a tactician he consistently earned a “C” grade. Even the great flank attack at Chancellorsville should have been more efficiently executed – hence Stonewall on a highly risky recon mission in the gloaming when he was mortally wounded. I have always thought that, as you indicate, Jackson’s historical reputation benefited from exiting the stage before Grant came east. Albert Sydney Johnston got a similar push by leaving us at Shiloh.

By the way, I find that posting from an iPhone is an almost insurmountable hurdle for accurate spelling. .

Fair point – Milroy was not a top-notch general, but I find it fascinating how Ewell pulls off a trap movement, forcing the surrender of several thousand troops. That’s what I wanted to focus on this time around. I’ll come back to Milroy at another time ’cause he’s quite a character!

Second Winchester was not a major victory in the grand scheme of history, but it was an important conflict at that time and context of the Gettysburg Campaign and key moment for Richard Ewell.

Don’t have to tell me about Milroy, I live in Murfreesboro TN. Not only did he fight a successful brutal anti guerilla war, he managed to out maneuver Forrest, of all people, & almost killed him at the Battle of the Cedars in November 1864. Like you say, Milroy was an interesting man.

Sarah: That will be interesting. To be fair to Milroy, I’m not certain that he was as incompetent as is suggested by the historical caricature which has persisted over the decades. He had Stonewall taking a deep breath at McDowell. But he also certainly wasn’t in anything close to the top tier. The same actually could be said of Banks – who had Jackson reeling for a time at Cedar Mountain despite being significantly outnumbered..