General Francis Barlow and The Letters He Destroyed on July 1, 1863

General Francis C. Barlow placed his division of the Union XI Corps on a rise of high ground, north of the town of Gettysburg. Without adequate reinforcements to anchor a defensive line, his exposed troops took the brunt of the leading units of the Confederate Second Corps rushing toward Gettysburg during the late afternoon of July 1, 1863. As his soldiers – mostly German-Americans – broke ranks and retreated in confusion, Barlow galloped in the chaos, trying to get ahead of his men and force them make a stand. He was probably angry; he hated stragglers, retreats, and had a heavy prejudice against the German immigrants who formed these units.

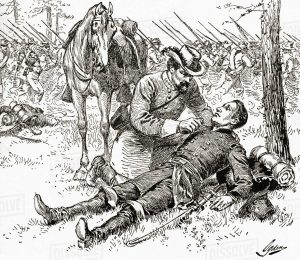

As he tried to rally the troops, a bullet struck him in the side and bored deep into his abdomen. He dismounted and attempted to walk off the field with the help of two soldiers. Feeling faint, he decided to lie down and await his fate: likely death or capture. His soldiers ran or hobbled by. The enemy bullets ploughed into the ground around him, one striking his hand, another cutting through his hat. In severe pain and with blood soaking his clothing, he still had the presence of mind to think about what lay hidden in his pockets.

“As I lay in the field before the enemy reached me I remembered that I had two of those letters in my pocket + that the enemy might not be inclined to parole so important a functionary as the “Superintendent of the Freed Men throughout the U.S.” So I destroyed the letters together with all others in my pocket.”[i]

Barlow destroyed valuable primary sources, but given the circumstances, his decision is understandable. In his July 7th letter, he did not elaborate about the letters because his mother had been aware of the entire saga. Years, later the history in those letters can be pieced together, and it reveals a fascinatingly side of this New Englander with a set of complex character qualities.

At least as early as April 28, 1863, Barlow wrote to his mother, explaining: “I have written to Lowell that I am still ready to take command of the Negro brigade if it is desired.”[ii] The Emancipation Proclamation had opened the door for African Americans to official serve in Federal military forces – army and navy. Massachusetts formed the first regiments of U.S.C.T. and hundreds of from black communities across the north rushed to serve. Barlow had a successful war record by the spring of 1863, rising from private to brigadier general on leadership merit and through the influence of his wife and friends. He also had plenty of connections in the Boston area since he had spent most of his youth in Massachusetts.

Colonel Robert G. Shaw, whom Barlow had tutored in preparation for Harvard, anticipated his older friend taking command. His letters reveal the influence of the abolitionists and power holders in Massachusetts. On March 17, 1863, Shaw wrote to his mother about recruiting the 54th Massachusetts and the possibility of forming a brigade of U.S.C.T. “The regiment continues to flourish. Men come in every day. Mr. Stearns, who is at home for a few days from Canada, says we can get more men than we want from there. The Governor thinks of getting authority to raise some more coloured regiments. If he does, I hope Frank Barlow can get the command. He is just the man for it, and I should like to be under him.”[iii]

Shaw continued advocating and wishing for his friend in the next months. From St. Simon’s Island on June 18, he corresponded with family, saying: “Frank Barlow still wishes to get command of a coloured Brigade, and I think it would be a great piece of good fortune for us if we could get him – & for the cause, as well. If Father can do anything towards it, I wish he would.”[iv] Two days later, he continued pressuring the family to use their influence: “Now you are so near Headquarters, can’t you do something towards getting Barlow for us? I have just heard from him under date of May 21. He says he had just received yours of March 20 & regrets very much not having got it before. He still wishes to command a colored Brigade & I have no doubt we should do something under him.”[v]

While Robert Shaw focused on a brigade command for his former tutor, Barlow himself had set his sights higher. A June 2 letter to his mother revealed correspondence with a powerful abolitionist. “I have just recd the enclosed letter from Dr Howe which is confidential + is to be kept secret. I have telegraphed him to write particulars. Politically it would be a great advantage to me, but I doubt my ability to fill the place + I dislike the idea of leaving the active service for which I am well fitted. I will write you more about this when I hear from Dr. Howe. Edward would like me to take the place I think…”[vi]

Barlow referred to the position of superintendent general of an emerging program for freedmen. In March 1863, Secretary of War Stanton had appointed Robert Dale Owen, James McKaye, and Dr. Samuel G. Howe to investigate how the Federal government could help newly freed slaves adjust, settle, and build successful, self-sufficient lives. Their first recommendations focused on giving employment with Federal forces already located in the South and to divide the program supervision into three departments, consisting of approximately 5,000 freedmen in each. The program they envisioned needed a military officer with the rank of brigadier general to oversee the efforts and ensure that the military behaved with proper respect toward these freedmen seeking employment in the camps or to build fortifications. It would have been a prestigious position for social work and doubtless offered the opportunity for political recognition too.

On June 26, as the Gettysburg Campaign unfolded slowly for the Army of the Potomac, Barlow wrote to his brother Richard. “There seems to be quite a force of them [Rebels] in Maryland + I hope we shall have a battle which will settle the matter one way or the other. You know I presume that when this immediate Campaign is over I am going to accept the “Darkey Superintendent” place if it is then open to me. I am expecting to have a letter from Robt Dale Owen on the subject every day…” At the end of this letter, he emphasized, “Don’t speak of my darkey plan.”[vii]

Barlow’s language is startling to modern readers, spotlighting one of the problems in the abolitionist community of that era. Francis Barlow supported abolition and interacted with some of the power figures of that movement – but like other contemporaries – he did not equate freedom with equal rights. Many in the abolitionist movement opposed slavery and truly wanted to help the freedmen, but still did not see “all men created equal.” Barlow seems to fit into this category of “limited social reformer.”

Researcher Christian G. Samito who annotated and published a collection of Barlow’s letters raised the question, “What would Barlow have done if he got the superintendent position?” So far, no letters have surfaced with his plan for program administration, goals, or steps to help the freedmen. He did not elaborate ideas to his family in surviving letters. While this does call into question his motives, perhaps it is unfair to judge that he only wanted the position for political motives since detailed outlines could easily have been lost, destroyed, or simple never committed to paper.

The significant part of Barlow’s interest in this position of Superintendent of Freedmen or brigade commander for U.S.C.T. comes in the comparison to his fellow officers. Unless they had an abolitionist background, most Union officers did not want to command black troops, especially in the early months of their recruitment. The ideal of training and leading black soldiers never seemed to be a problem for Barlow. If it had been an issue, he likely would have written about it since he did not hold back on other prejudices. In a complex situation, Barlow spent his war years hating German-American soldiers, but never really saying much about Irish-American recruits – creating a situation of nonconformity to the traditional nativist view of that era. Also, he had no problems with the ideas of interacting with African Americans and linking his name (and political fortune) to their cause.

The significant part of Barlow’s interest in this position of Superintendent of Freedmen or brigade commander for U.S.C.T. comes in the comparison to his fellow officers. Unless they had an abolitionist background, most Union officers did not want to command black troops, especially in the early months of their recruitment. The ideal of training and leading black soldiers never seemed to be a problem for Barlow. If it had been an issue, he likely would have written about it since he did not hold back on other prejudices. In a complex situation, Barlow spent his war years hating German-American soldiers, but never really saying much about Irish-American recruits – creating a situation of nonconformity to the traditional nativist view of that era. Also, he had no problems with the ideas of interacting with African Americans and linking his name (and political fortune) to their cause.

However, his goals and ambitious to help the freedmen or command black troops were dangerous on the battlefield. The hoped-for letter from Mr. Owens announcing Barlow’s nomination as the “Negro Superintendent” arrived sometime between June 26 and July 1 as the XI Corps plodded northward. [viii] Realizing he was about to be captured as he lay wounded on the battlefield that July 1 afternoon, Barlow carefully destroyed all the letters in his pockets. He did not elaborate on the destruction method; perhaps he tore them up, scattering the pieces in the grass, perhaps he doused them with liquid from a canteen or flask. Somehow, he got rid of the evidence that could have made him a dangerous man to the Confederate social system.

As an aside, Barlow’s claim that he destroyed all the letters lends interesting light to the controversial story about Confederate General Gordon. Stories vary between Gordon sitting and reading letters to the wounded Yankee or simply destroying a packet of letters that the Union officer claimed were from his wife. It is possible that Barlow could have asked Gordon to destroy the letters, but the wording in his own July 7th letter about the incident indicates a panic to get rid of the letters before the Confederates arrived, making it suspect that he would have handed over those exact letters to an enemy general. Barlow certainly interacted with Confederate officers from the Second Corps and could easily have encountered General Gordon, but his claim that all letters had been destroyed before Confederate interactions begin certainly casts doubt on pieces of the post-war story.

Wounded and “in considerable pain” with blood saturating his “trousers + vest + both shirts”, Barlow was carried to the Josiah Benner farmhouse. That evening Confederate surgeons chloroformed him, probed the wound, and when he awoke, informed him that the wound was mortal. Aware of the dangers of his abdominal wound, he still refused to give up and spent the next battle days “very comfortably under the influence of morphine.” Luckily for him, the Confederate doctors still believed his wound was mortal and left him behind when they retreated. With the Union back in control of Gettysburg, Barlow’s wife arrived and took over his care, using her nursing skills acquired with the U.S. Sanitary Commission to save his life for the second time.

During the summer while Barlow fought against pain and gradually knew he would survive, his friends still pressured for his appointment to command U.S.C.T. Colonel Robert G. Shaw wrote to his sister on July 13, 1863, “Governor Andrew writes that he has urged the Secretary of War to send General Barlow here to take command of the black troops. This is what I have been asking him to do for some time.”[ix]

However, Barlow’s wound and initial quick healing took a turn for the worse. By late summer and through the autumn months, he complained of severe and frightening nerve pain running through his abdomen, hips, and thighs. The pain prevented him from sitting or standing, and he spent long, agonizing weeks on a stretcher, moving from place to place in the north and visiting different doctors in search of relief. Clearly unable to take the field for active command, his friends had to quietly end their advocacy. When Barlow did return to field duty in 1864, he accepted a division command under General Winfield S. Hancock in the Army of the Potomac’s II Corps.

The history of the destroyed letters reveals more of Barlow’s complex character. Though heavily prejudiced against his German-American troops at Gettysburg, his abolitionist beliefs inspired him to seek a leadership position with black soldiers or to aid freedmen build successful lives. His word choice is sometimes jarring to modern readers, but as we try to understand the context and his era, it is clear that Barlow took a position and interest in abolition, slavery, and freedmen far different from other Union officers. His willingness to take the positions and – presumably pursue positive measures – marked him as a social and political enemy to the Confederacy.

Lying on Gettysburg battlefield with a bullet in his gut, Barlow realized the impact of the correspondence in his pocket. His decisions and the written words he carried would mark him as a committed abolitionist and a warrior for freedom – something his Southern captors probably would not appreciate. Barlow destroyed the important letters, an unfortunate occurrence for researchers. But the history surrounding those particular letters survived, giving another piece of General Barlow’s story and another facet of his fiery, sarcastic, determined, and dedicated personality.

Sources:

Welch, Richard F. The Boy General: The Life and Careers of Francis Channing Barlow. (Kent, Kent State University Press, 2003).

Coco, G.A. A Vast Sea of Misery: A History and Guide to the Union and Confederate Field Hospitals at Gettysburg, July1-November 20, 1863. (Gettysburg, Thomas Publications, 1988).

Hartwig, Scott. “Romances of Gettysburg – The Barlow-Gordon Incident.” https://npsgnmp.wordpress.com/2012/03/15/romances-of-gettysburg-the-barlow-gordon-incident/

[i] Barlow, Francis C. edited by Christian G. Samito. “Fear Was Not In Him”: The Civil War Letters of Major General Francis C. Barlow, U.S.A. (New York, Fordham University Press, 2004). Page 166.

[ii] Ibid., Page 127.

[iii] Shaw, Robert. G., edited by Russell Duncan. Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Robert Gould Shaw. (Athens, The University of Georgia Press, 1992). Page 309.

[iv] Ibid., Page 354.

[v] Ibid., Page 355.

[vi] Barlow, Francis C. edited by Christian G. Samito. “Fear Was Not In Him”: The Civil War Letters of Major General Francis C. Barlow, U.S.A. (New York, Fordham University Press, 2004). Page 136.

[vii] Ibid., Pages 143-144.

[viii] Ibid., Page 166.

[ix] Shaw, Robert. G., edited by Russell Duncan. Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Robert Gould Shaw. (Athens, The University of Georgia Press, 1992). Page 381.

I think we have to be careful about projecting modern sensibilities onto 19th Century figures. The negative shadow that the use of “darkey” or even other, stronger, slang for blacks, would cast over someone today, did not exist back then. It was just common slang, widely used by many, and IMO very little should be read into it.

I agree that the language was common in that era, but it can still be startling to modern readers who are not familiar with the “slang” uses – hence, the limited note on it. It remains that Barlow was willing to lead USCT or oversee a freedmans’ agency in an era when many others would have turned down that opportunity due to racial prejudice.

Modern readers should be used to ” upsetting language” if they are aware of modern films, books,and music. But you know that.

Barlow was an extraordinarily ethical lawyer who helped clean up the corrupt New York judiciary after the war. When assigned to review the vote totals in Florida after the hotly contested 1876 presidential election, his integrity was such that he angered his fellow Republicans by determining that the Democrat had won Florida.

Barlow was surely an interesting figure. One of the few clean shaven men during that time period. You would not think him rough enough to use the flat of his sword against a man’s back without a fight. Could the Harvard boy fight? After being nursed back to health by his wife, she died soon thereafter and he immediately remarried. One of the many graves I would like to visit, I hear he is buried in Brookline Mass.

Barlow was seriously wounded at Antietam as well.

His first wife Arabella Griffith Barlow–who was 10 years older than him–died in July 1864 (age 40) from typhoid fever, which she acquired while working in various army hospitals during the Overland Campaign. Barlow’s was crushed by her sudden death and suffered a physical and probable emotional breakdown by August 1864 and took a leave of absence from the army. He returned to the army during the final week of the war in April 1865 and was given the 2nd Division, 2nd Corps, when its commander (William Hays), was fired for over-sleeping during the march.

Barlow remarried in October 1867 to Ellen “Nellie” Shaw, the sister of Robert G. Shaw and they went on to have three children. General Barlow is buried in Walnut Street Cemetery in Brookline, along with his mother and brothers. For many years after his death, his tomb was unmarked until a bronze plaque was added. Ellen Shaw died some 40 years later in 1936 and is buried in the Shaw family plot in Staten Island.