Ending the War, More or Less

April 9, 1865, is the day that most people think the American Civil War came to an end. General Robert E. Lee realized his gallant Army of Northern Virginia was simply too beaten up to continue its fight for Confederate independence. Union General Ulysses S. Grant stopped his headachy ride about noon when he saw the Confederate courier coming his way. Might this be it? Finally? It was. Lee requested a meeting, and Grant’s headache disappeared.

April 9, 1865, is the day that most people think the American Civil War came to an end. General Robert E. Lee realized his gallant Army of Northern Virginia was simply too beaten up to continue its fight for Confederate independence. Union General Ulysses S. Grant stopped his headachy ride about noon when he saw the Confederate courier coming his way. Might this be it? Finally? It was. Lee requested a meeting, and Grant’s headache disappeared.

The surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia is legendary. It was held at the McClean House, owned by the same Wilmer McClean who had decided, after First Bull Run exploded in his front yard, to move to a quieter place. Lee wore a spotless officer’s uniform; Grant’s attire was mud-spattered and informal. Lee got to the house first and waited for about thirty minutes. Grant claimed later that all the chit-chat in which he and General Lee engaged when he finally arrived was because he was embarrassed to ask Lee for his surrender. The generals agreed upon terms: Lee’s men got to keep their horses, and Grant sent over 25,000 rations to ease the southerners’ hunger, if not their pride.

The surrender at Appomattox became a subject for paintings, poems, and legends. Soldiers on both sides chopped an apple tree on McClean land into matchstick-sized pieces as souvenirs. At last, the war was over . . . except it wasn’t. Lee only surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia. There were six more surrenders to go.

Confederate General Joseph Johnston made the second most famous surrender to Union General William Sherman. In early April, Sherman pursued Johnston through North Carolina, but when the news of Lee’s surrender to Grant reached Johnston, he sent an immediate message to his foe. He asked for a meeting, and Sherman obliged him. Both men met at Bennett’s Place in Raleigh, North Carolina. On April 18, Sherman offered Johnston the same terms offered to Lee. Additionally, he offered to restore United States citizenship to all surrendering Confederates. The powers in Washington were not pleased. Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated on April 14, and Andrew Johnson was now President. It took the personal intervention of General Grant, armed with a letter from Lincoln regarding the surrender of Confederate forces, to sort out the treaty terms. Johnston’s second attempt to surrender his army to Sherman was completed on April 26, 1865.

One would think that two surrenders would be enough to end the war. Not so. The Confederate forces were widely scattered and not uniformly organized. Union general Henry Halleck advised the federal army that those who chose not to surrender be treated as prisoners of war. Except for Colonel John Mosby: “the guerrilla chief Mosby will not be paroled.” Miffed, Mosby offered an armistice. Wires flew back and forth. Mosby kept asking for more and more time. On April 20, General Winfield Scott Hancock told Mosby the time had run out. Rather than surrender, Mosby disbanded his unit on April 21: “I disband your organization in preference to surrendering it to our enemies. I am no longer your commander.” Two months later, Grant interceded, accepting Mosby’s parole. “The Gray Ghost” went back to being a lawyer.

Although Lee and Johnston had signed surrenders, there were still armed Confederate troops in the West, the Trans-Mississippi, and Indian Territory. Confederate Lieutenant General Richard Taylor commanded almost 10,000 men in Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana. After hearing of Lee and Johnston’s actions, Taylor agreed to meet with Union major general Edward Canby a few miles north of Mobile, Alabama, on May 2. They agreed to a 48-hour truce. On May 4, 1865, General Taylor surrendered his command to Canby under the same terms agreed upon by Lee and Johnston. Nathan Bedford Forrest, whose authority fell under the geographic jurisdiction of Gen. Taylor, surrendered his Confederate cavalry corps a few days later. On May 9, at Gainesville, Alabama, Forrest advised his men to, “Obey the laws, preserve your honor, and the Government to which you have surrendered can afford to be, and will be, magnanimous.”

Confederate lieutenant general Kirby Smith commanded the Trans-Mississippi Department. He did not sign a surrender until May 26, 1865. Smith was angry. Rather than be prosecuted for treason, the former West Point graduate escaped to Mexico and then Cuba. After President Johnson’s proclamation on May 29 concerning amnesty and pardons, Smith returned to Virginia and took the amnesty oath later that year.

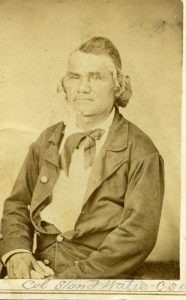

Members of the Cherokee Nation fought on both sides of the war. The most famous Native supporter of the South was Stand Watie. Watie became colonel of the First Cherokee Mounted Rifles, was promoted to brigadier general in early 1864 and commanded the First Indian Brigade. The sovereign Indian Nations were not included in the surrender of the Trans-Mississippi Department. It took the convention of a native-controlled Grand Council to decide the particulars, and on June 23, 1865, Cherokee, Creek, Seminole, and Osage fighters surrendered near Fort Towson, in Indian Territory. Brigadier General Stand Watie was the last Confederate general to surrender his command.

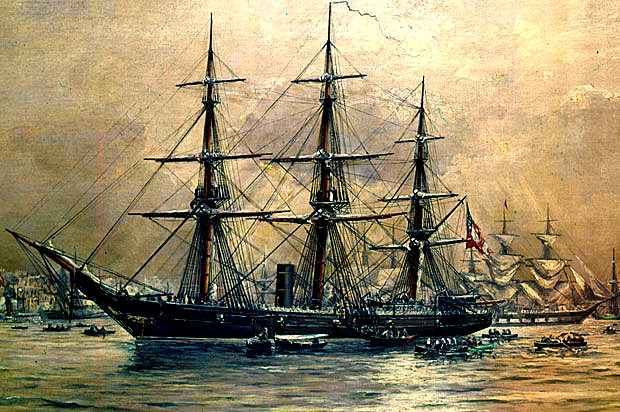

The final surrender took place in Liverpool, England. The Confederacy bought the British-built trading ship Sea King in the fall of 1864. Captain James Wadell switched the English crew with a Confederate crew, transformed the vessel into an armed raider, and named her the CSS Shenandoah. The ship took a round-about way that included going around the Cape of Good Hope to reach the Pacific, where its mission was to attack Yankee whalers operating in the Bering Sea. The Shenandoah was in Micronesia when Lee surrendered at Appomattox, and Captain Wadell and his crew were unaware that the war had ended. They continued their destruction of Yankee vessels and by August 1865, the Confederate raider had captured or destroyed thirty-eight ships, including whalers and merchant vessels.

A British ship told Wadell that the war was over, and sadly the captain and his crew turned the CSS Shenandoah around and headed toward England. On November 6, 1865, the last Confederate surrender occurred when the raider reached Liverpool. Wadell surrendered by letter to Lord John Russell, the British prime minister. The CSS Shenandoah became the El Majidi, sailing under the control of the sultan of Zanzibar.

On April 2, 1866, President Andrew Johnson formally declared that the war had ended–except in Texas. That took another seven months. On August 20, 1866, Johnson again issued a formal proclamation announcing the war’s end: “…peace, order, tranquility, and civil authority now exists in and throughout the whole of the United States of America.”

Seven surrenders. Well, it was a long war. Hundreds of thousands gave their lives and fortunes to see it through. It took the Confederacy a year and a half to completely concede. Seven, and still, the fundamental causes of the war are with us today. Lincoln’s words–“With malice toward none, with charity for all”–have not yet come to pass. Those of us who write about this war have unique perspectives. The Civil War defines our world view. Personally, I won’t be surrendering that view any time soon myself. I suspect neither will you.

Still…seven surrenders.

Great post, Meg. But it could be argued that Shenandoah never surrendered. Captain and crew just abandoned the vessel to a neutral power and disbursed. The victors never got their hands on these former Rebels, who eventually returned home and resumed their lives.

Very good Meg.

McLean house of Wilmer not Alexander McLean

Where were all 7 surrenders? Besides Appomattox ?