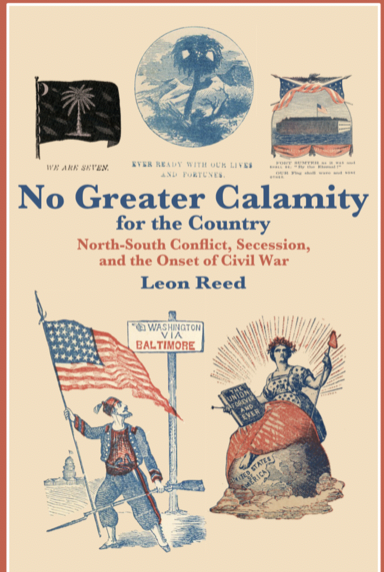

BookChat with Leon Reed, author of No Greater Calamity for the Country

I was pleased to spend some time recently with No Greater Calamity for the Country: North-South Conflict, Secession, and the Onset of Civil War, a new release by Leon Reed from Little Falls Books. Leon was kind enough to take a few minutes to chat with me about his book.

I was pleased to spend some time recently with No Greater Calamity for the Country: North-South Conflict, Secession, and the Onset of Civil War, a new release by Leon Reed from Little Falls Books. Leon was kind enough to take a few minutes to chat with me about his book.

Do you think the onset of the war gets enough serious attention?

There have been two popular books, David Detzer’s Allegiance: Fort Sumter, Charleston, and the Beginning of the Civil War (Harcourt, 2001) and Adam Goodheart’s 1861: The Civil War Awakening (Knopf, 2011), and a number of books written for a popular audience but published by academic presses, notably Elizabeth Varon’s Disunion: The Coming of the Civil War and John Lockwood’s The Siege of Washington.

But considering the importance of the events secession led to and its relevance to the present day, no, I think it’s one of the most under-studied topics of the Civil War. Consider that there are probably more books about a one-hour fight for Little Round Top than the entire secession crisis and this inattention becomes obvious. I’d like to see more work on the border states, on the fire eaters, on the transformation of public opinion, on the Buchanan lame duck period, on the details of forming the Confederate States of America, and on the military mobilization for the war.

How does your book bring new light to the discussion about the lead-up to the war?

First, I think the attention to the historic value of patriotic covers is an important insight. In addition, while I’m not the first one to make the point, the last-minute changes of view by so many people on both sides is an important point. I don’t subscribe to the view that the war might have been avoided, but the decisions that led to secession and civil war at that time and place were in many cases made at the very last minute.

Finally, the state-by-state focus on the border state secession decisions highlights a crucial set of policy decisions that had a huge influence on the war. The four states that seceded last (NC, AR, VA, TN) doubled the white population of the CSA and added immeasurably to its industrial strength. The three states that didn’t secede (MO, KY, and MD—I don’t count DE because it was never in play) would have added a similar increment of population and industry—and shifted the border even further north.

You mention that the effects of the war are “still some of the strongest economic and political influences in 21st century life.” What would you say is the #1 economic and the #1 political influence we’re still feeling?

Economically, the war largely marked the fulfillment of Hamilton’s dream of a strong national government and a nationalized economy with top-down instruments to promote financial stability. It also did much to create the modern corporation and its dominance over our economic and political life.

Politically, we have two dominant issues: the eternal debate between state’s rights and federal power and the longstanding and seemingly insoluble race crisis.

Do you think modern Americans are aware that those effects are things that can be traced back to the Civil War? Why/why not?

I doubt many think much about the extent to which the Civil War created our modern economy. Politically, there is more understanding of the link between the Civil War and current political issues, though the continuing debate about whether slavery was central in secession and the onset of the war illustrates that many people misunderstand this linkage. Even the understanding of this topic is a matter of current political controversy, which further shows the extent to which the war affects our politics.

This project is, in a way, grounded in a scrapbook passed along to you by a relative. Can you tell us a little bit about that scrapbook?

I remember at the end of my high school graduation ceremony, I shook hands with my cousin Jim and we said good luck—and for the next 48 years we had almost no contact. Like so many others, we got back in touch via Facebook and the relationship matured to the point we started having monthly phone calls—which now last 2+ hours. In one of our early calls, Jim said ‘You’re so interested in the Civil War, would you be interested in a scrapbook my ancestor put together during the war?’

The scrapbook is the most fascinating thing I’ve ever seen. Jim’s 2-great grandfather, Hiram Roosa, was corresponding secretary of the New York Military Association and an avid collector. His scrapbook is a treasure. It contains original correspondence (including a letter written by Major Robert Anderson from inside Ft. Sumter during the siege), souvenirs (Confederate currency, scraps of flags, etc.) sent to him by New York soldiers in the field, narrative write-ups of significant events (Ft. Sumter, Ellsworth and the occupation of northern Virginia, etc.), photographs (including, I’m told, a rare photo of John Brown), and, most important, a collection of about 300 patriotic envelopes that were printed on both sides during the first few years of the Civil War (these envelopes were also called “covers”).

The scrapbook also contains some real oddities: the 1832 bylaws of the “Rondout Guards,” forerunner, I assume, of the Ulster Guard and a “Presidential Offer of Pardon and Amnesty,” written in the Cherokee language, for example.

The book is organized chronologically but it’s also grounded in the scrapbook, which makes for a really interesting organizing conceit. Were there challenges to that?

The book evolved as my understanding of the collection improved. “What’s all this punning in the envelope about Lion and something that happened at Boonville?” Oh, an important skirmish that helped ensure Missouri would remain in the Union? Good story, let’s write that up. Working with the scrapbook was a real detective story—or maybe a scavenger hunt. Sometimes a simple Google search was enough to identify a topic I didn’t immediately recognize in a particular cover, but sometimes it took quite a bit of digging. Lincoln Comet? Artemus Ward? What the heck was Mill Spring? Captain Thomas and the French Bureau? Repudiation? Wide Awakes? Young America? Each of these, after a bit or quite a lot of digging, turned out to be an interesting story.

What is the best story you retell in the book?

There are so many it’s hard to pick. My favorite individual story was about Ben Butler and “Contraband.” The overall subject of “contraband” was a very popular topic with the printers who made patriotic envelopes. Clearly it captured the imagination of people in the north. Three slaves escaped to Fort Monroe and Butler, a clever trial lawyer, finessed the standing orders not to “interfere with local institutions.” Avoiding the decision whether to declare them free or send them back, he simply confiscated them as “contraband of war,” much as he would seize a cannon. When a representative of the owner came and requested their return under the terms of the Fugitive Slave Act, Butler reacted in mock surprise, why, sir, you claim to be a separate country; how can I possibly have any obligations to you under federal law? When the Lincoln administration approved Butler’s action, a major step toward emancipation had been taken: the word passed almost instantly through the slave communities and federal posts everywhere saw a trickle of escaped slaves grow to a flood.

You actually take the book well into 1862, even though it’s ostensibly a book about secession and the onset of war. Can you talk a little bit about how those post-secession events shed some light on secession itself?

The book really emerged from the scrapbook: if I had a cover that I understood and that made an interesting point, I included it in the outline. Eventually, a topical organization emerged. Ooh, we have enough about privateers and other naval events to have a separate chapter, for example. The collection tailed off in mid 1862, so that was a logical place to end the book. But I think it’s a logical stopping place. The battle at Manassas was a major turning point, but the way ahead was still unclear. By mid-1862, everyone knew this was a long-term effort. Enough had fallen to suggest the ultimate carnage. The people who were going to settle things (Lee, Grant, Sherman, etc.) had begun to emerge as strong leaders and fighters. Both sides were raising mass armies for a long war. We could see the diplomatic and financial issues. And, significantly, the first signs of war weariness were beginning to emerge.

What significance do you think the scrapbook has for historians?

I think the patriotic covers are under-appreciated historic documents. They illustrate the significant events, heroes, and martyrs and some more obscure ones. They provide insights into public opinion—if there are a lot of covers on a specific topic we can assume that topic sparked interest among the public. For example, on the contraband story I mentioned above, there are at least a dozen covers with this theme. This indicates that there was a significant degree of interest among the northern public in this topic. Although abolition didn’t become policy for another year and a half, this indicates that the escape of slaves was of interest within the Northern public.

Aside from the scrapbook itself, what was your favorite source you worked with while writing the book?

I was talking with Gettysburg park ranger Matt Atkinson about the project and he asked if I was familiar with Frank Moore’s Rebellion Record. I’m chagrined to say I wasn’t, but it became an essential source.

My most serendipitous source came while on vacation in New Mexico last fall, when the book was all but finished. The day we went to Ghost Ranch (Georgia O’Keeffe’s hangout), we stopped at an antique store in a nearby village. There on the wall, I found an 1861 military map of the United States, a national map with many insets. After a nice discussion with the owner (He asked me, among other things, whether I thought Lincoln was the greatest president or the worst, another example of the war’s continuing influence on our political discourse), he gave me a good price. I used copy photos of that map extensively in the book.

Who, among the book’s cast of characters, did you come to appreciate better?

I found John Dix to be one of the most fascinating characters of the war. He was everywhere and seemed to be one of Lincoln’s favorite problem solvers: organizing New York’s mobilization, receiving Treasury funds directly to help form regiments and buy transport, arresting the Maryland legislature, negotiating the first prisoner exchange agreement, sorting the New York Draft Riots.

What’s a favorite sentence or passage you wrote?

Like all good journalism students from way back, I learned that you lead with the most important sentence and build from there. My favorite sentence, the first sentence written by me in the book, is a mouthful:

These comments, one written by a southerner who loved the Union but would soon be making war against the Union; a second written by a Northerner who respected and admired the South but would soon be making destructive war against the South; the third written by an ardent Unionist from Georgia who within a few months was vice president of the new Confederate States of America; and a fourth written by a pro-Southern New York politician and businessman who within six months was the most senior major general of Union volunteers and was supervising the arrest of potential secessionists in Maryland, perfectly illustrate the contradictions and dilemmas involved with the secession crisis and the onset of Civil War.

As a former English as a Second Language teacher who had “short sentences with simple grammar” drilled into him, I look at that sentence with wonder, but it makes an important point. A few fire eaters and a very few abolitionists knew the path they were on for a decade, but for many, the decision to support secession or to resist it with military force was a last minute decision arrived at after prolonged thought.

What modern location do you like to visit that is associated with events in the book?

I think Fort Monroe is one of the underappreciated historic locations in the country. There is so much American history within a few miles of that site. The places I need to get to include Charleston and St. Louis, especially the arsenal.

Is there any topic that sparked your interest for further research?

I came away fascinated with the operations of the organization Roosa worked for, the New York State Militia, in the early days of the war and in particular, the hometown regiment from Roosa’s town, the Ulster Guard (20th New York State Militia). I did an hourlong power point on this topic and posted the presentation on my facebook page.

What’s a question people haven’t asked you about this project that you wish they would?

“Can I buy a copy of your book?”

More seriously, one I’d always be interested in discussing is “Do you see parallels between the north-south crisis and our present situation?”

————

Leon Reed is a former congressional aide (US Senate Banking Committee), defense consultant, and US history teacher. He now lives in Gettysburg, where he photographs the park, volunteers helping people research their civil war ancestors in the visitor center (when it’s open), heads up the county’s 2020 Census Complete Count Committee, and writes military history. He is the co-author, with his wife Lois Lembo, of the forthcoming Savas Beatie title, “A Combat Engineer With Patton’s Army: The Fight Across Europe With the 80th “Blue Ridge” Division in World War II.”

Good interview. It makes sense that the battles and leaders get most of the coverage while the origin of the war get less. Everyone loves a good war story. However, the origin is more complicated and often dry reading. I thought the Varon book was excellent.

Leon

What did you find the most perplexing oxymoron that influenced the beginning of the war most?

timm

slimtimm, not sure an oxymoron, but the most astounding/puzzling thing was the speed with which opinions changed. Even in the deep south, I doubt anything like a majority contemplated secession, even as late as late summer 1860. The difference between fire-eaters like Yancey and Wigfall and middle of the roaders like Jefferson Davis and Unionists like Toombs and Stephens were largely disageements about political tactics, not goals. The rate at which southern Unionists (in January and February) and then upper south Unionists (in April and May) abandoned long-held positions and came around to secession was remarkable. Equally, southern sympatizers in the north, like John Dix and Dan Sickles and Ben Butler abandoned their support when the southern states seceded and then fired on Fort Sumter. I suspect if you had done a poll, say, a year before First Manassas, and asked “what do you think the chances are that we’ll be at war against each other a year from now?”, you’d have had less than 1/4 answer yes.

Thank you Leon for sharing your Civil War knowledge, and focusing on the details of the recipe for the war as well as contrasting social opinions.