Manticores, Myths, and Memory (conclusion)

(Part four of four)

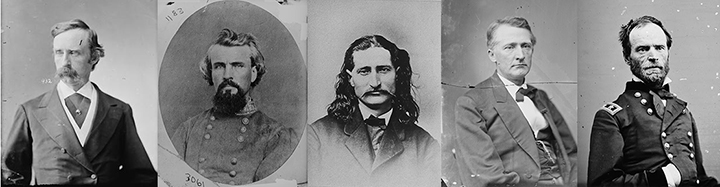

Paul Ashdown and Ed Caudill are co-authors of the latest book in the Engaging the Civil War Series, Imagining Wild Bill: James Butler Hickok in War, Media, and Memory (Southern Illinois University Press). Their work on Hickok parallels other work they’ve done on Custer, Forrest, Mosby, and Sherman. The memories of all five men have followed a familiar process of national myth-making.

Conclusion: The Epicenter of Imagination

The facts of history are indifferent to their audience, but myths make history useful by giving storytellers, journalists and historians a context for validation by their audiences. Thus, historical memory, undergirded by select and relevant facts, often is used to support ideology rather than gain a deeper understanding of the past. The recent frenzy by some to ordain the United States a Christian nation illustrates one way in which historical narrative, with select facts, is put to the service of ideology. In spite of a well-documented history of the Founding Fathers’ antipathy to a state religion, the First Amendment’s establishment clause, and the 1797 Treaty of Tripoli, many people in the 21st century insist the United States was created as a Christian nation.[1]

This is what Michael Kreyling deems “counterfactual history,” which, however repulsive to the purist, may serve immediate political and social needs. Kreyling cites Civil War novels in which the war ends in a negotiated truce, and in which Robert E. Lee, like Abraham Lincoln, is a pragmatic emancipationist seeking gradually to end slavery. Such counterfactual history absolves the South by recasting Lee as ultimately fighting for a morally defensible cause—just like Lincoln. Therefore, modern Southern pride is not necessarily racist: “In other words, alternate history attempts to alter what we remember about the past to create a plausible (simulated) ground for a counterfactual present in which certain political positions can be held without the burden of knowing that they have already failed.” Similarly, the Christian nation ideologues find validation in a contrived narrative including iconic, even mythic, figures in the founding of the nation.[2]

Likewise, myth permeates post-Civil War history, which teems with fantastic characters, blown to the surface by the depth charge of war, many of whom were resurrected, like Custer, Hickok and Jesse James, in the Wild West. Their exploits and outrages spawned fictional and semi-fictional characters who captured the imaginations of succeeding generations. The Western stories that filled newspapers, magazines and dime novels came to life in tent shows and on stage, screen and television, from Dodge City to Deadwood. They all shaped public history.

Peering into myth and memory casts new light on how the Civil War and its immediate aftermath remain at the epicenter of our collective imagination. Historical manticores abound, for, as the philosopher David Hume observed in a different context, “To form monsters, and join incongruous shapes and appearances, costs the imagination no more trouble than to conceive the most natural and familiar objects.”[3]

————

[1] David Rieff, In Praise of Forgetting: Historical Memory and Its Ironies (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016), 22. On the issue of the Founding Fathers and the idea of a Christian nation, see Brooke Allen, Moral Minority: Our Skeptical Founding Fathers (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006), and Forrest Church, So Help Me God: The Founding Fathers and the First Great Battle Over Church and State (New York: Harcourt, 2007).

[2] Michael Kreyling, A Late Encounter with the Civil War (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013), 76-77, 84.

[3] David Hume, An Inquiry Concerning Human Understanding, in The Philosophical Works of David Hume, Vol. 2 (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1875), 14. Originally published in 1748.

A general thought:

I think everyone knows that the Puritans were Christians and they came to America to live their Christianity to the fullest. It is very easy to mythologize from that beginning and more so because Protestantism came to blossom fully in America. The first amendment itself wonderfully allows for and shields such Christian belief and mythology.

People are ever creating such mythologies from history, today we can observe literary and progressive America’s lauding of the 1619 Project. If there ever is a history project in our time that exists to feed immediate political and social needs, this is it. Jubal Early no doubt respects where these folks are coming from.

If anything it seems to me there is a great reticence in considering the role of religion at all in America’s founding myths. Sure, we all learn about the Pilgrims and that they wanted some sort of religious freedom, but that’s about it except maybe a little about Quakers in Pennsylvania.. If anything, religion was a dominant question of 17th c England, and affected all areas of life. It’s hard to accept that this had little influence in the American colonies. Then the 18th c in some sense sorted things out (except maybe for Catholics in both England and the colonies). So what about the influence of the Great Awakening and subsequent rise of Methodism and the Baptists in the colonies? It seems this inattention would have to be considered if we try to establish that there has been myth creation regarding a “Christian nation”.

I think we tend to place our own meaning of the word Christian according to our particular theology

timm

Christian myth?

George Washington, a Christian, said in his farewell address– “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of patriotism, who should labor to subvert these great pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of men and citizens. The mere politician, equally with the pious man, ought to respect and to cherish them. A volume could not trace all their connections with private and public felicity. Let it simply be asked: Where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths which are the instruments of investigation in courts of justice ? And let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.”

And this was the father of our country. Our founders were not trying to keep faith or religion out of government, but government out of religion.

Exactly Andy