“A Central Figure of Transcendingly Absorbing Interest”: The Wilkesons at Gettysburg

ECW welcomes guest author Evan Portman

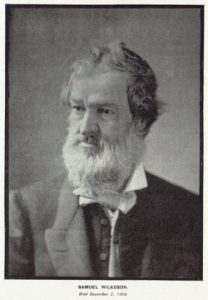

On July 1st, 1863, nineteen-year-old Bayard Wilkeson and his men of Battery G, 4th U.S. Artillery arrived in Gettysburg after a twelve-mile march from Emmitsburg, Maryland. The descendent of a prominent New York family, Wilkeson was the grandson of one of the founders of the city of Buffalo. His father, Samuel Wilkeson, had been the Washington Bureau chief for Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune while Bayard’s mother was the sister of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Seeking to secure his own place in American history, Bayard enlisted at the age of 18 when the Civil War broke out in 1861 and was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant. Having recently been promoted to 1st Lieutenant, he earned his place as the youngest battery commander on the field of Gettysburg.

Wilkeson and his battery arrived at around 11:00 am on the grounds of the Adams County Alms House, located in the northern outskirts of Gettysburg, and reported to Maj. Thomas Osborn, commander of the Potomac’s XI Corps artillery.[1] As the Confederate army continued its attacks into the midafternoon on the Federal line both north and west of the town, Osborn ordered Wilkeson and two sections of his battery to deploy from its position on the outskirts of town to support Brig. Gen. Francis Barlow’s infantry division on a small knoll further north, while 1st Lt. Charles F. Merkle took the remaining two guns about one-half mile to the northwest of the battery’s first position just east of the Carlisle Road.[2]

Just before the Confederates began their last assault of the day around 2:30 pm, as his gunners unlimbered their four Napoleon cannons, Bayard Wilkeson mounted his white horse, rode along the line of his guns, and began commanding his men to steadily and accurately fire at the enemy. As the fighting raged and the Union troops clung desperately to the knoll, Wilkeson and his horse drew the attention of Confederate Lt. Col. Hillary P. Jones’ gunners , located about 1,200 yards to the northeast of Wilkeson’s position. A shell fired from one of the Confederate guns soon struck Wilkeson’s mount and mangled the lieutenant’s right leg.[3] Displaying the same tranquility through which he had encouraged his men, the young lieutenant dismounted, pulled out a pen knife , and sawed through the tenuous threads of flesh by which his leg was still attached. Then he ordered four of his gunners to carry him on a blanket to a nearby house, only under the condition that they immediately return to man their guns.

Meanwhile, Samuel Wilkeson was serving as a New York Times war correspondent with the Union Army of the Potomac and arrived on the battlefield later that day. After witnessing the fighting of July 2nd and 3rd from Gen. George Meade’s headquarters the correspondent began a search for his son, who was presumed captured or dead. Wilkeson found the young lieutenant lifeless in the cellar of a now-bustling field hospital. The elder Wilkeson later recalled, “a Negro woman and also an Irish woman [who] occasionally visited the room in which Bayard laid, said that after a while he became weak and suffered dreadful pains, moaning and groaning and calling loudly upon his father and his mother, writhing in tortures most horrible, and so continued till about 10 o’clock when he died.”[4]

Although grim scenes such as this one occurred frequently throughout the battle, rarely was a parent able to acquire such insight into their son’s dying moments or stand in the place of his death. Oftentimes, a letter was written by a fallen soldier’s friend or comrade informing his parents of his brave and gallant death upon the battlefield. Wilkeson, however, was told a more vivid, horrific, and honest description of his son’s final hours.

However, Samuel Wilkeson also learned that his son had performed one last noble act before his death. In his last several hours, Bayard Wilkeson supposedly lent his canteen to a suffering man lying on the floor next to him. This, along with numerous other testimonials from Bayard’s superiors, among them his corps commander Oliver Otis Howard, would affirm the lieutenant’s bravery and courage for a 19-year old officer.[5]

Yet, Samuel Wilkeson would be forever tainted by the premature death of his auspicious son. On the evening of July 4th, the body of his son by his side, Wilkeson would finally begin to write his story on the events of the battle. His now famous introduction flagrantly displays the writer’s newly felt anguish and despair in its first few lines, which read, “Who can write the history of a battle whose eyes are immovably fastened upon a central figure of transcendingly absorbing interest — the dead body of an oldest born son, crushed by a shell in a position where a battery should never have been sent, and abandoned to death in a building where surgeons dared not to stay?”[6]

These words, published in the New York Times on July 6th, 1863, doubtless echoed the thoughts and feelings of hundreds of families across the nation, who, after another battle, were again left wondering whether the cost of the war justified the cause. However, Samuel Wilkeson would be the first to recognize the significance of his son’s sacrifice in what he termed the “second birth of freedom in America.” While Samuel Wilkeson went on to found his own newspaper in 1869, the premature loss of his eldest son would continue to plague the family.

————

Works Cited

[1] Harry Pfanz. Gettysburg – The First Day (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 234-236.

[2] Bert Barnett. “’If Ever Men Stayed By Their Guns’ Leadership in the 1st and 11th Corps Artillery on the First Day of the Battle of Gettysburg,” I Ordered No Man to go Where I Would Not go Myself: Leadership in the Campaign and Battle of Gettysburg: Papers of the Ninth Annual Gettysburg National Military Park Seminar, 92-93.

[3] Bert Barnett. “’If Ever Men Stayed by Their Guns’,” I Ordered No Man to go Where I Would Not go Myself, 92-93.

[4] Wilkeson, Samuel. “The Death of Bayard Wilkeson, Announced to the Family in Grim Detail by His Father 5 Days After It Occurred.” The Raab Collection, 2019.

[5] Samuel Wilkeson. “The Death of Bayard Wilkeson, Announced to the Family in Grim Detail by His Father 5 Days After It Occurred.” The Raab Collection, 2019.

[6] Wilkeson, Samuel. “Details from our Special Correspondent.” New York Times reports the Battle of Gettysburg, Dickinson College, 1863.

Barnett, Bert. “’If Ever Men Stayed By Their Guns’ Leadership in the 1st and 11th Corps Artillery on the First Day of the Battle of Gettysburg.” In I Ordered No Man to go Where I Would Not go Myself: Leadership in the Campaign and Battle of Gettysburg: Papers of the Ninth Annual Gettysburg National Military Park Seminar, 81-100. National Park Service, 2002.

Wilkeson, Samuel. “Details from our Special Correspondent.” New York Times reports the Battle of Gettysburg, 7 July 1863, Dickinson College.

Wilkeson, Samuel. “The Death of Bayard Wilkeson, Announced to the Family in Grim Detail by His Father 5 Days After It Occurred.” The Raab Collection, 2019.

Pfanz, Harry. Gettysburg – The First Day. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

http://npshistory.com/series/symposia/gettysburg_seminars/9/essay4.pdf

Great job, Evan!

Thanks for this story. My ancestor was with the Kryzankowski brigade north of Gettysburg on July 1. His story can be found here https://www.clevelandcivilwarroundtable.com/the-great-battle-of-gettysburg/.

good work Evan. its not often one gets to use the word “unlimbered” in a sentence. Ya taught me something there and also did an excellent job of bringing some historical detail to life in a compelling way. Sad, but true and there are lessons to be had there.

JB