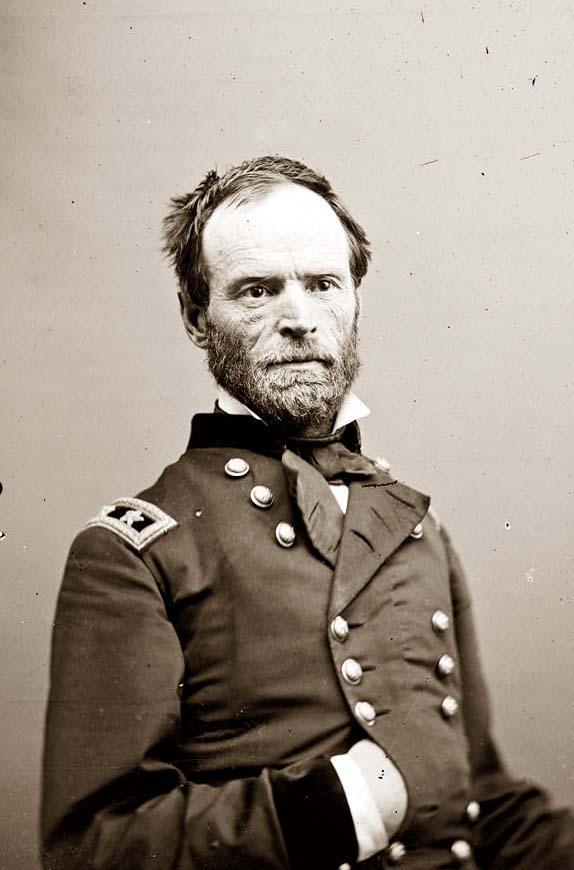

“‘Tis folly to say the people must have news”: Sherman, the Press, and Our Own Culpability

In a Feb. 18, 1863, letter to his brother, Sen. John Sherman of Ohio, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman lamented what he saw as a deterioration of American ideals. In order to defeat the Confederacy, he feared that the United States government was sinking to the Confederacy’s level.

“We have reproached the South for arbitrary conduct in coercing her People. At last we find we must imitate their example,” he wrote. “We have denounced their tyranny in filling their armies with conscripts. Now we must follow her example. We have denounced their tyranny in suppressing freedom of speech and the press, and here too in time we must follow her Example. The longer it is deferred the worse it becomes.”

This set Sherman off on one of his frequent tirades against the press. Sherman was famously no fan of reporters. “I hate newspapermen,” he once attested. “They come into camp and pick up their camp rumors and print them as facts. I regard them as spies, which, in truth, they are. If I killed them all there would be news from Hell before breakfast.”

His February letter to his brother laid out some specific grievances. As I read through them myself, Sherman’s 1863 concerns struck an eerie resonance with complaints I sometimes hear from modern audiences:

Who gave notice of McDowell’s movement on Manassas, & enabled Johnston to reinforce Beauregard so that our army was defeated?

The Press.

Who gave notice of the movement on Vicksburg?

The Press.

Who has prevented all secret combinations and movements against our enemy?

The Press.

Who has sown the seeds of hatred so deep, that Reason, Religion and Self interest cannot eradicate them?

The Press.

What is the real moving cause in this Rebellion?

Mutual hatred & misrepresentations made by a venal Press.

In the South this powerful machine was at once scotched and used by the Rebel Government, but at the North was allowed to go free. What are the results? After arousing the passions of the people till the two great sections hate each other with a hate hardly paralleled in history, it now begins to Stir up sedition at home, and even to encourage mutiny in our armies.

What has paralyzed the Army of the Potomac?

Mutual jealousies kept alive by the Press.

What has enabled the enemy to combine to hold Tennessee after we have twice crossed it with victorious armies? What defeats and will continue to defeat our best plans here and elsewhere?

The Press.

I cannot pick up a paper but tells of our situation here, in the mud, sickness, and digging a canal in which we have little faith. But our officers attempt secretly to cut two other channels, one into Yazoo by an old Pass, and one through Lake Providence into the Tensas, Black, Red &c., whereby we could turn not only Vicksburg & Port Hudson, but also Grand Gulf, Natchez, Ellis Cliff, Fort Adams and all the strategic points on the Main River. The busy agents of the Press follow up and proclaim to the world the whole thing. Instead of surprising our enemy, we find him felling trees & blocking passages that would without this information have been in our possession. All the real effects of surprise are lost. I say with the Press unfettered as now, we are defeated to the end of time.

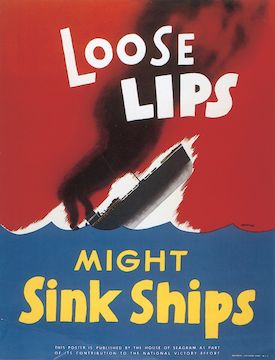

Tis folly to say the people must have news. Every soldier can and does write to his family & friends & all have ample opportunities for so doing. This pretext forms no good reasons why agents of the Press should reveal prematurely all our plans & designs. We cannot prevent it. Clerks of steamboats, correspondents in disguise or openly attend each army & detachment. And presto! Appearing in Memphis & St. Louis are minute accounts of our plans & designs. These reach Vicksburg by telegraph from Hernando & Holly Springs before we know of it.

The only two really successful military strokes out here have succeeded because of the absence of newspapers or by throwing them off the trail. Halleck had to make a simulated attack on Columbus to prevent the Press giving notice of his intended move against Forts Henry & Donelson. We succeeded in reaching the Post of Arkansas before the Correspondents could reach their Papers. Now in war, it is bad enough to have a bold daring enemy in great strength to our front without having an equally dangerous & treacherous foe within. I know if the People of the United States could see & realize the Truth of this matter they would agree to wait a few days for their accustomed batch of exciting news rather than expose their sons, brothers & friends as they inevitably do to failure and death.

Of course I know the President & Congress are powerless in this matter & we must go on till perpetual defeat & disaster point out one of the Chief Causes.

At the core of everything Sherman complains about—and justly so in most cases, I think—lies a questionable set of journalistic ethics. Today, we might couch Sherman’s central concern as a balance between the public’s right to know versus national security. Sherman puts that in the starkest terms, too: he thinks people would gladly suspend their “right to know” for a few days if they understood that “knowing” put the lives of their loved ones in mortal risk.

Most journalists I know today—and, because I’m a former journalist myself and I teach in a journalism program, there are many—understand the responsibilities of their job and hold themselves to a high ethical standard. That focus on ethics has been central to the approach we take, for instance, in the journalism program where I teach.

But business concerns do crop up that trump the traditional community service function of news outlets—forces completely out of the hands of individual reporters who are subject to the whims of their employers.. Cable television programs do inflame viewers’ passions for no other reason than to build and maintain audiences that rake in bigger ad revenues. Online news outlets do use titillation and click-bait to drive reader interaction. The tabloids do love a good celebrity feud and “mutual jealousies” because readers love them. Sherman’s “misrepresentations” are today’s “Fake News,” meant to serve propaganda, not informational, functions.

Such criticisms have become favorite mantras of people disaffected with the media, but it’s also a form of scapegoatism. After all, it’s easier to blame the media for all this trouble than it is ourselves. It’s easy to forget how complicit most of us are in any sordid media mess.

The media offer click-bait and titillation and outrage because we, as a society, keep consuming it. The media is only giving the audience what it wants. If people tuned out and turned off, if they didn’t click, if they spent their money on credible news rather than incredible entertainment and outrage, then the marketplace would force media companies to change. But because media consumers don’t change, what incentive does the media have to?

In Sherman’s time, newspapermen were trying to sell papers. It’s no different today for cable, digital, or print journalism except that there’s a lot less actual paper. But the audiences—and overall demand—is bigger than ever. Sherman suggested that a greater self-awareness on the part of newspaper readers would help fix the problem, and so it remains today.

Sherman remain pessimistic overall, though, as was his general nature. He projected a grim outcome for this depressing dilemma, lamenting “perpetual defeat & disaster….”

As the public did in Sherman’s day, we have a choice in the matter. Our media consumption does not have to lead us to defeat and disaster—or divisiveness. Through our own behavior, we can choose otherwise.

Sherman was realistic, not pessimistic. The highest casualties of the war were yet to come. The end was farther in the future than Bull Run was in the past. Vicksburg campaign would require another 4 months.

More troops on both sides meant more deaths.

It was not clear how the war could end.

Even big battles like Shiloh and Antietam were followed by regroup and repeat. Battles would not end the war. Occupations (like Memphis) were plagued by partisan attacks and required large armies..

It would be another year before Sherman made his march through Mississippi and proved the strategy that on a larger scale would end the war. Only destruction on a larger scale- marches through Georgia, the Carolinas and the Shenandoah (Sheridan) would do what battles did not, force an end to the war.

I agree, he was realistic about his assessment of the war and all that. When I describe him as pessimistic, it’s because he was a “glass half-empty” kinda guy.

Sherman had seen good competent generals drummed out of service when they suffered setbacks. Sherman had earlier complained about press attacks on McDowell.

In 1861, newspapers attacked Sherman calling him insane. At the time insanity was an unmentionable disgrace. No wonder he held a grudge.

Sherman had given an estimate of the number of troops needed to win the war in the West that was an order of magnitude higher than troop levels in 1861, a number that shocked the press and the politicians. Pessimist? Insane? Realist? Sherman’s 1861 estimate was quite close to the number of troops in the west in 1865.

I think your central point is partly true. People are responsible for what they read and watch. However, I think really smart people work for media corporations (sometimes in government) and know how to masterfully persuade large numbers of people. It’s a little easy to blame the masses, when they don’t know any better and this includes lots of highly educated people, all of us really. Perhaps we are heading towards a new paradigm where we are all more enlightened about what the news is, but I doubt it. Has the news really ever changed? It’s always been about making mullah (as we all do in some fashion) or gaining political power to control the purse strings. What’s different today is simply the medium: the internet.

Interesting times, but I hope it doesn’t turn into mass oppression or violence.

My father was a newspaper reporter and some received criticism. Because people don’t like bad news about themselves, especially if its true.

19th century newspapers were often political mouthpieces. They resemble political blogs today, more than professional journalism.

Great article Chris