“Sublime but Dismal Grandeur”: The Battle of Jackson, Mississippi

“There are some slight errors in history in regard to the capture of Jackson, which I will take opportunity to correct,” declared Samuel C. Miles, a veteran of the 8th Wisconsin Infantry, in a 1893 letter to the National Tribune. Miles was an inveterate letter writer, and among veterans of the regiment, he in particular loved to refight their old battles. Between 1893 and 1897, Miles took up his pen no fewer than 15 times to correspond with The National Tribune’s “Fighting Them Over” section, a column where veterans could refight with pen the battles they first fought with rifles.

In the summer of 1893, Miles turned his attention to the regiment’s action during the battle of Jackson, Mississippi. The Tribune printed the reminiscences as a two-part account on July 27 and August 3.

Miles’s hyperbolic writing style is, in its way, a delight to read. His accounts are expansive, grand, larger than life. Everything seems bigly.

Miles’s regiment, the 8th Wisconsin, served in Brig. Gen. Joseph Mower’s Second Brigade in Brig. Gen. James Tuttle’s Third Division in Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s XV Corps. The regiment had as its mascot a live bald eagle named “Old Abe,” named after the president of the United States, which gave the regiment and the brigade its “Live Eagle” nickname. Miles—in a biography he published of Old Abe, described the eagle as a “fine specimen of our national emblem . . . [who] so grandly shared all the privations, exposures and perils of the grand and triumphant campaigns and over thirty battles. . . .”

On the night of May 13, Sherman’s corps advanced northeast from Raymond, Mississippi, toward the state capital—“Fighting Joe Mower’s invincible Second (Live Eagle) Brigade in the lead, skirmishing with the enemy and steadily driving them toward Jackson,” crowed Miles. To the north, Maj. Gen. James McPherson advanced on Jackson from the northwest. The two wings of the army had coordinated closely to time their arrival in Jackson as simultaneously as possible.

Awaiting them were about 6,000 Confederates under the titular command of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, recently arrived from his headquarters in Tennessee. But no sooner had Johnston disembarked from his train than he took one look at the situation and immediately set to work on plans to evacuate the city. As Johnston packed up, he appointed Brig. Gen. John Gregg to command of the defenses and buy as much time for Johnston and the army’s supplies to make their escape as possible.

Battle finally opened in earnest just after dawn. The day’s heaviest fighting occurred on McPherson’s front, but to read Miles’s account—told in a voice that would make later pulp novelists proud—Sherman’s men experienced the full drama and trauma of war. Just after dawn, the men in Sherman’s column could hear “the heavy booming of cannon away to the left, where McPherson was engaging the enemy,” Miles wrote, “with the shells bursting around us, the rapid fire of musktey [sic] and a storm of leaden hail sweeping by, blending with the almost incessant lightning and thunder crash of heaven’s artillery, with the down-pouring torrents from the clouds—all combine to make a scene of sublime but rather dismal grandeur.”

Confederates made a smart defense along a rain-swollen creek Sherman’s men could not cross, forcing a bottleneck at the bridge where the road crossed the stream. Sherman’s troops forced passage when the Confederates failed to torch the bridge, perhaps because the wood was too drenched from the storm. As Federals flooded across the span, the Confederates fell back to the works at the edge of town. A number of artillery pieces bolstered the works, manned by eager if slightly trained citizen volunteers.

Rather than attack head on, Sherman sent a flanking force that eventually made its way unopposed unto the city. At about this time, the skies began to clear, and the situation directly in front of the Confederate works looked clearer, too. “The rain is now over, and the bright sun begins to pierce the fast-fleeting clouds and cheer the thoroughly-drenched soldiers with his bright rays,” wrote Miles, apparently ebullient that his Vitamin D deficiency would soon be alleviated.

Despite the play of Confederate artillery, Mower, at the center of the Federal line, began to suspect that not all was as it appeared before him. Then came the sound of cheering from somewhere in the Confederate position—the huzzahs of the flanking force as it began to capture Confederate artillery positions from the rear. Gen. Tuttle decided to send his entire division—Mower, Matthies, and Buckland—forward.

“We meet the heavy artillery fire from the enemy’s line of city defenses along the ridges and high ground across the open fields,” Miles wrote, using present tense to underscore the immediacy of the action:

but without delay Fighting Joe issues orders to his regimental commanders to deploy in line as they advance under cover of the timbered ridges along the open fields. Above the battle’s din of booming cannons’ roar and bursting shell the command rings forth along the line, ‘Attention! Fix bayonets—Forward—Double-quick—Now, steady, boys! Keep your alignment—March!’ And now out upon the open field sweeps that invincible line of loyal blue and vengeful glistening steel . . . [toward] the unquailing, even line of valiant defenders. . . .

Mower’s four regiments made up the center of the attack. “[B]eneath one of those four stands of proudly-waving regimental banners,” recalled Miles, “the War Eagle Old Abe’s valiant form and spreading wings proclaim to that line of rebel gray that they are vainly resisting a foe who never knew defeat.” Another of Old Abe’s biographers (and there were a few, Miles among them) later described the eagle as “all spirit and fire. He flapped his pinions and sent his powerful scream high above the din of battle.”

In his account, Miles hits his stride during the sprint to the Confederate earthworks:

On sweeps the irresistible line of blue, undismayed and unchecked by the terrible storm of lead and iron which thins their ranks and strews the field with mangled slain. With their thundering Union cheer pealing clear above the battle’s horrid din, as their undaunted line sweeps up that last homestretch of bristling trench and parapet-crowned hights [sic], is it any wonder that when they leap over those defenses they find most of that chivalrous line in full flight for safer localities, while those brave men who choose to stay, either too brave to run away, that they may fight another day, or dare not leave the shelter of their trenches to turn their backs toward the charging foe, are gobbled within their defenses?

In fact, Confederates had largely abandoned the works already on Gregg’s orders, but that hardly mattered to Miles in his recollection of events. “Having cleared and captured the defenses of Jackson on the southwest,” Miles reported, “the Live Eagle Brigade pursues the retreating Confederates through the streets to the north . . . and the whole Confederate force is immediately in hasty retreat in the direction of Canton. . . .” By his account, the thundering success of Sherman’s assault, not Gregg’s orders, “compelled the hasty evacuation of those in front of McPherson’s Corps on the Clinton road. . . .”

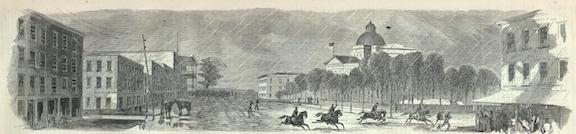

The regiment’s route of march brought them to the Mississippi statehouse “where the Confederate flag is arrogantly waving above the State capitol dome,” Miles snarled. “It does not take the Color Guard of the Live Eagle regiment many minutes to enter the building and haul down the Secession rag, and . . . the Stars and Stripes of the 8th Wis. are proudly waving in its place.”

This incident, over time, became a source of great tension among veterans of the Army of the Tennessee. Many units claimed the honor of raising their flag over the city, and the National Tribune served as a key battleground for fighting over that particular distinction. Miles’s two-part piece was written as his salvo in the battle. “[A] capture of a State Capitol and a Confederate flag floating thereon was not a matter of such common occurrence as to be considered unworthy of record,” he insisted. Several other members of the regiment, in their own writings, corroborated Miles’s assertion, but no definitive proof has ever emerged.

As any soldier who has only a glimpse of the action on his immediate front, Miles’s account of the battle of Jackson gives great weight to the fighting by Mower’s brigade, even to the short shrift of other brigades in the division (Buckland’s brigade, for instance, sustained heavy, straight-on artillery fire). However, McPherson’s corps, fighting along the Clinton road, bore the greatest brunt of the battle. The Federals suffered exactly 300 casualties, with 265 of them on McPherson’s front.

The Confederates, meanwhile, suffered some 845 casualties and the stinging loss of 17 guns, most of which were captured by Tuttle’s division as it swept into the works following Gregg’s withdrawal.

Although the May battle of Jackson was not as pivotal as, say, Port Gibson or Champion Hill, it provided Grant with much-needed breathing room by dispersing Johnston’s potential threat in the Federal rear. It also hampered the Confederacy’s ability to reinforce or resupply the army in Vicksburg by cutting one of the necessary rail lines for moving in troops or supplies. Finally, the fall of the state capital—the third to fall in the war—provided a shocking blow to morale throughout the South.

“[T]he city still stands,” Miles wrote in 1893, capturing in present tense the moment of his brigade’s departure in 1863 but reflecting, through his sense of drama, something larger, too, “and her magnificent capitol, with all its valuable records, where foul treason was first ordained, is left unharmed, as a monument of their outraged country’s forbearance and the generosity of their hated Yankees and conquerors, a monument to their shame. . . .”