A Chronology of the Confederacy’s 1862 Counterstrokes

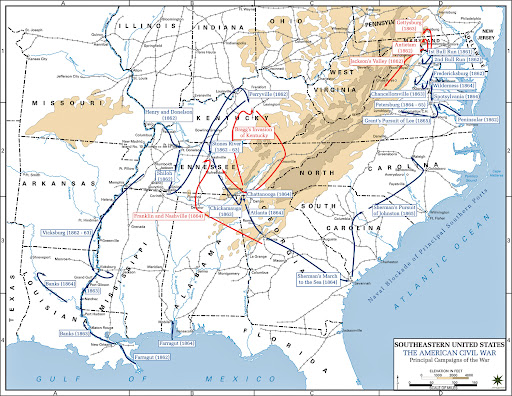

Several months ago, I crossed an item off my Civil War bucket list: visiting the Perryville battlefield. While at the visitor center, I watched a video which put the Confederate invasion of Kentucky into the larger context of the war. This orientation video showed seven red arrows moving north in the summer and fall of 1862: seven Confederate offensives to seize the initiative in the Civil War’s second summer and gain the Confederacy’s independence. I was familiar with many of these Confederate counteroffensives but was surprised to see seven. After some digging and help from ECW colleagues (thanks Chris Kolakowski and Phill Greenwalt), I determined the seven red arrows represented the following campaigns and battles: the campaign to recapture Baton Rouge, Louisiana; the Maryland Campaign; the Kanawha Valley Campaign; Kirby Smith’s and Braxton Bragg’s campaign into Kentucky; the Iuka-Corinth Campaign; and the Prairie Grove Campaign.

The more I looked into these seven counteroffensives, the more I was surprised to see how so many of them had important events happening simultaneously with one another despite those events taking place hundreds of miles apart. Below is the chronology of these seven Confederate counteroffensives and the political and military events related to them. As with any military campaign, the Confederacy sought to achieve political means via these offensives, and the political aspect of these campaigns should be considered accordingly.

July 27, 1862: John Breckinridge’s force of 5,000 Confederates leaves Vicksburg in preparation for its attack on Baton Rouge.

July 31, 1862: Braxton Bragg and Kirby Smith meet in Chattanooga, Tennessee to develop a plan meant to drive Union forces from Tennessee.

August 3, 1862: General-in-Chief Henry Halleck orders Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac off the Virginia Peninsula and north to Northern Virginia to unite with Maj. Gen. John Pope’s Army of Virginia.

August 5, 1862: Breckinridge’s force attacks the Union defenders of Baton Rouge, who repulsed the Confederate attack.

August 9, 1862: Pope’s Army of Virginia engages Stonewall Jackson’s command at Cedar Mountain, Virginia.

August 13, 1862: Orders issued from Army of Northern Virginia headquarters to move the army from Richmond toward Gordonsville.

August 14, 1862: The Army of the Potomac begins departing its camp at Harrison’s Landing.

August 16, 1862: Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith’s Army of Kentucky crosses the Cumberland Mountains and enters Kentucky.

August 18, 1862: Pope pulls his army back to the north bank of the Rappahannock River to await reinforcements from the Army of the Potomac.

August 21, 1862: Maj. Gen. Braxton Bragg’s Army of the Mississippi crossed the Tennessee River in preparation for its movement north to Kentucky. In the Trans-Mississippi theater of war, Confederate Gen. Thomas Hindman receives orders to piece together an army of disparate Confederate units in the region; Hindman’s ultimate goal was to regain control of Missouri.

August 22, 1862: J.E.B. Stuart raids Pope’s supply train at Catlett’s Station.

August 23, 1862: The Battle of Big Hill is the first engagement of the Kentucky Campaign.

August 25, 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s flank march around the right of Pope’s Army of Virginia begins.

August 26, 1862: Jackson’s force severs Pope’s supply line, the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, at Bristoe Station.

August 27, 1862: Jackson’s force captures Manassas Junction and repulses attacks there by the 2nd New York Heavy Artillery and the Army of the Potomac’s New Jersey Brigade. Richard Ewell’s rearguard at Bristoe Station engages a Federal force under command of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker in the Battle of Kettle Run.

August 28, 1862: The Battle of Second Manassas begins at Brawner’s Farm. Longstreet’s wing of the Army of Northern Virginia pass through Thoroughfare Gap, placing the two wings of the army within a day’s march from one another. Bragg’s army crosses Walden’s Ridge and moves into central Tennessee.

August 29, 1862: The second day of the Battle of Second Manassas. The Battle of Richmond, Kentucky, begins.

August 30, 1862: Two Confederate armies led by Robert E. Lee and Kirby Smith are victorious in two sweeping victories at Second Manassas, Virginia, and Richmond, Kentucky.

August 31, 1862: Pope gathers his army in the defenses of Centreville, Virginia. Lee begins a flanking march to interpose his army between Pope’s and Washington, DC. Federals evacuate Fredericksburg, Virginia, and lose a considerable number of supplies in the process.

September 1, 1862: The Second Manassas Campaign ends with the Battle of Chantilly, Virginia.

September 2, 1862: Maj. Gen. McClellan assumes command of the Union forces in and around Washington, DC. Union forces evacuate Winchester, Virginia. Smith’s Army of Kentucky occupy Lexington. Martial law is declared in Cincinnati, Ohio, and Covington and Newport, Kentucky, in anticipation of a Confederate movement to the Ohio River.

September 3, 1862: Lee writes President Jefferson Davis, “The present seems to be the most propitious time, since the commencement of the war, for the Confederate Army to enter Maryland.” Portions of Smith’s command occupy the Kentucky state capital at Frankfort.

September 4, 1862: The Army of Northern Virginia begins crossing the Potomac River into Maryland (the crossings continued until September 7).

September 5, 1862: Bragg proclaims Alabama “is redeemed” from his headquarters at Sparta, Tennessee. Buell’s Army of the Ohio continues its march out of northern Alabama en route to Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

September 6, 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s divisions occupy Frederick, Maryland, in the van of the Army of Northern Virginia. Federal forces evacuate their stores at Aquia Creek. General William Loring’s 5,000 men leaves Narrows, Virginia, and begin their march to Charleston, (West) Virginia.

September 7, 1862: McClellan joins the Army of the Potomac in the field in Maryland. Jefferson Davis writes to Lee, Bragg, and Smith, “the Confederate Government is waging this war solely for self-defence, that it has no design of conquest or any other purpose than to secure peace and the abandonment by the United States of its pretensions to govern a people who have never been their subjects and who prefer self-government to a Union with them.”

September 8, 1862: Lee writes a proclamation to the people of Maryland.

September 9, 1862: Lee issues Special Orders No. 191, dividing his army with the purpose of subduing the Union garrisons in the Shenandoah Valley at Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

September 10, 1862: The Army of Northern begins departing Frederick, Maryland.

September 11, 1862: Portions of Lee’s army occupy Hagerstown, Maryland. Pennsylvania’s governor, Andrew Curtin, calls for fifty thousand militia to defend the Keystone State. Confederate units get within seven miles of Cincinnati, Ohio. Union and Confederate forces skirmish in the Kanawha River Valley in western Virginia.

September 12, 1862: The vanguard of the Army of the Potomac enters Frederick, Maryland. Federals evacuate Martinsburg, (West) Virginia.

September 13, 1862: Two soldiers from Indiana find a lost copy of Special Orders No. 191 outside Frederick, Maryland. Loring’s command defeats a Union force led by Col. Joseph Andrew Jackson Lightburn at Charleston, (West) Virginia; Confederate soldiers capture the city.

September 14, 1862: The Army of the Potomac wins the Battle of South Mountain; approximately 5,000 soldiers become casualties. James Chalmers’ assault against the Union defenders of Munfordville, Kentucky is repulsed. Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio reaches Bowling Green, Kentucky. Sterling Price’s Confederates occupy Iuka, Mississippi. British Prime Minister Viscount Palmerston writes Foreign Minister Lord John Russell that if the Confederate victory at Second Manassas leads to the capture of Washington or Baltimore, it might be time for Britain to mediate an end to the war.

September 15, 1862: Harpers Ferry’s garrison of approximately 12,500 soldiers surrenders to Stonewall Jackson’s Confederates, marking the largest surrender of United States soldiers in the Civil War. Kirby Smith’s forces make a brief appearance in front of Covington, Kentucky.

September 16, 1862: The two opposing armies gather along Antietam Creek outside of Sharpsburg, Maryland. Bragg’s Army of the Mississippi arrives opposite Munfordville, Kentucky.

September 17, 1862: The single bloodiest day in American history. The Battle of Antietam leads to 23,000 casualties between the two armies. Colonel John Wilder’s Union garrison at Munfordville, over 4,000 men, surrenders to Bragg’s army. George Morgan’s Union garrison abandons Cumberland Gap and begins its long march north. Russell writes to Prime Minister Palmerston and agrees “the time is coming for offering mediation to the United States Government, with a view to the recognition of the Independence of the Confederates.”

September 18, 1862: Lee begins his withdrawal across the Potomac River this night. Bragg makes a proclamation to Kentuckians that his army came not to conquer but to free Kentucky.

September 19, 1862: Federals under Ulysses S. Grant and William S. Rosecrans are victorious against Sterling Price’s Confederates at Iuka, Mississippi. In Maryland, McClellan’s army pursues Lee’s to the Potomac River.

September 20, 1862: The Battle of Shepherdstown, (West) Virginia, ends the Maryland Campaign.

September 22, 1862: Abraham Lincoln announces the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

September 23, 1862: With the news of the Confederate defeat in Maryland not yet having reached England, Prime Minister Palmerston writes, “the iron should be struck while it is hot” regarding offering mediation to the United States and Confederate States governments.

September 25, 1862: Buell’s Army of the Ohio occupies Louisville, Kentucky.

September 29, 1862: General Jefferson C. Davis shoots Gen. William “Bull” Nelson in Louisville, Kentucky. Earl Van Dorn’s Army of West Tennessee, 22,000 strong, departs Ripley, Mississippi headed for Corinth, Mississippi.

October 1, 1862: Bragg and Smith meet in Lexington, Kentucky. Buell’s Army of the Ohio begins its march east from Louisville.

October 3, 1862: Van Dorn and Price begin their assault against the Union defenses of Corinth, Mississippi.

October 4, 1862: The Battle of Corinth ends in a Confederate repulse. They withdrew northwest from Corinth. Kentucky’s Confederate governor, Richard Hawes, is inaugurated at Frankfort, Kentucky.

October 5, 1862: The Corinth campaign ends with fighting at Davis Bridge, Tennessee.

October 8, 1862: The Battle of Perryville, the largest and bloodiest battle fought in the state of Kentucky, leads to Bragg’s repulse and decision to withdraw from the Bluegrass State.

October 13, 1862: Bragg’s Army of the Mississippi begins its march out of the state in the direction of Cumberland Gap.

October 14, 1862: Democrats make gains in midterm elections in Ohio, Indiana, and Pennsylvania.

October 18, 1862: John Hunt Morgan’s cavalry command capture Lexington, Kentucky.

October 19, 1862: Bragg’s army reaches the vicinity of Cumberland Gap.

October 21, 1862: Jefferson Davis writes to one of his commanders in Missouri of plans to have a combined Confederate force drive the enemy from Tennessee and Arkansas.

October 24, 1862: The Army of the Mississippi successfully completes its passage through Cumberland Gap and returns to Tennessee. William S. Rosecrans replaces Buell in command of the newly formed Department of the Cumberland.

October 28, 1862: Loring’s army withdraws from Charleston, (West) Virginia, ending the six-week Confederate occupation of the city.

October 30, 1862: France’s Emperor Napoleon III proposes that France, Russia, and Great Britain jointly mediate an end to the American Civil War.

November 4, 1862: Democrats make gains in midterm elections.

November 12, 1862: The British Cabinet rejects France’s call for mediation. This, coupled with Russia’s earlier refusal to join, kills the scheme.

November 28, 1862: Confederate forces are defeated at Cane Hill, Arkansas, “giving the Federals a momentary edge in the Trans-Mississippi fighting,” according to historian E.B. Long.

December 1, 1862: Thomas Hindman gathers 12,000 Confederates near Van Buren, Arkansas.

December 3, 1862: Hindman’s army departs their camps and begins marching to strike James Blunt’s isolated Federal division.

December 7, 1862: Hindman attacks Blunt’s force at Prairie Grove, Arkansas. Francis Herron’s men reinforced Blunt’s command and together, they repulsed Hindman’s Confederates. Hindman’s men withdrew and returned to their camps from where they began the campaign.

Thanks for the chronology! Leaving September 8 for a trip to visit 1861-62 battlefields in Tennessee and Kentucky (and nearby places like New Madrid and Corinth). This will come in handy.

These seven counter strokes- offensives – should be carefully considered in any discussion of a “turning point” in the Civil War. My own sense is that the CSA – in light of the outcome of these offensives – lost the war in 1862. Thank you for this very helpful chronology!

You probably already saw this, but the Perryville Civil War Battlefield Website has a link to an excellent article by Dr. Robert S. Cameron entitled “The Road to Perryville: The Kentucky Campaign of 1862” in which he asserts that Bragg intended to have Breckinridge’s force follow him to Kentucky to assist in troop recruitment there, but due to his absence from the Mississippi theatre and failure to issue clear orders (what else is new) to Van Dorn, Price, and Breckinridge, Van Dorn independently decided to send Breckinridge towards Baton Rouge, causing his Kentucky troops to entirely miss the Kentucky campaign!

Also, Confederate recruiting officers & partisan leaders were hard at it in Missouri in August-September. There were battles at Lone Jack, Independence, Kirksville, Vassar Hill, Moore’s Mill, and Newtonia, just to name a few. They took advantage of backlash against heavy-handed Union occupation & the militia enrollment decrees.

Tony, what’s the best book about this period in Missouri?

Gray Ghosts of the Confederacy covers guerrilla fighting in MO thru the whole war including that tumultuous summer. There are also a couple of books that focus on Col Joe Porter’s operations in that summer in NE MO. I’d have to dig for their titles.

Thanks, Tony! Will find a copy of that book….

Excellent post! As a grad of nearby Centre College, Perryville ( and Dr Hecks Civil War course) have a special place in my heart.

The year 1862, viewed as a whole, does appear to be the true “high water mark” of the Confederacy, when they mounted offensives across the map (across the theaters of war). Preceding your chronology above, there was also Van Dorn’s intended movement into Missouri (ultimately targeting St. Louis) that was stopped short at the Battle of Pea Ridge in early March. And, farther west, the ill-fated Confederate invasion of New Mexico, culminating in the Battle of Glorieta in late March.

I saw the same video this week and was struck by the same point. I came home and resolved to investigate. Thanks for doing that. For me, the interesting thing is that I doubt this was an overall CSA strategy. But, from my own work experience, some things can look like they are coordinated, but are just chance.