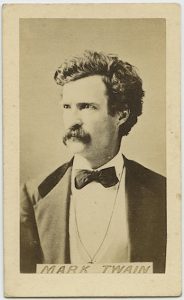

Under Fire: Mark Twain’s Experiences in the Confederate Militia

As I explored in a previous blog, Mark Twain/Samuel Clemens lived a complex life. One of the lesser-known facets of his life is his limited service during the American Civil War. Though it may not be a purely non-fiction retelling of his service, Twain recorded his first “combat” experience in the militia in “The Private History of a Campaign That Failed.” I found this short story a very compelling and interesting, if not also unusual, tale of the Civil War. It isn’t written as a traditional story of the war, but instead occupies a unique niche. Rather than a tale of tactics or great generals such as Michael Shaara’s Killer Angels or an individual’s tale such as Stephen Crane’s Red Badge of Courage, “The Campaign that Failed” instead feels a great deal as if one is reading The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. The story reads more as a exploration of childhood adventure than a tale of war. War is often portrayed as adventure in Victorian Era writings; but this story is different. Rather than an adventure involving maturing into manhood that many of Twain’s tales described, the story is portrayed as simply a childish adventure.

When first encountering what could have been enemy troops in a barn, the group elects to “flank” the barn rather than storm it. At every rumor of enemy forces, the group retreats to some other camp rather than meet the enemy. Their days in camp are described as such: “We had some horsemanship drill every forenoon; then, afternoons, we rode off here and there in squads a few miles, and visited the farmers’ girls, and had a youthful good time, and got an honest good dinner or supper, and then home again to camp, happy and content. For a time, like was idly delicious; it was perfect; there was nothing to mar it.” That isn’t a story of glory or hardship; that is the story of innocent boyhood adventures.

That isn’t to say that this story was devoid of any serious substance; several thoughtful statements are made throughout the story. Twain discusses the difficulty many Confederate units had with insubordination. Sprinkled throughout the story are incidences of men refusing to go on picket duty, refusing to follow orders, or even arguing about who had authority over whom. Twain only wrangles a partner for picket duty by offering to trade ranks temporarily! He explains this rather serious issue by saying that the camps all over the state were “composed of young men who had been born and reared to a sturdy independence, and who did not know what it meant to be ordered around by Tom, Dick, and Harry, whom they had known familiarly all their lives.” This issue of independence plagued smaller units during the beginning of the Civil War. Primarily, however, Twain discussed a man that his “company” shot and killed. Fearing enemy combatants, the group fired upon a plainly dressed man who strayed near their camp by accident. Looking back on what the militia might have called their first battle, Twain later spoke to other veterans about how his 15-man band came across the foe: “On the other side there was one man. He was a stranger. We killed him. It was night, and we thought it was an army of observation; he looked like an army of observation – in fact, he looked bigger than an army of observation would in the day time; and some of us believed he was trying to surround us, and some thought he was going to turn our position, and so we shot him.” Immediately after, the men are all filled with regret, saying that “if it were to do over again they would not hurt him unless he attacked them first.” Even though this first experience “under fire” was hardly a battle and the slain stranger never fired a shot, the experience stuck with Twain.

In his story, Twain turns this incident into a tale about how he felt about war, writing “that all war must be just that – the killing of strangers against whom you feel no personal animosity; strangers, whom, in other circumstances, you would help if you found them in trouble, and who would help you if you needed it.” Twain then resolved that he was not made for war, and after a little more “campaigning”, he and some of the group retire from military life while others stay and eventually learn to be real soldiers.

The full history of Clemens’s involvement in the militia is unclear. Essentially, he served in a Confederate militia in Missouri for a total of around two weeks in 1861 at the “rank” of Second Lieutenant. At a reunion of Union veterans, he flippantly mentioned it, discussing his single “battle” and stating he then “gave the Union cause a chance.” It is interesting then, to consider that a man who technically fought for the Confederacy eventually became key to the writing and publication of Ulysses S. Grant’s memoirs. All in all, it is yet another complex layer to the story of Mark Twain/Samuel Clemens.

When I was about the age as Tom Sawyer was in the book, I thoroughly enjoyed Twain/Clemens book as I could identify with his character. Also, I could free-range about town and nearby locations, mostly by bicycle, being in a small town in SW Missouri, in much the same way as Tom did. Next door neighbor Marilyn Michie was, to some degree, similar to Tom’s friend Becky for a short period of time. I read most every one of Twain’s books. When in Hawaii several years ago I found a reprint of Twain’s book of his trip to Hawaii in a Honolulu book store. I particularly recall him describing the appearance of a palm tree as resembling an umbrella which had been struck by lightning.

I’ve read that travel narrative! His notes on race are a little tone deaf but it is a nice read, like nearly everything he wrote.

Hoping for a first-hand account of Pea Ridge, or at least Blue Mills Landing, it was disappointing to read Mark Twain’s war experience… the first time. Years later, the recollection was discovered to contain nuggets of insight, helping explain the confused, proclaimed self-righteousness of the neighbor versus neighbor conflict in Missouri, which had every possibility of devolving into brutal guerrilla warfare, had it not been for the chivalric adoption of State Guard (rebel) and Home Guard (union) affiliation. Under accepted flags, bands of like-minded Guards set out to murder their opposed-view Guards with impunity, resorting to ambush, arson, food poisoning, and night raids. And while it is curious that trained river pilot Samuel Clemens joined a (suspected) State Guard infantry unit instead of offering his valuable skills to the prosecution of riverine warfare, the author, himself, addresses the issue in the work: “[I was] full of unreasoning joy to be done with turning out of bed at midnight and four in the morning for a while…”

I agree. It seems like an underwhelming service narrative until you think a little more on it.

Two week soldier. That Clemens was a funny fellow. His real service to the country was helping to get U.S. Grant’s memoir published.

The memoir really is a literary work of art. Very well written and meaningful.

I’ve had both versions of Twain’s tale sitting on the desktop of my laptop for months with the intention of posting them so readers could compare them. I’ve just been waiting for a free minute to do it.

Still waiting for that free minute…. :-p

Oops! There’s a lot to pull out of it, so I still think you should post it… when you’ve got that spare moment.

Clemens’ brother had been a Lincoln supporter. After being elected, Lincoln rewarded him by making him governor of the Nevada Territory. When his two-week “tour of duty” was over, Samuel decided to join his brother in Nevada. Thus began his career as a newspaper correspondent writing humorous accounts of the Nevada frontier.

Only Samuel Clemons would decide that a two-week military career was adequate! I should have been so insightful!