Hurrah for Homespun!

Poetry and songs that came out of the Civil War, entertaining as they are, served as a useful vehicle for rhetoric that supported their respective sides. Songs like “Bonnie Blue Flag”, “Marching Through Georgia”, “Dixie”, and “Battle Cry of Freedom” are just a few of the most widely celebrated songs of the war that contained this sort of political or ideological twist. Another, lesser known, evokes not just pro-Southern/Confederate values, but serves as a link to Revolutionary times just ninety-something years prior.

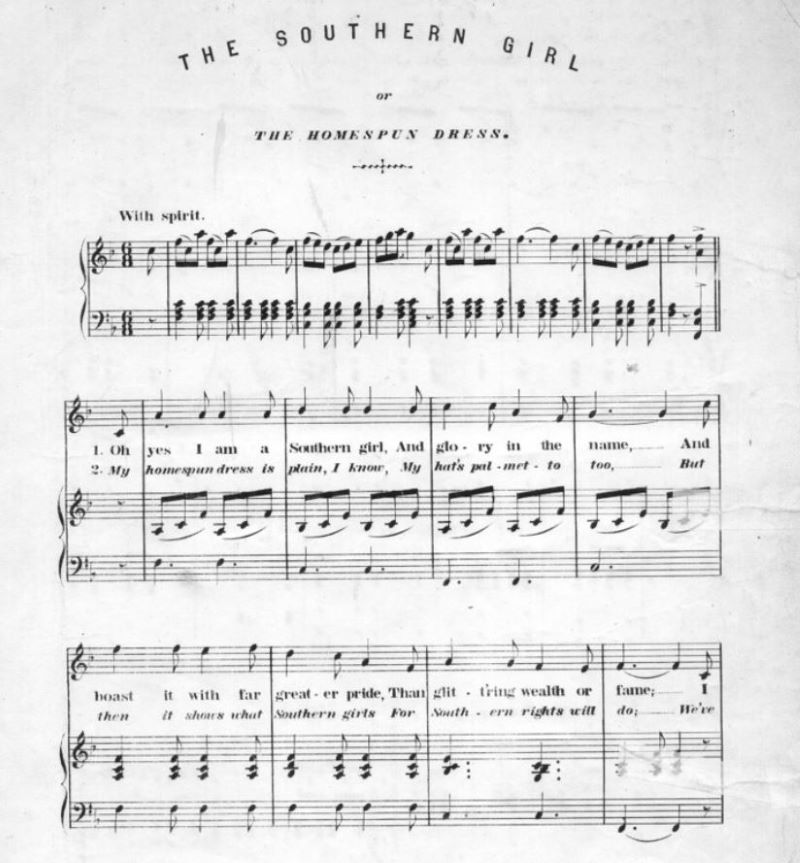

The song in reference is “The Homespun Dress” written by Georgian, Carrie Belle Sinclair, who was the niece of steamboat inventor Robert Fulton, and a volunteer nurse in Savannah’s Confederate hospitals. Born in 1839, she would have been in her early twenties during the war. Her song, ideally played to the tune of “Bonnie Blue Flag,” speaks of Southern women who proudly wear homespun. Verses promote the wearing of homespun as a mark of Confederate patriotism, scorning the finery of pearls and diamonds worn by Northern ladies, admitting to the plainness of homespun but that the act of wearing it makes a declaration of “what Southern girls for Southern rights will do.” One stanza in particular reads, “We scorn to wear a bit of silk, – A bit of Northern lace, – But make our homespun dresses up, – And wear them with a grace.”[1] The spirit of the song itself harkens back to a previous generation when the wearing of homespun made another similar political statement.

In the years leading up to America’s separation from Britain in the eighteenth century, economic as well as political independence were in the forefront of the minds of citizens and early leaders. Up to this transitory phase into independence, America had been heavily entrenched in the British system of economy. Colonies were obligated to produce raw materials that would be shipped to Britain to be manufactured into finished goods, which would then be purchased by British subjects. Laws and restrictions on local manufacturing put the American colonies at a disadvantage, making economic independence a struggle in those early Revolutionary years. To make matters more difficult, Congress agreed that nonimportation and nonexportation efforts would “obtain redress of these grievances, which threaten destruction to the lives, liberty, and property of his majesty’s subjects in North America.”[2] By depriving Britain of the raw goods America provided, they hoped to wear down Parliament into negotiations.

On the flip side, cutting off America from foreign trade amped up the pressure on newly formed American manufacturers and mechanics – producers of finished products – to produce the goods needed for survival. This didn’t really take off until after the Revolution, but until then, most manufacturing was done from the home by local families or artisans. Thus, an economic boycott of British goods was encouraged, and the homespun movement gained momentum. Language used to promote nonimportation and homespun – or general homemade goods – relied on ideas of virtue, saying that these efforts would suppress extravagance and promote frugality as colonists rejected foreign luxuries.[3] In essence, the wearing, production, and selling of homespun also declared independence from Britain as much as the Declaration did, politicizing the association with homespun. Seniors at Harvard College promised to wear homespun at graduation, despite the protests from the faculty saying that such an act would “inflame the minds of a true and loyal people” to the Patriot cause for independence.[4] Accelerating the demand for domestic goods would then compel the creation of formal manufactures, and prevent the development of “a state of the most abject slavery” at the hands of the British or any other foreign entity.[5]

During the Civil War, a parallel can be seen in the secession of the South from the North, both politically and economically, just as the American colonies separated from the mother country of Britain. These comparisons were made in contemporary times by Confederate sympathizers, declaring their own secession as a second revolution. (for a great dissection on the difference between secession and revolution, I refer you to Part 1 of the interview between Doug Crenshaw and Nathan Hall HERE ) Due to the specialization of agricultural industry in the South, citizens below the Mason-Dixon Line depended on the import of goods they did not have the infrastructure to produce, primarily from northern industrial states and from abroad. As the conflict progressed, commerce with the North became just as difficult as trading with other countries like France and Britain as the blockading of seaports commenced. Likewise, cotton and other raw materials that were exported from the South would be missed by the other countries that benefited from their trade and end up rotting on plantations or on port city docks. Just as during the Revolution, the lag in importing and exporting goods were predicted to aid the Southern cause, either by making it stronger in the way of building up domestic manufacturing on a basis of necessity, or by winning foreign recognition so the blockade may be challenged and exportation could resume.

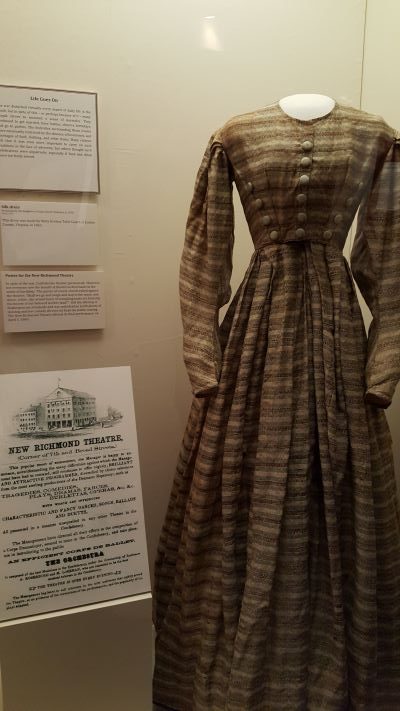

Confederate leaders, like Congress during the Revolution, called for the South to become more economically independent as they also sought political independence.[6] Just like during the Revolution, concepts of virtue and patriotism were presented to challenge any aversions to wearing or producing homespun. The Southern Illustrated News reported in 1862 that “not five out of five hundred ladies would be caught in the street in a homespun dress.”[7] In response, Confederate President Jefferson Davis called for women to set aside their vanity, stating that homespun was “becoming to them” and that they should “prove to the world that the Southern woman’s principle and patriotism are not subordinate to the pride of the eye.”[8] Coupled with the patriotic reasons for producing homespun, Davis hit on the idea that women viewed homespun as plain, unattractive, and least preferred against other fashionable styles of the day. This effort to appeal to women’s preoccupation with fashion and appearance was nothing new. Decades earlier, Elkanah Watson understood the importance of women in the early republic textile industry and endeavored to appeal to women’s presumed vanity by creating homespun “fashion shows” to be held at his agricultural fairs. These cloth shows were designed to cast women as both producers and consumers of American-made fabrics.[9]

In essence, the Confederate government instilled the economic and patriotic imperative to produce homespun goods and promoted thrifty lifestyle changes to compensate for their growing shortages. Necessity as much as patriotic fervor compelled women to bring down spinning wheels from storage in order to spin and weave clothing for themselves, their families, and the soldiers in the field.

For the elite class of southern women, this created a social and identity crisis, since the task of weaving and spinning were typically relegated to the enslaved or were associated with poorer women who had neither the means nor convenience of purchasing thier clothes. Some soldiers, once they heard that their women were taking up the task, were outraged. Will Neblett told his wife, “I do not like the idea of your weaving. It is mortifying to me.”[10] Other soldiers, as Dr. James Broomall covered so well in his book, Private Confederacies, appreciated receiving clothing made by their loved ones, as it forged a connection with the home and family they left behind, and forged their identities as gentlemen soldiers.[11] Thomas Ruffin Jr. wrote , “[The men begged] that we shall try to get the materials, & have the clothing made at home: &… they say that they can fight better in clothes made at home.”[12]

In reality, the homespun movement hit numerous roadblocks. Those women who wished to take up the textile-making craft, but had never done so prior to the war, often lacked the instruction and the tools necessary to do so. One unexpected shortage was in cotton cards, which were used to comb the fibers before spinning it into thread. Until the war, cotton cards had been produced outside the South, and the supply of cotton cards already within the southern market began to dwindle as the war progressed. In the end, poor white and enslaved women who were already engaged in textile-making carried on with their production or increased their output, while women unfamiliar with the practice did not make a monumental impact in meeting the demand for textiles in the Confederacy. These women turned to purchasing more expensive goods that were run through the blockade, recycled old linens, or rehabilitated discarded garments to meet their needs.[13]

Instead of upping their homespun game, women took on knitting and sewing as their way of showing support for the soldiers in the field. Mary Gray remembered, “Many of us who had never learned to sew became expert handlers of the needle, and vied with each other in producing well-made garments; and I became a veritable knitting machine.”[14] Others found the task more difficult, but let their enthusiasm override their usefulness and sent deformed garments to the soldiers anyway.

So, while homespun didn’t take off as it did during the Revolutionary War era – nor did it save the South from economic ruin – southern women took pride in their ingenuity, and the concept of homespun became fixed in the iconography of the Confederate war effort. When looking at the big picture of social, political, and economic shifts for the South during the war, women’s new responsibilities as caretakers of their homes and plantations without the assistance of men created a far more lasting impact than any level of undertaking in domestic manufacturing. Still, the comparison of national endeavors in self-sufficiency between the American Revolution and the Civil War are uncanny, in rhetoric if not in practice.

For your listening enjoyment, here is Bobby Horton’s rendition of “The Homespun Dress” that inspired this article:

Endnotes

[1] “The Homespun Dress,” in Folklore of Mississippi and their Background, by Arthur Palmer Hudson, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1936, pp. 265-266 (can be accessed: https://www.civilwarpoetry.org/confederate/songs/homespun.html )

[2] Worthington C. Ford, ed. Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Washington, US Government Printing Office, 1904, reprinted 1968, p. 75-80

[3] Lawrence A. Peskin, Manufacturing Revolution: The Intellectual Origins of Early American Industry, Baltimore and London, John Hopkins University Press, 2003, p. 37

[4] Adam Anderson, An Historical and Chronological Deduction of the Origins of Commerce…, London, 1764 – reprint New York, A.. Kelley, 1967, p. xv

[5] “Philo-Americanus,” New York Journal, August 16, 1770, p. 2

[6] Drew Gilpin Faust, Mothers of Invention, Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1996, p. 45

[7] Southern Illustrated News, December 20, 1862.

[8] Milledgeville Confederate Union, January 13, 1863

[9] Peskin, p. 179

[10] Will Neblett to Lizzie Neblett, June 17, 1864, Lizzie Neblett Papers, Center of American History, University of Texas, Austin, Texas.

[11] James J. Broomall, Private Confederacies, The Emotional Worlds of Southern Men as Citizens and Soldiers, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2019, p. 36

[12] Thomas Ruffin Jr. to Thomas Ruffin, May 26, 1862, Box 30, Folder 450, Ruffin Papers, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

[13] Faust, pp. 48-49

[14] Mary Ann Harris Gay, Life in Dixie During the War, Atlanta, Constitution Job Office, 1862, p. 42

Bobby Horton is one of the most gracious gentlemen I’ve ever had the privilege to interview in this business.

It is estimated (depending on source used) that over 8000 patriotic songs were written, and published as sheet music during the Civil War (grand total of both sides.) It would be impossible to number the poems written: they were published by Walt Whitman; published in local newspapers almost daily (reader contributions); and penned by soldiers in their letters. Perhaps the most famous non-Whitman poem, Bivouac of the Dead, was penned by Southern soldier and veteran of Shiloh, Theodore O’Hara. It graces the entry to many National Cemeteries across the United States.

In regard to homespun versus machine-made clothing, the North had a near monopoly on sewing machines prior to the firing on Fort Sumter; and the machines were not sent south after April 1861. Great Britain also produced sewing machines, but they were usually not included as cargo of blockade runners. The masterful Quartermaster-General of the Union Army, Montgomery Meigs, prioritized necessities – bullets, guns, power and tents – and then contracted for mass-produced battle flags, shoes and uniforms, beginning mid-1862. A recent study concluded that over 80 percent of Federal uniforms examined in museums contained stitching by sewing machines; less than ten percent of Southern uniforms included machine-made stitches. Homespun was a necessity in the South.

Thanks to Sheritta Bitikofer for this interesting article.

As a simple patriotic song encouraging sacrifice, for the greater good it is a wonderful, sweet song.

Tom