A Taste of Vicksburg – The Story of the Jam Jar

Tucked away in the collection’s storage at the University of West Florida’s Historic Trust is a simple artifact with a greater history than meets the eye. A brown stoneware jar, about

eight inches tall and four inches in diameter, its exterior polished with a raised band around the middle. The story of the jar is told on a scrap piece of paper, reading,

Private Frederick Beaver of the Wisconsin Volunteers found this jar when full of jam in a farm house just outside Vicksburg Miss. during the battle of Vicksburg. He carried it home and it remained in the family until December 1959

For a jar that traveled hundreds of miles to end up in Pensacola after nearly 160 years, it’s in great shape. The jar becomes more interesting, considering that it was commonly recommended that jam was stored in clear glass jars, not stoneware, so as to show any potential mold growing inside.[1] It’s more probable that this jar would have been used for pickling, which the tag (in picture) refers to as such, though other accounts state it was filled with jam instead. Secondly, in order for this jar to be full of jam, the cook would have had to use at least 4-5 pounds, if not more, of berries that were abundant in the Vicksburg area. This estimate is based on a raspberry jam recipe found in an 1879 cookbook that collected a multitude of recipes from American housewives across the country.[2] Seeing as this cookbook was endorsed by Mary Ellen McClellan – wife of former Union General George B. McClellan – and Rebecca Gordon – wife of former Confederate General John B. Gordon – I thought I’d give it a shot and immerse myself in the history behind the jar.

First, I searched for the most common berry found in Mississippi. Evidently there’s a lucrative industry in blueberries, which are easily purchased from the store in one-pound containers. Second, I searched for the easiest way to make blueberry jam that resembled the raspberry jam recipe found in the book, just to make sure I wasn’t about to make jam the historical way and give myself food poisoning in the process. Luckily, the recipe in the book mirrors that of a modern, no-pectin recipe for blueberry jam.

Start off with your chosen poundage of blueberries in a cooking pot with a little bit of water. Not a lot, just enough so the berries don’t burn on the bottom of the pot. Lightly mashing most of the berries to add juice to the mix, bring the concoction to a boil. Add one half a pound of sugar for each pound of berries. If it’s easier and you don’t own a kitchen scale, interchange with “cups.” A pound of berries comes out to two cups, therefore add one cup of sugar. It works out the same.

Stir in the sugar, lower the heat, and continually stir until the jam begins to thicken. This could take upwards of 20 minutes – it could be longer, depending on your batch size. Here’s a neat test to make sure your jam is ready: put a small plate in the freezer for about 5 minutes. Once it’s pretty cold, take it and dollop out a small bit of the jam. Let it cool and solidify for a moment, then nudge it (with a finger or a spoon). If the surface wrinkles, it’s ready!

Heat your glass jars with very hot water – either immerse them or pour in boiling water from a kettle. This is to prevent any cracking of the glass when you dish in the very hot jam. Use gloves or a dish rag to avoid burns. Two cups of uncooked berries produces about a half a pint of finished jam. For modern preservation purposes, one can still pressure-seal the jars either with a machine or through the boiling water technique.

For extra authenticity, I tried my hand at baking, which is usually not a good idea. A recipe from 1857, found in Mrs. Hale’s New Cook Book, provided a relatively simple recipe that I still managed to get wrong.[3] Though the bread itself was pretty salty and it was impossible to slice, the added spread of blueberry jam improved it.

I tried to imagine what it would have been like for a Federal soldier to stumble across a jar full of this jam. How excited he must have been for something sweet to supplement his rations during the summer siege of Vicksburg. More precisely, I wanted to know the soldier who found it and brought it home as a souvenir of war.

Frederick Beaver was born on December 18, 1833 to Joshua Christian and Catherine Havice Beaver in Mifflin, Pennsylvania. He was one of 10 – potentially 13 – children. His family moved to Wisconsin and Frederick married Promelia Swanger in 1857. By 1860, he lived in Sauk, Wisconsin as a farmer with a real estate value of $300. They had two children before war broke out, young Sarah (age 2) and Robert (5 months). A third child, named after his father, was born in October of 1862, just two months after Frederick enlisted in the Union army.[4] By now, three of his brothers had already enlisted, Peter (36th Wisconsin, Company A), Thomas (2nd Wisconsin, Company H), Sampson (a gun corporal with the 6th Wisconsin Light Artillery), and Henry (23rd Wisconsin, Company G). Frederick and his brother, John, enlisted with Henry’s regiment, but were members of Company K. Shortly after the three Beavers enlisted in the 23rd Wisconsin, Thomas died on September 18 after he was wounded and captured at the Battle of Gainesville – also called Brawner’s Farm – which took place in August.[5]

The 23rd Wisconsin Infantry mustered under Colonel Joshua J. Guppey, previously of the 10th Wisconsin, and moved south to join the 13th Army Corps with General William T. Sherman in preparation for the Vicksburg Campaign. That December of 1862, the Wisconsin troops embarked from Milliken’s Bend where they had encamped, to the interior of Louisiana, destroying railroads and enemy communications. They also fought at the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou where Sherman failed to advance upon Vicksburg from the north. In January of 1863, Frederick and his brothers fought in the battle at Arkansas Post. Both Companies G and K led an advance that succeeded in capturing several blockhouses and occupied the Confederate forces, pushing them back into their works while the rest of the regiment attacked and carried the enemy rifle pits. The battle raged for three hours before Confederate Brigadier General Thomas Churchill surrendered. The 23rd Wisconsin sustained a loss of 6 killed and 31 wounded. Among the wounded was Frederick, though the nature of his wound is unknown. By family oral history and his military career, it can be suggested that this wound gave him trouble later in life.

The regiment engaged in some minor expeditions between February and March before following the 13th Corps south to Grand Gulf in General Ulysses S. Grant’s plan to attack Vicksburg from the rear. They crossed the Mississippi River on April 30 and served as reserves during the battle at Port Gibson on May 1. They took the advance of their division and supported the 17th Ohio Battery during an artillery bombardment at Champion Hill near the Coker House on May 16. His regiment charged an open field under heavy fire, taking shelter in a low rise before a road that ran parallel to the Confederate position. They held this dangerous position until the enemy retreated.

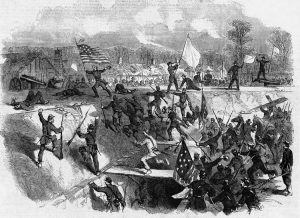

Outside Vicksburg, the 23rd Wisconsin was with Brigadier General Stephen G. Burbridge’s brigade on the south side of the battlefield, facing Brigadier General Stephen D. Lee’s brigade of Alabamians. They participated in the May 22 assault, but was unable to scale the walls of their fortifications. The regiment hunkered down into siege duty until the surrender of John C. Pemberton on July 4, 1863. The Confederate carrying the white flag of truce on their portion of the line was halted by Captain Ephraim Fletcher of Company K, Frederick’s company. It was at some point between May and July of 1863 that Frederick found the jar of jam.

The regiment went on to participate in the Red River Campaign in Louisiana, though Frederick transferred to the Veteran Reserve Corps on April 6, 1864, the same day that the regiment marched out from Natchitoches, Louisiana, and two days before the Battle at Sabine Crossroads. Frederick would also miss out on fighting in one of the last major battles of the war, which took place at Blakeley, Alabama opposite Mobile on Mobile Bay. The 23rd Wisconsin mustered out in Mobile on July 4, 1865. Out of their original strength of 994, the regiment suffered 289 killed during the war.[6]

In 1870, Frederick and his family moved to Brookfield, Iowa where they had four more children (Jene, Robert, Lewis, and Abigail), and continued work as a farmer.[7] On the 1880 census, the Beaver family was now in Danville, Iowa, with four more children listed (Erwin, Joal, Wallace, and Laura) making a total of 11 children.[8] Frederick died on June 28, 1894, in Danville. His name was crossed off the Iowa State Census of 1895, though his wife and a few children were listed.[9]

The jam jar from his war days was passed down through the family until it came to a descendent in Pensacola, Florida. It was then donated to the T.T. Wentworth Museum (now Pensacola History Museum) where it is housed in their collections today. Through these artifacts of the war, we can learn more about not just the individuals who may have possessed them, but the role the objects played in the culture of the time. While the jar isn’t ideal for storing jam, one can imagine that it was used and reused for multiple purposes by the Beaver family after it was toted off the battlefield at Vicksburg. It might have sat on a shelf for decades, a subtle reminder of those couple of months spent in the Mississippi heat where armies lay siege to the port city of Vicksburg.

Endnotes

[1] Marion Cabell Tyree, ed. Housekeeping in Old Virginia, Louisville, John P. Morton and Company, 1879 p. 444

[2] Ibid, p. 452

[3] Sarah Josepha Hale, Mrs. Hale’s New Cook Book, Philadelphia, T.B. Peterson, 1857, p. 428 (online explanation of recipe: https://www.worldturndupsidedown.com/2011/09/civil-war-bread-recipe.html)

[4] 1860 U.S. census, population schedule. NARA microfilm publication M653, 1,438 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records

[5] Wisconsin. Adjutant-General’s Office. Roster of Wisconsin volunteers, War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865, Volume II (Madison, 1886), p. 253 (Frederick and John).; Ibid, p. 246 (Henry); Ibid, p. 579 (Peter); Volume 1, p. 223 (Sampson); Ibid, p. 368 (Thomas) – Online facsimile at http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/u?/tp,35928

[6]E.D. Quiner, Military History of Wisconsin, chapter 31: 23rd Infantry, 1866, Clarke & Co, pp. 707-719, Online access: https://content.wisconsinhistory.org/digital/collection/quiner/id/16611 )

[7] 1870 U.S. census, population schedules. NARA microfilm publication M593, 1,761 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Record

[8] 1880 U.S. Census, population schedule. Record Group 29NARA microfilm publication Roll T9, 1454 rolls. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[9] Iowa, U.S., State Census Collection, 1836-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Danville, Iowa, 1895 – Microfilm of Iowa State Censuses, 1856, 1885, 1895, 1905, 1915, 1925 as well various special censuses from 1836-1897 obtained from the State Historical Society of Iowa [access: http://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?db=iastatecen&h=5201591&ti=0&indiv=try&gss=pt ]; Find A Grave. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi: accessed 18 January 2013.

Always glad to see Vicksburg get a little love!

Great story! The research must have been filling!

I like how the author frames this: PVT Beaver “found the jar … in a farm house.” That is funny. I think he author means he *stole* it from a farm house near Vicksburg. I could post a couple of links here to stories about the plundering Federals near Vicksburg.

Tom

Those weren’t my words, but the words from the note that accompanied the jar in the historic trust’s collection. The note was written by the donor perhaps sixty years ago, whom I presume learned about its history through family oral traditions. I make no assumptions whether it was stolen or perhaps found in an abandoned farmhouse near the battlefield. That wasn’t my focus while writing this, and others can tackle that topic.

Reminds me of when picked blueberries in Mississippi as a kid.