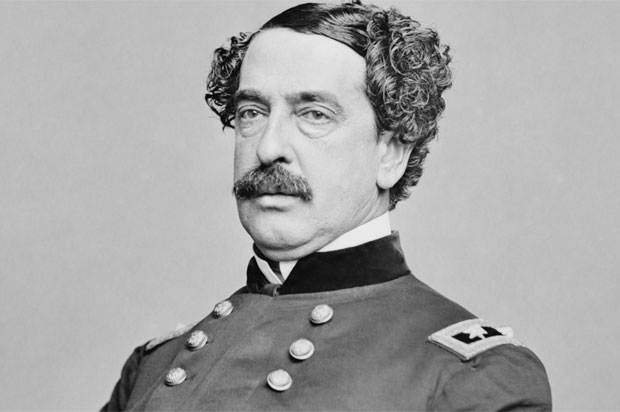

What if John Reynolds had not been killed at Gettysburg?

John Reynolds’s unexpected death on July 1, 1863, in the opening hours of America’s most famous battle, has elevated him to near-mythic stature. His fans are tantalized by the possibilities his survival might have offered (no less so than Stonewall Jackson fans who are likewise tantalized by What Ifs). I’m not a Reynolds fanboy, per se, but asking about his possible survival does provide us with an excellent opportunity to better understand what was supposed to happen on July 1, 1863. Would it have happened that way had Reynolds lived?

Reynolds death is a real-life illustration of what counterfactual historians call “the magic bullet.” It’s an unforeseen accident that changes the course of events in unforeseen ways. Perhaps the most famous example comes in MacKinlay Kantor’s If the South had Won the Civil War. A horseback riding accident kills Grant after the May 12, 1863, battle of Raymond, Mississippi, leading to Maj. Gen. John McClernand’s promotion to command, which takes a disastrous turn. No fall of Vicksburg; no rise of Grant; no Union war victory.

Such conceits are fun for the fiction writer because they open up any imaginable possible outcome. But such “Act of God” events have become a worn-out trope—Greek dramatists commonly used them, and so did Shakespeare, and they’ve been employed for convenience ever since. They are a storyteller’s most contrived tool to advance or resolve stories. In fact, they’re too convenient, and for historians, not useful at all because by their very nature, they aren’t intended to illuminate anything. They are just designed to force a plot in a certain direction, usually toward resolution.

Reynold’s death illustrates this in a real-world situation.

When George Gordon Meade took over command of the Army of the Potomac on June 28, he sent Reynolds forward at the head of a reconnaissance in force in an attempt to ascertain the Army of Northern Virginia’s exact location and intentions. Reynolds commanded the left wing of the army: his I Corps along with Oliver Otis Howard’s XI Corps and Dan Sickle’s III Corps.

The I Corps led the way, with Reynolds at its head. Howard’s XI Corps followed in support but was not originally intended to enter the fray; Reynolds ordered it to come within supporting distance, about two and a half miles south of Gettysburg (just north of what is today the Peach Orchard). Meanwhile, Sickles’s III Corps was to hang back in Emmitsburg, Maryland, to protect the left flank of the entire army and provide support as Reynolds fell back.

Based on intelligence reports, Meade ordered Reynolds to “advance on Gettysburg,” but the commander did not see the town as a spot for defense.[1] Gettysburg “would not at first glance seem to be a proper strategic point of concentration for this army.”[2] Rather, if Confederates advanced on Reynolds, “you must fall back” to Emmitsburg, where Sickles could reinforce him.[3]

In short, Meade’s intention was for Reynolds to get Lee to show his hand and then, having ascertained the Confederates’ location and intent, fall back, drawing Lee after him toward a defensive position Meade was staking out about fourteen miles to the rear.[4] As Reynolds fell back, he’d meet up with Howard’s force and, later, Sickles’s, on the withdrawal, bolstering his forces even as Lee chipped at them.

Meade had been eyeing a position that eventually became known as the Pipe Creek line. The position roughly followed a ridgeline that parallel Big Pipe Creek, with Manchester, Maryland, on the east end and Middleburg, Maryland, on the west. “A battle-field is being selected to the rear, on which the army can be rapidly concentrated . . .” Meade wrote to Washington.[5]

Even as Reynolds was fatally shot on the battlefield at 10:30 a.m., July 1, Meade was drafting a circular that outlined his defensive position and his intentions to draw Lee to Pipe Creek. Meade finished his plans around noon with the help of his adjutant, Seth Williams, and directed Chief of Staff Daniel Butterfield to distribute copies.

The general plan was consistent with what Meade had earlier discussed with Reynolds with one key difference. Meade had originally told Reynolds to withdraw toward Emmitsburg and the support of Sickles’s III Corps. The new position would instead require Reynolds to withdraw down the Taneytown Road, a little to the east.

Worried Reynolds would not get the message in time, Meade sent II Corps commander Winfield Scott Hancock forward to confer with Reynolds and redirect the withdrawal. Hancock’s corps would follow, advancing up the Taneytown Road to provide additional back-up for Reynolds as Reynolds withdrew toward the new Pipe Creek line. The II Corps would serve in much the same capacity as Sickles’s III Corps was to have originally served had Reynolds withdrawn toward Emmitsburg.

Just before Hancock set out, word finally arrived of Reynolds’s death. Meade again met with Hancock, who was instructed “to give the necessary directions upon my arrival at the front for the movement of the troops and trains to the rear toward the line of battle [Meade] had selected, should I deem it expedient to do so.” Otherwise, “establish the line at Gettysburg” if that proved more prudent under the changing, uncertain circumstances.[6]

It took nearly two hours to get from Meade’s headquarters to the front. By the time Hancock arrived on the battlefield, a universe of fighting had occurred. Hancock had the sharp situational awareness to realize the army was in for a penny, in for a pound by then.

Perhaps more than anything else, the gravel-growl of Sam Elliott as John Buford praising the “good ground” has made it accepted wisdom that the battle was destined to unfold around the small college town. Much has been made of Buford’s harried-but-heroic fall-back defense along the Chambersburg Pike on the northeast side of Gettysburg. That defense allowed Reynolds to get to the field and throw his infantry in. Forgotten in the scenario, though, is Meade’s direction to Reynolds to develop the situation and fall back.

Reynolds only had one of this three divisions—James Wadsworth’s—with him when he arrived on the field. At Buford’s urging, Reynolds directed them in as relief for Buford’s bedraggled troopers. He called up his other two divisions, as well, but a courier to Howard directed only that the XI Corps position itself near the Wentz house and the Sherfy Peach Orchard.[7] It’s hard to know what Reynolds actually intended at this point, but his actions suggest that he was going to deploy his divisions enough to credibly tangle with Confederates while still maintaining Howard in a position that would support an eventual withdrawal. He likewise knew that any other support was ten miles away and farther; relief would take hours of marching to arrive. In fact, the next force likely to arrive on the field were more Confederates as Buford’s troopers brought word of the approach of Richard Ewell’s Second Corps from the north.

Reynolds’s reconnaissance in force did exactly what Meade had intended: it flushed out the location of Lee’s army and forced it to show its intentions. “The news proves my advance has answered its purpose,” Meade wrote to Washington as he parsed through initial dispatches.[8]

It makes little sense to think Reynolds wanted to pick a fight with an unknown number of Confederates with little available help. As he directed Wadsworth’s division into the fight, he still had ample opportunity to carry out Meade’s plan.

Then of course came the bullet that killed him, and his successor, Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday doubled-down, ignoring the left wing’s role as a reconnaissance in force. Doubleday found out about Reynolds’s death at about 10:45—about 15 minutes after it happened—and as the senior division commander, he ascended to corps command. “The whole burden of the battle was thus suddenly thrown upon me,” he later said.[9]

Doubleday well knew the plan: Reynolds had briefed him on it that morning at a 7:00 meeting. “It was General Reynolds’ intention to dispute the enemy’s advance at this point, falling back, however, in case of a serious attack, to the ground already chosen at Emmitsburg,” Doubleday later admitted.[10]

But in the moment, Doubleday told an aide, “all he could do was fight until he got sufficient information to form his own plans.”[11] Events unfolded at whiplash speed, though, and Doubleday barely had time to react, let alone plan. “The whole of these events had occurred on the right so soon after my arrival, that there was no opportunity for me to interpose, issue orders, or regulate the retreat,” he said.[12]

Doubleday conceded that an opportunity to withdraw did present itself. “[I]t might seem, in view of the fact that we were finally forced to retreat, that this would have been a proper time to retire,” he wrote; “but to fall back without orders from the commanding general would have inflicted lasting disgrace upon the corps, and as General Reynolds, who was high in the confidence of General Meade, had formed his lines to resist the entrance of the enemy into Gettysburg, I naturally supposed that it was the intention to defend the place.”[13]

This defense rings hollow because, in fact, Meade had already intended for the I Corps to fall back. That was the entire plan. Whether Reynolds was executing that plan or not at the time of his death remains a source of controversy, but Doubleday did have the opportunity to execute it himself but chose not to.

Doubleday did a credible job directing the I Corps on the rest of that July 1, but Meade held a grudge against him that dated all the way back to Doubleday’s failure to support Meade during Meade’s breakthrough at the battle of Fredericksburg. Meade may have also been frustrated that Doubleday had, however inadvertently, foiled Meade’s Pipe Creek plan by further entangling the army rather than disentangling it and falling back. As a topper, Howard through Doubleday under the bus when Hancock arrived on the field, blaming the I Corps commander for the collapse of Union lines north and west of town. Such factors contributed to Meade’s decision to replace Doubleday at the head of the I Corps with the less-senior John Newton.

By the time Hancock showed up on the field, the prospects of disentanglement seemed impossible. The fallback position Howard had staked out on Cemetery Hill looked promising as an alternative. Hancock is often praised for his endorsement of that position as good grounds for fight, and he should be (and Howard deserves credit for picking it in the first place), but the situation on the ground that Hancock rode into would not have been anything John Reynolds would have had in mind had Reynolds lived. Reynolds didn’t know about Cemetery Hill, although, had he received and followed his revised orders to fall back down the Taneytown Road, he would have marched right along the west face of it in his move southward.

Had Reynolds lived, would he have thrown his divisions in to escalate the fight, or would he have engaged them just enough to entice Lee to come on harder and then lure Lee onward toward Pipe Creek? That’s the crux of the moment, and we’ll never know, even though we know what Meade wanted him to do.

Thus, Reynolds’s death perfectly demonstrates the magic bullet theory of alternate history: an unexpected death changes the flow of events in unexpected ways. Instead of a reconnaissance in force—a skirmish and a withdrawal—we ended up with the largest land battle ever fought on the North American continent. A fiction writer could not have penned a magic bullet with more impact.

————

For more discussion of What Ifs, join us for the Eighth Annual Emerging Civil War Symposium at Stevenson Ridge, August 5-7, 2022, in Spotsylvania Court House, Virginia. Our theme this year is “Great What Ifs of the American Civil War.” Tickets are still available. Click here for more details or to reserve your spot!

————

[1] Meade to Reynolds, 30 June 1863, O.R. XXVII, Pt. 3, 420.

[2] Williams to Reynolds, 1 July 1863, O.R. XXVII, Pt. 3, 460.

[3] Meade to Reynolds, O.R. XXVII, Pt. III, 420.

[4] For more on this, see Kent Masterson Brown, Meade at Gettysburg: A Study in Command (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2021), 101-5.

[5] Meade to Halleck, O.R. XXVII, Pt. 1, 70-71.

[6] Hancock report, O.R. XXVII, Pt. 1, 367.

[7] Oliver Otis Howard, Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard (New York: Baker and Taylor, 1908), 409.

[8] Meade to Halleck, O.R. XXVII, Pt. 1, 70.

[9] Doubleday report, O.R. XXVII, Pt. 1, 245.

[10] Doubleday report, O.R. XXVII, Pt. 1, 244.

[11] Quoted in Brown, 133.

[12] Doubleday report, O.R. XXVII, Pt. 1, 246.

[13] Doubleday report, O.R. XXVII, Pt. 1, 246.

This a rather concise and masterful explanation of the Union’s initial plan regarding the advance to Gettysburg and the falling back to the Emmittsburg line.

I would have to disagree regarding the comment..”Reynolds didn’t know about Cemetery Hill”. We have no idea if Reynolds did or didn’t know about Cemetery Hill. We do know that he stopped at the George George House ( Gettysburg The First Day, Pfanz, p. 73), and may have observed it then.

We have no idea what Buford and Reynolds had discussed.

What we do have though, is an oral message that Reynolds sent to Meade. Captain Stephen Weld was the messenger , and Pfanz says the message was sent at 10:00 A.M.(p.74). “He reported that the enemy was approaching Gettysburg in force and that Reynolds feared that the Confederates would seize the heights on the “other side” (south or east) of the town. Nevertheless, he would would fight them all through the town and keep them back as long as possible”.(Pfanz, p.74)

Fighting through the town and holding them back, can only mean Cemetery Hill.

Now, we all know the importance of high ground in the Civil War. And if the Confederates had occupied Cemetery Hill, the AoP would have had to attack and may have suffered tremendous casualties in that attack. A foreign invading army on American soil has to be attacked. Recall the Maryland Campaign and McClellan’s pursuit and attack.

We all know that Hooker , at Chancellorsville, stole a march on Lee and was on the flank of the ANV. Hooker intended that Lee and the ANV retreat.

My question: What did Meade see in the 2 intervening months that would make him now think that Lee would do want Meade intended Lee to do?

I think it all comes back to the advantages of high ground with the Union forced into a “mule shoe” that goes from Powers Hill, Culp’s Hill, Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge and Little Round Top.

I agree, the Weld comment suggests Reynolds had determined to fight in Gettysburg–except at that point, Meade’s orders are clearly to fall back to Maryland. It is possible that Reynolds had, by then, received Meade’s orders to fall back along the Tanyetown Road rather than toward Emmitsburg, in which case he definitely would have had the heights to the south and west of town in mind because he’d have had to fall back that way. (Hancock was sent up there in person in case Reynolds had not received those orders, but to my knowledge, we don’t know if Reynolds got them or not. It’s possible he had.)

We have the benefit of hindsight, so it’s easy to piece together sketchy evidence to create the end picture we know we need to have. I’m suggesting that there’s maybe some extra room in there to consider some things simply because the evidentiary trail does have some gaps.

The wonderful Latin term for the magic bullet is “deus ex machina” or “god from the machine” referring to the practice in ancient Greek tragedy of lowering a god onto the stage from a crane or elevating him through a trap door to suddenly and unexpectedly resolve or redirect a plot line. Today the term suggests an artificial and therefore unsatisfying ending implying a lack of creativity on the part of the author.

Thoughtful article, Chris. I think we have a good idea of what Reynolds would have done had he lived, per the reference to Captain Stephen Weld by the ubiquitous nygiant1952 in his comment. To which Meade’s biographer, Freeman Cleaves, claimed Meade responded, “Good! That is just like Reynolds, he will hold on to the bitter end.” [p. 135]

I’m not entirely convinced that Reynolds would have gone all-in. I’m not saying he wouldn’t, and it certainly looks like he was in the process of doing so. But I do think he was a smart-enough soldier to think twice about committing his corps piece-meal into a fight against a foe of unknown size knowing the rest of his own support was spread far afield. In the context of his orders, it makes a lot more sense that he would’ve been setting up the fighting withdrawal Meade asked for.

I also think it makes Reynolds’s death more heroic if we think of it in the context of meeting the enemy head-on, throwing himself into the fight. People love a hero.

If this post does not whet the appetites of those already registered for the conference and those still considering attending, it is hard to know what might.

One small nit: the first line of the paragraph with the footnote #6 should read “Reynolds death” (not Hancock’s). Even the most enthusiastic and undisciplined what-ifer would be hard pressed to imagine a Union general arriving on the field to witness his own earlier death. (I know it’s a typo. New students might be confused.)

Thanks for the nit pick, Rosemary. Fix made!

Hi John,

if you mean by ubiquitous, constantly encountered…Thank you!!

I put some emphasis on that message for it is the only communication that has been left to us, of Reynolds’ decision making. And I believe you have to take the 2 sentences together.

I enjoy and welcome your comments, nygiant1952!

back at you John!

Hi Chris,

Certainly, the evidence that we have leaves some large gaps when we try and interpret the battle. Reynolds was killed with 45 minutes of issuing that communication to Capt. Weld, and Buford was dead by the end of the year.

One of the better accounts I have had is an article in the old Blue and Gray Magazine, John Buford at Gettysburg, By Gary Kross. It’s the February 1995 issue. It is usually available EBay.

I feel Buford recognized the importance of Cemetery Hill as key ground. If taken by the Confederates, the Union would have suffered casualties in trying to take it back.

I don’t buy that Lee woujd attack Meade along Pipe Creek. Too strong a position. A foreign Army on American soil HAS to be attacked. Thats what McClellan did in the Maryland Campaign.

Hindsight is 20/10 vision….the same eye acuity of Ted Williams.

I’ve never believed Lee would fall for the Pipe Creek strategy, either. That was wishful thinking on Meade’s part.

A factor to consider in Reynolds’ decision-making is that he was a native Pennsylvanian from nearby Lancaster. The Confederates were invading his home, his land. Even subconsciously, that could have steered him toward staying and fighting, particularly in a complex and dynamic situation.

I’m flummoxed that there’s no mention of Reynold’s message to Meade that he would barricade Gettysburg if necessary. To me its indicative of an intention to fight it out.

This is a great article. It explanations Meade’s plan, it covers how Doubleday got disrespected, and at least the friction between Doubleday and Meade, although I thought an earlier post regarding Meade stunted success at Fredericksburg laid the blame for Meade’s lack of support on Reynolds.

It’s also a great article because it showed another example of AOP leadership not understanding Lee, as they expected Lee to do what they wanted him to do. He was on his way to Harrisburg unfettered and they want to draw him back into Maryland. What’s his motivation for that?

Excellent post! Worthy of a panel at some future ECW event at Stevenson’s Ridge.

I have read and listened to numerous articles and documentaries that Sickles was a few miles north of Emmitsburg and Slocum was within 5 miles of Gettysburg at around 11 o’clock waiting to hear from Reynolds whether to come to his assistance or stay where they were and wait for him to fall back. After he was killed both continued to hold their positions while being asked by both Howard and Doubleday to come to their assistance. Howard’s original placing of his Corps seems to follow with Reynolds in that he was supposed to protect from the north and the I Corps was supposed to slowly fall back through the town onto Cemetery Hill pulling Hill and Ewells available troops into an engagement of their choosing with Slocum hitting Early’s open flank as we he would have been coming down from the north and then Sickles arriving a little later would have rolled up Hill’s men as night was falling. Barlow’s moving up to the knoll caused things to change and both Slocum and Sickles reluctance to move faster didn’t help. had Barlow stayed where was placed, the guns from Cemetary Hill could have covered him held off Early long enough for the I Corps to orderly fall back first while Schurz’ division be the rear guard through town and bottle up the Confederates for longer.