“Blackest Man in New Orleans” – Captain Cailloux of the Louisiana Native Guards – Part 1

The unit that would be later known as the Louisiana Native Guards found its start, astoundingly, in Confederate Louisiana in May of 1861. Accepted as a militia regiment by Governor Thomas Moore, 33 black officers and 731 privates – all free men of color with some European ancestry – the black regiment was intended to assuage Northern propaganda that claimed the Confederacy was racist and fighting for the preservation of slavery.[1] It was written in the Daily Crescent of New Orleans that the black regiment “will fight the Black Republican with as much determination and gallantry as any body of white men in the service of the Confederate States.”[2] However, the Confederacy never intended to arm these “hommes de couleur libre” as they were called, and the unit only participated in two dress parades, one in November of 1861 and the second in January of 1862. The militia unit was disbanded on February 15, 1862 but was momentarily reinstated when New Orleans panicked at the arrival of Union Flag Officer David Farragut and his flotilla.[3] They were ordered to guard the east end of the French Quarter until Farragut’s imminent arrival prompted the evacuation of the city and its black militia.[4] Farragut arrived to the Crescent City in April after running the gauntlet past Fort Jackson and Fort St. Phillips along the Mississippi River, and New Orleans surrendered to the Union Army in early May.

Louisiana would not enlist the military support of its black citizens again until under Union occupation, when Major General Benjamin Butler was approached by former officers of the Confederate Native Guard who asked for the chance to serve the Union army. Butler had previously turned down suggestions from Brigadier General John W. Phelps when he made the point that the army could use free men of color and black “contraband” who escaped slavery behind Union lines. Fearful of repercussions from Washington, he had initially refused the idea of arming the formerly enslaved. However, true to Butler fashion, he changed his mind and flipped the situation so as to give glory to himself for the idea. He wrote, “I shall call on Africa to intervene” in his want of reinforcements to defend his Department of the Gulf. “I have determined,” he wrote to Washington, “to use the services of free colored men who were organized by the rebels into the Colored Brigade, of which we have heard so much… and they will be loyal.”[5] Therefore, on September 27, 1862, the 1st Regiment of the Louisiana Native Guard was mustered into service for three years, one of the first black regiments sanctioned in the Union army. Only 11 percent (108 men) of the regiment had previously served in the Confederate militia group, with over half consisting of formerly enslaved blacks from the plantations surrounding New Orleans.[6]

The captain who organized and recruited Company E of the 1st Regiment of Louisiana Native Guards was André – sometimes spelled Andrew – Cailloux (pronounced Cah-you). Many of the free people of color in New Orleans were noted for their lighter complexion, indicative of European influences in their lineage. In some instances, their lighter skin was the ticket to leniency in social mobility and comprised a class all their own. Cailloux appears to be an exception to this trend, as he took special pride in being the “blackest man in New Orleans” and enjoyed some special privileges in the free black community. He was born into slavery in 1825 on the plantation of Joseph Duvernay near Pointe a la Hache in Plaquemines Parish. He purchased his freedom at the age of 21 and soon after, in 1847, Cailloux married Félicie Coulon. A year after their marriage, Cailloux had earned enough money to purchase his mother out of bondage. Cailloux and Coulon had four children born free, three of whom survived to adulthood. In 1852, Cailloux bought a piece of property for $200 at Prieur and Perdido streets, then a few years later bought a Creole cottage uptown on Baronne Street for $400. He became a cigar maker, establishing his own shop in the Faubourg Marigny, and was known as an accomplished horseman, boxer, and athlete. Felicie Cailloux also earned a place for herself in the community as the first principal at the Couvent School. The school was formally known as the Institute Catholique – or the Catholic School for Indigent Orphans – located in the Faubourg Marigny and taught children of free people of color for a modest tuition.[7]

In New Orleans, skin color was firmly linked with one’s status as free or enslaved, meaning that the lighter skin one had, the greater social advantages they could be afforded. It may also be insinuated that a free black with lighter skin could have been manumitted by their white relatives – potentially their biological father who also enslaved them – or was born free and therefore did not earn their freedom by any sort of merit or hard work. Cailloux was a man who was considered free but took pride in having much darker skin than other free blacks and was first born into slavery before working his way out of bondage. He was in a unique position to bridge the gap between the black social classes. He epitomized the sort of virtues and ideal role model for newly freed blacks, while also proving to the rest of the free black community that he was no less of a man for his skin color. André’s enlistment as a captain, a rank that black soldiers in the Union army were often barred from achieving, also meant a great deal to the cause of equality. His conduct as an officer and a soldier – as well as the conduct of all the other black officers of the Louisiana Native Guards – would either condemn or validate the worthiness of blacks to hold such a rank.

The subsequent 2nd and 3rd Regiments were mustered into service that following October and November, consisting almost entirely of formerly enslaved men of Louisiana, though Butler still hadn’t received official permission to recruit blacks into the Union army. That wouldn’t come until the newly appointed general-in-chief of the Union army, Henry Halleck, granted passive consent in late November of 1862.[8]

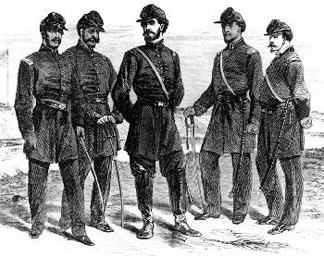

For the three Native Guard regiments stationed at Camp Strong outside of New Orleans, earning respect as Union soldiers was difficult, if not impossible. Under black officers, privates were drilled and engaged in fatigue duty – menial labor and engineering tasks. Many commended them for their discipline and eagerness to learn, though some attributed their quickness and obedience to orders to the fact that they were black, saying, “he [the black man], on his part, has always been accustomed to be commanded.” Though Butler never intended for them to see combat, many remarked on their belief that the men of the black regiments would “fight to the death” if given the chance.[9] White soldiers and civilians were not enthusiastic about the Native Guards. Prejudice against blacks, whether in uniform or out of uniform, could be found throughout the Union army. The consistent arguments from the doubters were summed up by the Daily Picayune in the summer of 1862: “The unfitness of the negro for military service is known to everybody… his life of slavery and subjugation would render the adult slave a very unsafe person to be entrusted with a musket against the man whom he has all his life looked up to as his master and superior.”[10] For others, they needed little convincing to reverse previous prejudices, such as Captain James Fitts of the 114th New York who wrote, “as I looked down the ‘long, dusky line’ and saw the soldierly bearing of these men, their proficiency in the manual of arms, and the zeal which every unit of the mass displayed in correctly performed his part of the pageant, the barriers of prejudice which had been built up in my mind began to fall before the force of the accomplished facts before me.”[11] Still, the Native Guards’ struggle for respect persisted throughout the war, facing racism in society and within the army on countless occasions.

Their chance to prove themselves under fire came in 1863. Though the new department commander, General Nathaniel Banks – who replaced Butler in December of 1862 – schemed for almost two years to replace black officers in the Native Guards with white ones, he facilitated their first test of valor and discipline in combat. While the 2nd Regiment served garrison duty on Ship Island off the coast of Mississippi, the 1st and 3rd Regiment were ordered to Baton Rouge in preparation for a march to Port Hudson, further north along the Mississippi River.[12] The citadel on the bluffs overlooking the river prevented the passage of Union ships from sailing to Vicksburg where General Ulysses S. Grant attempted his own campaign. The first assault on Port Hudson occurred on March 14, but the 1st and 3rd Regiment of the Native Guards would not join the army there until March 25 and an order for an all-out assault was issued by Banks for May 27. They were positioned on the right flank of the Union line, straddling the Telegraph Road and in front of Big Sandy Creek. Their commander, Brigadier General William Dwight, Jr. wrote that he considered the use of black troops at Port Hudson was intended to “test the negro question” and that “You may look for hard fighting, or for a complete run away.”[13]

For the Louisiana Native Guards, the stakes could not have been higher. Not only were they to face battle for the first time, it’s likely that they understood that how they behaved on the battlefield mattered for the millions of blacks across the country. It was a make or break moment, and Captain Cailloux rose to the challenge.

To Be Continued…

Endnotes

[1] United States. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Washington :[s.n.], 1894., Series 1, Volume XV, p. 556 (hereafter referred to as OR)

[2] New Orleans Daily Crescent, May 29, 1861

[3] Charles H. Wesley, “The Employment of Negroes as Soldiers in the Confederate Army,” (Journal of Negro History, Vol. IV, 1919), pp. 245-253; New Orleans Daily Picayune, November 24, 1861, January 8, 1862; Orders No. 426, March 24, 1862 in OR Series 1, Volume XV, p. 557

[4] “An Ex-Native Guard” to Chief Editor of L’Union, in New York Times, November 5, 1862; James G. Hollandsworth, Jr. The Louisiana Native Guards: The Black Military Experience During the Civil War, (Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 1995), p. 10

[5] Ibid, pp. 12-17; Butler to Stanton, August 14, 1862, OR, Series I, Volume XV, pp. 548-549

[6] Compiled Records Showing Service of Military Units in Volunteer Union Organizations, 73rd Infantry, USCT, M-594, roll 213, National Archives, Washington D.C.; Joseph T. Wilson, Black Phalanx: A History of the Negro Soldiers in the Wars of 1775, 1812, 1861-1865, (1888, reprint, New York, 1968), p. 195

[7] Hollandsworth, p. 27; Stephen J. Ochs, A Black Patriot and a White Priest: André Cailloux and Claude Paschal Maistre in Civil War New Orleans (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000), 9-66. CPT André Cailloux, Findagrave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/13787526/andre-cailloux; “André Cailloux, Businessman and Soldier Born,” African American Registry, https://aaregistry.org/story/andre-cailloux-civil-war-hero/; Matthew Hington, “How A Black Civil War Hero’s Funeral Paved The Way For Second Lines,” Very Local: Know Your NOLA, June 25, 2021, https://www.verylocal.com/second-line-funerals/2058/

[8] Hollandsworth, p. 21; Halleck to Butler, November 20, 1862, OR, Series I, Volume XV, p. 162

[9] Wilson, p. 526; Douglass Monthly, January 1863, p. 777

[10] “The Negro Enlistment Scheme,” New Orleans Daily Picayune, July 30, 1862.

[11] James Franklin Fitts, “The Negro in Blue,” (Galaxy, Vol. III, 1867), pp. 252-253

[12] Hollandsworth, p. 51

[13] William Dwight Jr. to his mother, May 26, 1863, in Dwight Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts

Nice article. Just one quibble. It seems doubtful the CSA had any particular plan regarding the Native Guards, whether some intention to “assuage” Northern accusations or otherwise. Those days through Summer and Fall of 1861, New Orleans was chaotic and the CSA not much better. Planning for the defense of N.O. at the CSA level was haphazard. The Native Guards – like many militia units – had existed in various forms throughout Louisiana history. Free African-Americans had served under the Spanish, the French and now the Anglo-Americans. New Orleans African-Americans had served in every major action in Louisiana, including the slave revolt of 1811. The white leaders of New Orleans likely were not sure how to employ the Native Guards.. But, I expect at least early on, many of the New Orleans white leaders simply viewed the coming Federal invasion similar to the British invasion of 1815. It was all hands on deck and a strong sense of urgency.

Tom

Hey Tom,

You are correct that Louisiana has a history of utilizing black civilians in militia units. Florida (my home state) does as well. However, I also provide evidence in this post (and part 2) that Confederate officials and the general public did not have confidence in the military capabilities of blacks because of their perceived inferiority. If they had doubt of their competency, then why would they create a black militia unit in the first place if not for show? Also, there is nearly half a century between Andrew Jackson’s defense of New Orleans when he used free black soldiers at Chalmette and the coming of the Civil War. In that time, racial prejudice that was somewhat mild under French and Spanish rule in Louisiana escalated quite a bit in the years following its admission into the Union due to the migration of white American planters to the region with their extreme ideologies of white superiority. Not to mention the numerous national events (Nat Turner’s Uprising, the Dred Scott Case, and John Brown’s Raid) that encouraged distrust and antagonistic feelings toward the enslaved and free black population. I don’t deny that the measure to form a black militia unit might have been to get “all hands on deck” but in light of Confederate sentiment to think blacks were incapable of military service, it appears more likely that the formation of the Native Guards was a political move than anything. Historian James Hollandsworth, who has written a book on the history of the Native Guards, shares this observation.

Thanks for the reply, Sheritta. I do not disagree with any of your comments. But, the Battle of New Orleans was a big deal in N.O. The day of the battle was observed every year with military parades and celebrations up through January, 1861. The 1815 veterans always marched in the parade. Too, I do not know if you are suggesting some person in authority created the Native Guards. But, if you are, I tend to think otherwise. The nature of militia units in ante-bellum Louisiana – as in other states before the CW – was they grew organically. Yes, I have read through most of Hollandsowrth’s book. I do not recall him suggesting the Native Guards militia was anything other than raised by its members. In any event, that is how militia units generally developed across the country – they were generally raised and paid for by its members.

Tom

The Regiment of Native Guards were a volunteer militia unit. The Native Guard were therefore State military, not Federal, and they never transferred to the CS army, so it’s doubtful the Confederate authorities took them into account at all until the siege of New Orleans in April 1862. They were not formed by the Confederate or the Louisiana Governments, they themselves offered their services to Governor Thomas Moore and were accepted, probably under the law creating a military board to get Louisiana on a proper war footing. I would take issue with the assertion that they were created as an act of Confederate propaganda. From everything I’ve been able to find, the offer to fight in April 1861 was a genuine one, motivated by a desire to protect their home from what they saw as an invading army.

They participated in more than two military reviews. In addition to the parades on November 23rd, 1861 and January 8, 1862, there was also in a parade observing the anniversary of Louisiana’s secession on January 27th, 1862 in which the Native Guard participated. In addition, there were other parades and activities that the 1st Division were a part of that the Native Guard, as a part of that division, took part in, such as funeral escorts for officers who had died in the field and were brought to New Orleans to be buried, an observation of George Washington’s birthday, and interestingly, an 1861 observation of July 4th Independence Day at Camp Lewis, where the 1st Division left New Orleans and joined the troops already in camp.

I’m also fairly sure they were not sent home by the February 15, 1862 militia law. That law disbands all state military so that they can immediately reorganize under new guidelines. I have orders and military notices for the Native Guards from February 15, 16, 20, 21, 27, 28 and March 15 that indicate they were active and under orders during the time that they were supposedly disbanded and sent home. The orders are in French, which may be why many have overlooked them. I think many of the Native Guard spoke French as their first language.

From the February 15, 1862 L’abeille de la Nouvelle-Orleans (New Orleans Bee) military notices, here is the original order to the Native Guards as printed in French, followed by a translation into English. The number and type of officers to be selected are exactly as specified in the revised militia law that supposedly disbanded the Native Guard:

– Nouve le-Orléans, 15 février 1862 – Ordre spécial No. 1 – confermément a l’ordennance du Quartier Général de l’Etat, les diverses compagnies se réuniront en bourgeoise a leur lieu ordinaire de rendez-vous, lundi soir à 6 heures, pour procéder a la réorganization des dites compagnies, et dilre pour chaque compagnie un capitaine, un premier, un second et un troisième lieutenant. Les capitaines nommeront immediatement apres (le meme soir) les sous officiers de leurs compagnies, [cinq sergents et quatre caporaux.]?

Les officers du Régiment se réuniront enmite [le meme soir] à la salle Economie pour procéder à l’election des officiers supériure (Field officers) du Rément.?

Par ordre du colonel F. Labatut.?

?

– New Orleans, February 15, 1862 – Special Order No. 1 – In accordance with the order of the State Headquarters, the various companies will assemble as burghers at their regular place of rendezvous, Monday evening at 6 o’clock, to proceed with the reorganization of the said companies, and will appoint for each company a captain, a first, a second and a third lieutenant. The captains will immediately thereafter (the same evening) appoint the non-commissioned officers of their companies, [five sergeants and four corporals].?

The officers of the Regiment will meet together [the same evening] in Economy Hall to proceed with the election of the Field officers of the Regiment.?

By order of Colonel F. Labatut.?

Nice information. Thanks for posting. Many militia units were created on the spot in 1861. Certainly in N.O. many literally sprouted like mushrooms. There was a large burst of patriotic fervor. The “enemy at the gates” was much on the their minds. It was then up to the CSA to decide who they would accept and when. I have been researching a few of them. The Sarsfield Rifles/Guards – they could not decide on which apparently – sprouted apparently from nothing in late 1860 and were very active through Spring, 1861. But, then they were subsumed into a completely different militia unit in Fall, 1861 and were deployed to western theater.

Tom

I think they genuinely formed to serve the State of Louisiana in 1861. I don’t think there is any doubt of that. And interestingly not all of that first militia went on, like Cailloux, to join and serve the Union.

As y’all probably know, at Port Hudson state park you can just about see where Cailloux was killed in the first assault at Port Hudson. It didn’t go well of course, and you can see that clearly because they never made it across Sandy Creek to even get near the earthworks. They got hammered.

Do you know Andre Cailloux’s profession as a slave that he was able to raise enough money to buy his freedom?

He was an apprentice cigar maker in a cigar factory I believe, and he learned to read while he was there.

Article: “[The Native Guard regiment] was momentarily reinstated when New Orleans panicked at the arrival of Union Flag Officer David Farragut and his flotilla. They were ordered to guard the east end of the French Quarter until Farragut’s imminent arrival prompted the evacuation of the city and its black militia.”

The city was under martial law. Only one person could have given that order. Who was it?

Nice article Sheritta! André Cailloux and his fellow Native Guards should forever be in our memory.

Time and again the same “Pious Causers” who tell us that the war was “about slavery,” and that the South seceded to “preserve and extend slavery,” are the same people who insist that there were no black soldiers in the Confederate military. To admit such would undermine their neatly packaged ideological narrative about the war. Yet the evidence is overwhelming that black men willingly served and bravely fought to defend THEIR southland.

A full year prior to Lincoln begrudgingly allowing blacks to serve in segregated Union Army units, the State of Tennessee passed legislation allowing blacks to serve integrated in its State units. What “Pious Causers” conveniently forget is that States Rights doctrine prevailed in the South; that prohibitions against blacks serving applied to the general government recruiting particularly slaves. The prohibition was a means of honoring property rights and State sovereignty, and slavery as an institution fell under the auspices of the reserved rights of the States.

In this article Sherrita Bitikofer asserts that the LA Guard “was intended to assuage Northern propaganda that claimed the Confederacy was racist and fighting for the preservation of slavery.” Do you suppose it was also a matter of the South being vastly outnumbered? And by the weight of sheer numbers, Southerners living cheek to jowl with blacks knew their capabilities to fight; unlike the North where its few black residence were ostracized and segregated. She conveniently omits that these LA blacks volunteered their services. On April 23, 1861, a public meeting was held in New Orleans, Louisiana to discuss Governor Thomas O. Moore’s call for volunteers to defend the South against the invading Union army as the War Between the States was just beginning. This particular meeting did not consist of white men, however. It was led and attended by what the newspapers called the “free colored residents;” Over 2,000 men attended. They declared “… the population to which we belong, as soon as a call is made to them by the Governor of this State, will be ready to take arms and form themselves into companies for the defence of their homes, together with the other inhabitants of this city….” 1,500 of the “flower of the free colored population” signed up to volunteer for Louisiana’s military. These men offered their services to the Governor and were accepted, an action which was widely covered and widely praised by the local press, and noted by some newspapers in the North as well.

I suppose the motive of Tennessee in passing legislation allowing blacks to serve integrated in its units, a full year prior to Lincoln begrudgingly allowing blacks to serve segregated in the Union Army, was to only to “assuage” Northern propaganda also? Here is the Tennessee law:

Tennessee State Law

Doc. 1861-033-02EX-00505;

Sec. 1. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the State of Tennessee, That from and after the passage of this act the Governor shall be, and he is hereby, authorized, at his discretion, to receive into the military service of the State all male fee persons of color between the ages of fifteen and fifty, or such numbers as may be necessary, who may be sound in mind and body, and capable of actual service.

2.That such free persons of color shall receive, each, eight dollars per month, as pay, and such persons shall be entitled to a yearly allowance each for clothing.

3. That in order to carry out the provisions of this act, it shall be the duty of the sheriffs of the several counties in this State to collect accurate information as to the number and condition, with the names of free persons of color, subject to the provisions of this act, and shall, as it is practicable, report the same in writing to the Governor.

4. That a failure of the sheriffs, or any or more of them, to perform the duties required, shall be deemed an offence, and on conviction thereof shall be punished as a misdemeanor.

5. That in the event a sufficient number of free persons of color to meet the wants of the State shall not tender their services, the Governor is empowered, through the sheriffs of the different counties, to press such persons until the requisite number is obtained.

6. That when any mess of volunteers shall keep a servant to wait on the members of the mess, each servant shall be allowed on ration.

This act to take effect from and after its passage.

W.C. Whitthorne,

Speaker of the House of Representatives

B.L. Stovall

Speaker of the Senate

Passed June 28, 1861

Note this law does not debar black soldiers the use of arms, which is another myth Bitikofer attempts to support by acting as though the LA Guard, not being supplied weapons, somehow means they were never really intended to be used as soldiers. What she does not mention is that given the shortage of arms in the South, the LA Guard members had purchased their own weapons.

She adds in this context “ The militia unit was disbanded on February 15, 1862,” failing to mention that the Governor ordered all militia units at that time disbanded in order to be reorganized under new State regulations. This was a military organizational revision, not a racial cleansing of the militia and volunteers. Governor Moore renewed the commissions of the Native Guards’ regimental field and staff officers as well as those of the officers of the Plauche Guards on February 15. Felix Labatut’s card states that he was “elected or appointed” Colonel of the Native Guards Regiment on February 15, 1862, the very date his command supposedly was “disbanded“ according to Bitikofer.

The South took the initiative in employing Negroes as soldiers; the South had the first black officers; the South even had the first black military chaplain; they were free Negroes, and many of them owned large interests in Louisiana and South Carolina. During the latter part of April, 1861, a Negro company at Nashville, Tennessee, offered its services to the Confederate Government. A recruiting-office was opened for free Negroes at Memphis, and the following notice was issued :

ATTENTION, VOLUNTEERS!

Resolved by the Committee of Safety, That C. Deloach, D. R. Cook, and William B. Greenlaw, be authorized to organize a volunteer company, composed of our patriotic free men of color, of the city of Memphis, for the service of our common defence. All who have not enrolled their names will call at the office of W.B. Greenlaw & Co. “F.W. Forsythe, Secretary. F. Titus, President…” p 83

These recruiting efforts were hardly meant to “assuage Northern propaganda.”

Bitikofer does all she can to give the impression that the LA Guard was mere window dressing for the South. Why then were they called up (though they never were really disbanded) to defend New Orleans from yankee invaders? I’ve seen records that indicate they did indeed fight in New Orleans. There is much Bitikofer omits to spin her desired impression of the Confederate Louisiana Guard. Including the fact that only 10% were willing to switch sides; who knows under what typical treats so common in USCT recruiting practices. For some writers, determined to paint the South as all bad, all the time, as long as the Native Guard come across as victims in their accounts, that’s all they are interested in. They have written something in conformity to the agenda.

They were definitely local militia, but they were never Confederate soldiers. If the Confederacy had intended free blacks or slaves to be soldiers, they would have conscripted them like everyone else, and they didn’t do that. Not until March of 1865, days before the capture of Richmond, did the Confederate Congress decide slaves could be conscripted into the ranks because there were no longer enough white men to conscript.