BookChat: The Atlanta Daily Intelligencer Covers the Civil War, by Stephen Davis and Bill Hendrick

I recently had the opportunity to do a BookChat with my ECW colleague Steve Davis about a co-edited volume he recently worked on with Bill Hendrick, The Atlanta Daily Intelligencer Covers the Civil War, published by the University of Tennessee Press. Today, I am pleased to offer Steve’s co-author, Bill, the chance to talk about the book, as well.

I recently had the opportunity to do a BookChat with my ECW colleague Steve Davis about a co-edited volume he recently worked on with Bill Hendrick, The Atlanta Daily Intelligencer Covers the Civil War, published by the University of Tennessee Press. Today, I am pleased to offer Steve’s co-author, Bill, the chance to talk about the book, as well.

Chris Mackowski: Where did you get the idea to write a book on how an Atlanta newspaper covered the Civil War?

Bill Hendrick: Steve and I are of two minds on this. Here’s my version. In the ‘90s I was a science reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. One day construction workers, while tearing down an old furniture company building, found evidence of the Atlanta that existed during the Civil War, and this was near my office. One of the artifacts found was a Hotchkiss shell fired by Sherman’s troops during the siege of Atlanta. I don’t remember who tipped me, but I rushed to the site and did a few stories on what was found. I have always been interested in archaeology.

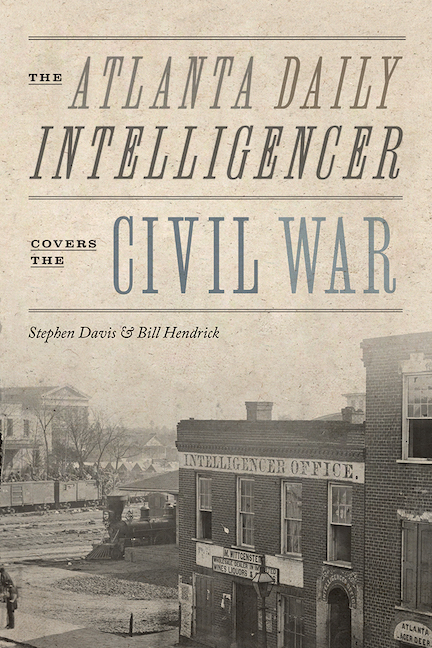

At the time the most important, even legendary historian in town was Franklin Garrett, then 87, of The Atlanta History Center. To my surprise, he agreed to walk around the muddy site with me‚in a suit and polished black wingtips—and pointed out, among other things, where the old Atlanta Daily Intelligencer building had once stood. I’d never heard of the paper or even thought about Civil War newspapers, but I wrote a few stories about the archaeological digs and got interested.

CM: So that’s where you got the idea for the book?

BH: Yes, the seed was planted, but all I did was procrastinate. For maybe 14 years. In 2008, with the newspaper industry dying, and looking for a future after a looming forced retirement, I checked with the Secretary of State’s office to see if the Intelligencer was still on the books. It wasn’t, so I registered the newspaper and starting paying annual fees, thinking I’d one day do a book or at least a website, but not having a clue where I’d get information on the Intelligencer.

CM: Is this where Steve Davis comes into the picture?

BH: Though I wrote business, health, science and feature stories, I really longed to dig more into history. So every time I found an excuse, I did stories on the Civil War, and Steve’s name came up as an expert on Atlanta in that period. So I started calling him and meeting him for various stories. He had the bonafides.

CM: And, I suspect, you had the time. You alluded a moment ago to a “force retirement”…

BH: Everybody has seen what’s happened to the newspaper industry. In late 2008, I accepted a buyout along with more than 100 other journalists, maybe 200. I was lost. Steve and I kept in touch, and in 2017, I think May, we met for lunch in east Cobb, where we both lived. It came up that I owned the Intelligencer name and his eyes flashed. “Let’s do a book on it,” he said, or something to that effect. I had no idea how to start a book project, but within two days Steve had written a proposal to the University of Tennessee Press. I’d still be procrastinating.

The proposal was quickly accepted—to my surprise, but not Steve’s. He has written at least eight books on the Civil War.

CM: How did the two of you get rolling from there?

BH: Steve mentioned he’d used microfilm in previous works, so I checked with The Atlanta History Center and they had almost a full run of four-page Intelligencer dailies on microfilm for the Civil War period, and even 20 or 30 real issues. At the Journal-Constitution, I’d always let the research department find historical documents on microfilm. So I had to learn how to use the microfilm machines and quickly saw it’d take forever to take notes while reading. Fortunately, the History Center’s microfilm readers had a device that allowed me to photograph the pages, and also to send those pages home, and to Steve, for more leisurely study.

CM: How long did that take?

BH: For more than six months I spent five or six hours a day at the History Center. We both started reading at our homes, making notes on what we found interesting, and then talked every afternoon at cocktail hour. It was a ritual. We got together to meet in person every week, or most every week.

CM: You and Steve have different backgrounds, so how did you decide what to include and how to proceed.

BH: Well, like most people, I knew a little about a lot of Civil War stuff, like what the major battles were, who won, who lost, but not details or much about politics. I minored in European history! Steve has a personal library of 3,400 Civil War books, and soon suggested we cover the war chronologically, page by page, which sounded OK to me. He did an outline.

Since I knew he was the military expert, I looked for stories and ads that would give us a glimpse of wartime Atlanta, the atmosphere, the psychology, current events, what it was like on the home front. Regular stories, like local crime, gossip on drunken citizens fined for obscene language, ads for patent medicines like one boasting it was a kind of 19th Century Viagra. And ads for slave auctions and slave markets and rewards for runaways.

Our goals meshed quite well. He knew what was important about battles, and I wanted to let today’s readers know what their ancestors were told, how they were propagandized, and how things worked, before the Internet or even good wire services.

CM: How did you two guys work together?

BH: Steve did much of the drafting, or more accurately, outlining of chapter sequence. Then we talked about what needed to be squeezed into those chapters, both in military and run-of-the mill news. We never mentioned who’d get the first byline, but I knew from the start he wanted it and in the end deserved it. Actually, I wanted the names to get equal play, somehow, like some of the Trump books, but I didn’t argue with what the UTenn designers came up with.

CM: What was your favorite part of the book?

BH: I noticed a short telegram, not an ad but just placed on a page like a news story. “Dear Father – I am at Jordan Springs Hospital near Winchester. I lost my left arm at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Come to me. Answer by telegraph.’’ As the father of two now middle-aged sons, that hit me like a gut punch. We don’t know why but the paper printed it, and apparently it reached a relative. There was no followup story as there would be today (or would have been in my day), but further research on the National Archives site and findagrave.com revealed that the young man, a lieutenant, was transferred to an Atlanta hospital and discharged before year’s end. He became a farmer and beekeeper in a suburb north of Atlanta. Then he moved a few miles east, fathered six children and lived to age 83. He’s buried in a well-kept cemetery in Cherokee County, maybe 20 miles from me.

CM: What other human interest stories jumped out at you?

BH: The Intelligencer ran a front-page story on May 22, 1863, about the execution of a private in the 46th Georgia named Jacob Adams. It was unusual in that this type of news rarely made the front page. And it was a story that would almost pass muster today. It was full of color and details about the execution. I think it was put on the front page to discourage soldiers from deserting, though that’s just my opinion. But it was also incomplete by today’s standards.

It’s doubtful the reporter for the Charleston Courier who wrote the story—picked up word for word by the Intelligencer—knew more than he wrote. Again, research using databases like newspapers.com revealed that the man was a serial deserter and a thug, having first deserted from the British army. In newspapers as far away as Scotland, we learned he’d been sentenced to death before, pardoned by Jefferson Davis, and had “several times attempted to murder people though heavily ironed.” The Courier reporter didn’t have access to the Internet, but we did.

CM: Why were such stories of interest to you?

BH: Because I was a reporter for nearly 45 years. I kept an “odd news’’ folder during the reading process, containing stories like one published on the front page of the New York Times but written by an Intelligencer reporter. The Times editors didn’t even bother to take out the Intelligencer reporter’s anti-Union editorial comments, such as asserting that “the enemy continues to perpetuate his practical jokes in the neighborhood of Atlanta’’ by shelling the city, and pointing out such was done endangering “a great many women and children…”

There were also stories about drunken men and women haunting Atlanta’s streets, men beating their wives (and being fined for it), still another bemoaning the apparent easy availability of liquor. There were stories about duels and warnings from officials to girls and women not to “flirt’’ with northern sympathizers.

CM: What did the Intelligencer have to say about slaves?

BH: That many ran away, and bounties were offered. Also that a major slave dealer was still thriving when Sherman was practically at the gates. One ad appeared regularly asserting that “Our stock of negroes is replenished every day” and that “no assortment south of Richmond is kept more complete.” Horrifying but every day stuff in the Intelligencer back then.

CM: I understand you worked for eight years for The Associated Press before going to work for the AJC? Was there an AP to distribute stories in the Civil War?

BH: Yes and no. In the North there was an organization called the New York Associated Press which sent stories from all over to paying subscribers, that is, most dailies and some weeklies. In the South this service stopped when the war began.

Efforts were made in the Confederacy, but they were less successful. Newspapers like the Intelligencer received news from reporters, soldiers’ letters home and citizens and others known to Intelligencer editors. But most southern newspapers also took part in an exchange system, which allowed them to print news from other papers word for word as long as credit was given. The farther away the exchanging paper, the longer it took for anything to be reprinted. For example, the Intelligencer ran a story on its front page on April 15, 1861, a story reprinted from the Mesilla Valley (Arizona) Times about a meeting of southern sympathizers there. This is the kind of story I looked hard for. Official dispatches from Richmond and various generals also filled white space. Much news was copied from the five Richmond dailies. And there was the telegraph, but it was expensive and budgets were tight.

CM: Were there any archival or family papers or other primary sources available on the Intelligencer or its editors or owners?

DH: Not that we could find, which was surprising because the Intelligencer was considered the city’s main paper, and editor John Steele and owner Jared Whitaker were prominent citizens. If papers exist, they’re in somebody’s attic and not at the National Archives, Library of Congress, or any of numerous historical societies I checked with.

CM: What got you interested in this topic in the first place?

BH: I was born and grew up in Virginia. I was told early, maybe 3rd grade, that my great-grandfather Hendrick “fought” in Lee’s army. (Turns out he did, and so did two other great grandfathers and one great-grandfather, all in the ANV.) I “wrote” an early paper complete with stick figure drawings in 2nd or 3rd grade on First Bull Run. I just copied from whatever cheap encyclopedias we had.

CM: Who, among your book’s cast of characters, did you come to appreciate better?

BH: John H. Steele, the editor. It’s amazing how much he wrote and pulled together with scant resources and no staff for a couple of years. But I really appreciated the work of the unnamed “compositors” who set type letter by letter and I think upside down. Isaac Pilgrim was described as “foreman” and stayed in Atlanta when the rest of the employees fled to Macon. He reported from Atlanta during the siege (which Steve calls a semi-siege).

CM: What’s a favorite sentence or passage you wrote?

BH: The anecdote about Lt. William Hoyle Nesbit, the guy who lost his left arm at Gettysburg. Not sure whether the version in the book was the way I wrote it or what Steve and I agreed to in one of our sessions.

CM: What modern location do you like to visit that is associated with events in the book?

BH: There’s very little in Atlanta that says “Civil War’’ because everything has been paved over in the name of progress. There is a tiny park near Collier Road just north of Atlanta where the Battle of Peachtree Creek took place—just a small patch of grass. But there’s very little unless you go way up to Kennesaw Mountain.

CM: What haven’t I asked you about the book that I should have?

BH: As a newspaper man who wrote tens of thousands of stories in my career, I wanted to see how the war was reported. I knew nothing about mid-19th century newspapers. Zero. Even typewriters hadn’t yet been invented. And frankly, I wanted to see if I could find one to frame. My office walls are plastered with framed front pages going back to a Harper’s Weekly that came out the week after Gettysburg, with a drawing of Meade on the cover. It’s a hobby. I saw an Intelligencer advertised for $800, but I was a newspaperman—we didn’t make the kinds of salaries that could let me pick it up!