“The thunder seemed tame:” Weather at the Battle of Gettysburg

Though soldiers’ letters and diaries often record observations on the weather, they usually speak in vague terms about rain or sunshine, cold or heat, and cloudy or clear skies. They don’t always include specifics about exact temperature, types of clouds, or wind speed and direction. As so many people are deeply interested in the details of such a significant battle as the battle of Gettysburg, it’s only natural that we are curious about the weather that the soldiers experienced. Luckily for us, the town was home to mathematics and natural sciences professor Michael Jacobs, who recorded the weather in July 1863.

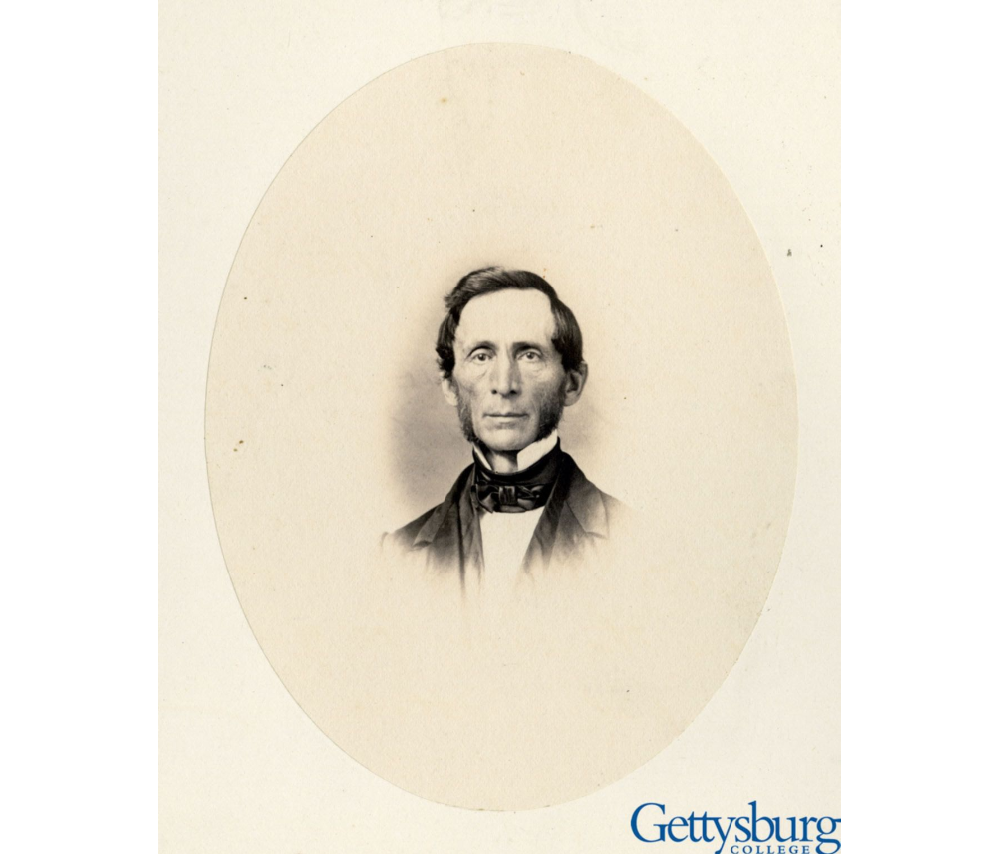

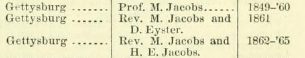

Jacobs worked at Pennsylvania College (now Gettysburg College), and had a strong interest in recording and studying weather. As early as 1849, Jacobs maintained a meteorological station for the Smithsonian Institution. When the armies came to Gettysburg, Jacobs understood the historic nature of the battle. During Pickett’s Charge on July 3, he called his son to watch from their roof, saying “Quick! Come! Come! You can see now what in your life you will never see again.” He later published Notes on the Rebel Invasion of Maryland and Pennsylvania and the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1st, 2nd and 3rd, 1863 (J.B. Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1864), one of the first books on the battle.

Perhaps most importantly, he didn’t let his town’s occupation by Confederates stop him from continuing to carefully record the weather. Adhering to the same Smithsonian standards as he had for many years, he meticulously noted the weather each day at 7AM, 2PM, and 9PM. In 1881, Jacobs’ son examined his father’s records and shared them, explaining that “they seem worthy of preservation, as affording data that should be considered in connection with the ever increasing attention given to the topography and incidents of those days.”

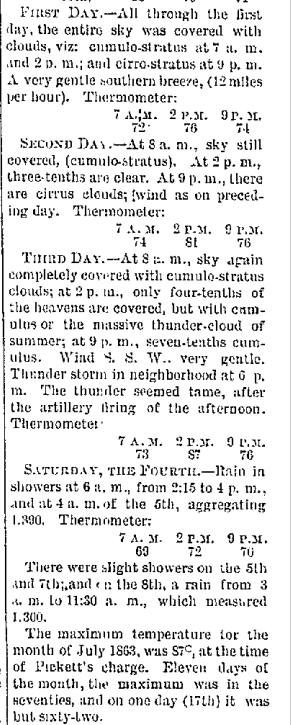

July 1: Cloudy, with a gentle southern breeze of 12 miles per hour. 72° at 7AM, 76° at 2PM, and 74° at 9PM.

July 2: The clouds cleared in the afternoon, and the wind was the same. 74° at 7AM, 81° at 2PM, and 76° at 9PM.

July 3: A storm rolled through, but “the thunder seemed tame, after the artillery firing of the afternoon.” 73° at 7AM, 87° at 2PM, and 76° at 9PM.

The hottest part of the battle coincided with Pickett’s Charge, and that was also the highest temperature for the month of July. Though Jacobs considered this apex of heat mild for the month, it is important to note that his recordings were likely taken in the shade. This means portions of the battlefield in direct heat could have been hotter.

After sharing his father’s notes, Henry Jacobs, who had watched Pickett’s Charge with his father, conjectured about the impact of weather on the battle. “The low temperature was undoubtedly a great blessing to the wounded, as well as to all in both armies… The frequent rains cleansed the fields of much that would have caused disease,” he wrote, but stated it was best left to other writers “to determine what effect the atmospheric conditions had upon the conflict, and to conjecture what result might have followed had we had that year an average July.” Even today, as we often tramp through Gettysburg of significantly hotter days than the soldiers experienced, we wonder about those same questions.

So on the 4th it looks like a cold front came through dumping 1.4″ of rain. How would that affect the decisions to move or remain in contact.

While there was some rain on the 4th, I don’t think it made a real impact on Meade’s choice to not attack that day or Lee’s decision to withdraw that night. Continued almost torrential rain in the days after the battle hindered the retreat, blocked river passage, and made soldiers miserable.

Last year The Battle of Gettysburg Podcast did an excellent episode on the weather and its impacts on the battle.

Actually, we have Michael Jacobs’ (my great great grandfather) weather observations for other days of the Gettysburg campaign. In the days leading up to the battle, it was cool with intermittent rain. The picture we usually hear of the troops marching in stifiling heat seems not to be the case during June and July of 1863.

I politely disagree. In a recent published book, The Weather Gods Curse the Gettysburg Campaign by Jon M. Nese and Jeffrey J. Harding is a standout contribution to the growing field of Civil War environmental history. Drawing on NOAA’s sophisticated re‑analysis models—paired with a rich array of soldier accounts—the authors reconstruct the day‑to‑day weather of the Gettysburg Campaign with a level of precision and clarity rarely attempted in Civil War scholarship.

The book’s most striking revelation is how severe the heat was in mid‑June 1863, a point that runs counter to the casual assumption that the campaign’s hardships began only with the fighting in early July. Nese and Harding show that a genuine heat wave gripped the mid‑Atlantic during the army’s northward march, with temperatures and humidity levels that pushed soldiers to the brink. Their modeling, supported by contemporary observers like Michael Jacobs of Pennsylvania College, demonstrates that the oppressive conditions were not anecdotal exaggerations but measurable meteorological events.

This heat mattered. It shaped marching speed, straggling, water scarcity, and the physical condition of the men who would soon fight at Gettysburg. The authors highlight cases such as Nathan Mullock Hallock rescuing a comrade from sunstroke—one of many reminders that weather acted as a “third combatant,” influencing the campaign as surely as Lee or Meade.

Structurally, the book proceeds day by day from June 3 to July 14, weaving together troop movements, weather reconstructions, and vivid firsthand accounts. Each chapter ends with a focused vignette that humanizes the science, grounding the meteorological data in lived experience. The maps—especially the color NOAA re‑analysis visuals—reinforce the argument, even if their placement in a central insert requires some page‑flipping.

Ultimately, Nese and Harding succeed in making complex atmospheric science accessible while deepening our understanding of the Gettysburg Campaign. Their work demonstrates that the story of Gettysburg cannot be told without acknowledging the punishing heat of mid‑June 1863, a factor that shaped the armies long before the first shots on July 1. The book is poised to become the definitive reference on Civil War weather for scholars and enthusiasts alike.

Thank You