Old and Timeworn: Sherman’s Armies Reach Fayetteville, North Carolina

On March 11, 1865 Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s army group entered Fayetteville, North Carolina. The evening before, Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee’s Corps had abandoned the city. Hardee left Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton’s cavalry behind as a rear guard. Lightly skirmishing with the lead elements of the Union column, Hampton’s troopers set fire to the Clarendon Bridge as they withdrew across the Cape Fear River. Sherman had hoped to use the bridge but now he would have to bring up his pontoon train. This was no bother as he intended to give his men a well-deserved rest.

Major Thomas Osborn, the Chief of Artillery for the Army of the Tennessee wrote in his diary that Fayetteville “contains perhaps three thousand people, is old and timeworn. It has probably been a fashionable town, but now looks old and rusty. A portion of the town is built on a series of little hills, perhaps one third of it on a plain. The country surrounding the town is as poor as the Lord could make it.”

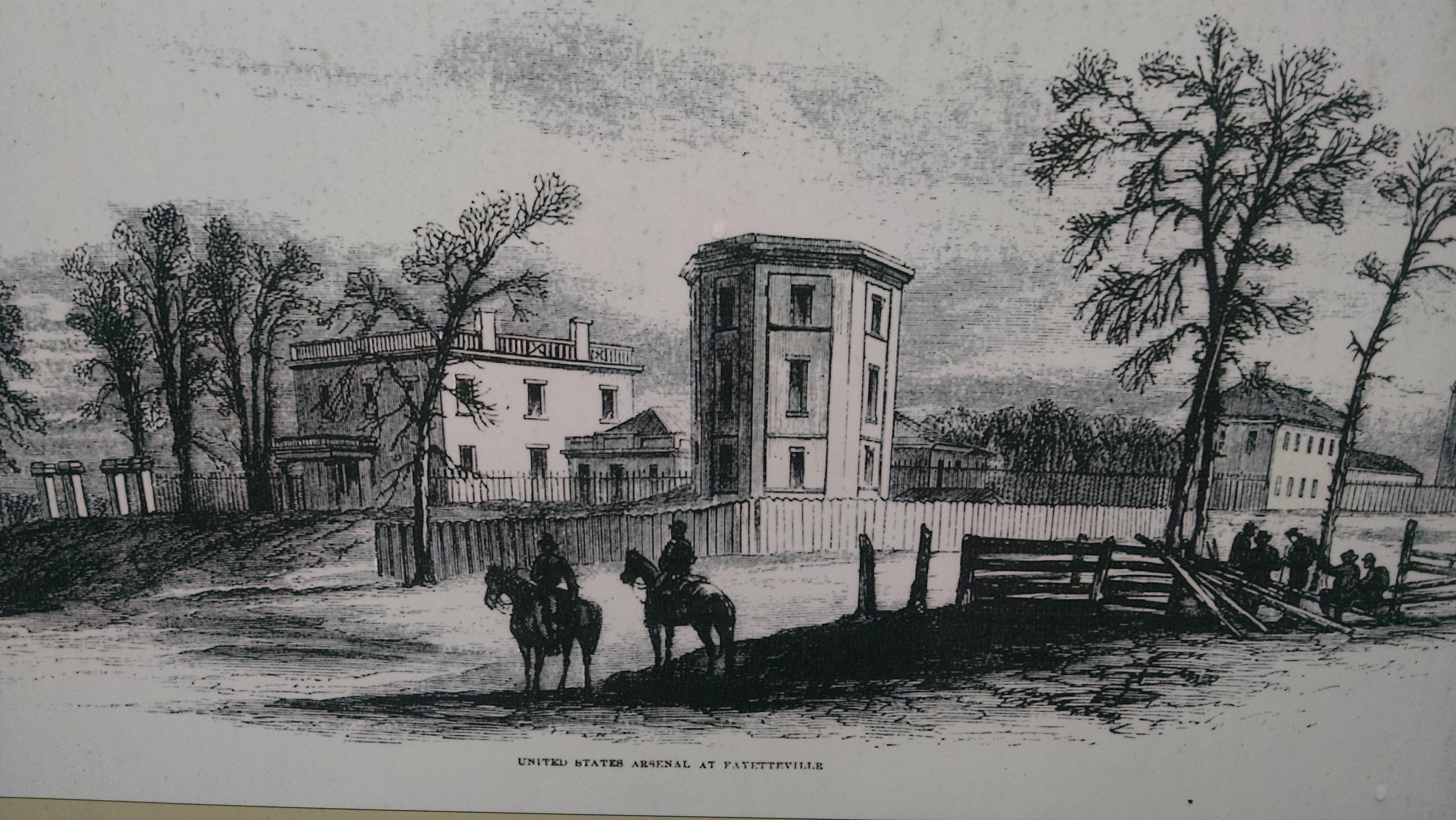

Sherman set up his headquarters on the grounds of the U.S. Arsenal. The following day, one of a “Sabbath stillness”, he wrote “shortly after noon was heard in the distance the shrill whistle of a steamboat…and soon a shout, long and continuous, was raised down by the river, which spread farther and farther…the effect was electric.”

The tug, Davidson, had arrived from the coast. It was the first time that the Federal armies had received news from the North since leaving Savannah. Over the course of the next few days additional boats would make the trip to Fayetteville, bringing with them coffee, hardtack, and new clothing and for the Union soldiers.

Theodore Upson of the 100th Indiana, along with some of his comrades had ventured into town to attend church when the Davidson arrived. Upson wrote “Captain Sherlock of Co. A got a N.Y. Tribune got up on a box and read it to the boys. The paper said Sherman and his Army were struggling through the swamps in the Carolinas and it was greatly feared that the Confederates would get together and do them up before they could get to coast. What a lot of faint hearts they must be down there in New York!”

While some of his men rested, others were hard at work. Under the direction of Sherman’s Chief Engineer, Col. Orlando Poe, the 1st Michigan Engineers and Mechanics drew the assignment of dismantling the old U.S. Arsenal. Seized in 1861, the Confederates transported machinery captured at Harper’s Ferry to the facility for the manufacturing of shoulder arms for the Southern armies.

Poe would later write “the Michigan Engineers were…set at work to batter down all masonry walls, and to break to pieces all machinery of whatever kind and to prepare the two large magazines for explosion. The immense machine-shops, foundries, timber-sheds, &c. were soon reduced to a heap of rubbish and at a concerted signal, fire was applied to these heaps, and to all wooden buildings and piles of lumber; also to the powder trains leading to the magazines. A couple of hours sufficed to reduce to ashes everything that would burn, and the high wind prevailing at the time scattered these ashes, so that only a few piles of broken bricks remained of that repossessed arsenal.”

After receiving a well-earned respite, the Federals resumed their march toward Goldsboro. The badly needed supplies lay only a few days’ march to the northeast. For many, the next several days would be the most harrowing of the campaign. On March 16, Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum’s Army of Georgia would engage Hardee outside Averasboro. Three days later, the largest Civil War battle fought in North Carolina would take place near the village of Bentonville.