What Did They Know?

Today, we are pleased to welcome back guest author Dwight Hughes

When considering historical events, it is too easy to wonder, given what happened, why in the world our ancestors did what they did. But we must remember that they did not know what happened. Their understanding of contemporary events would have been as confused, incomplete, fragmentary, and probably biased as ours is of current events, and I would not give much credit to modern technology for improving this situation. The following is a vivid illustration of that phenomenon. The CSS Shenandoah visited Melbourne, Australia in February 1865, and would go on to dramatically complete a destructive mission that no longer mattered. What did they know? It is true that these Southerners were as far away from domestic battlefields as it is possible to be, but consider also that the newspapers referenced were being read and believed by people at home.

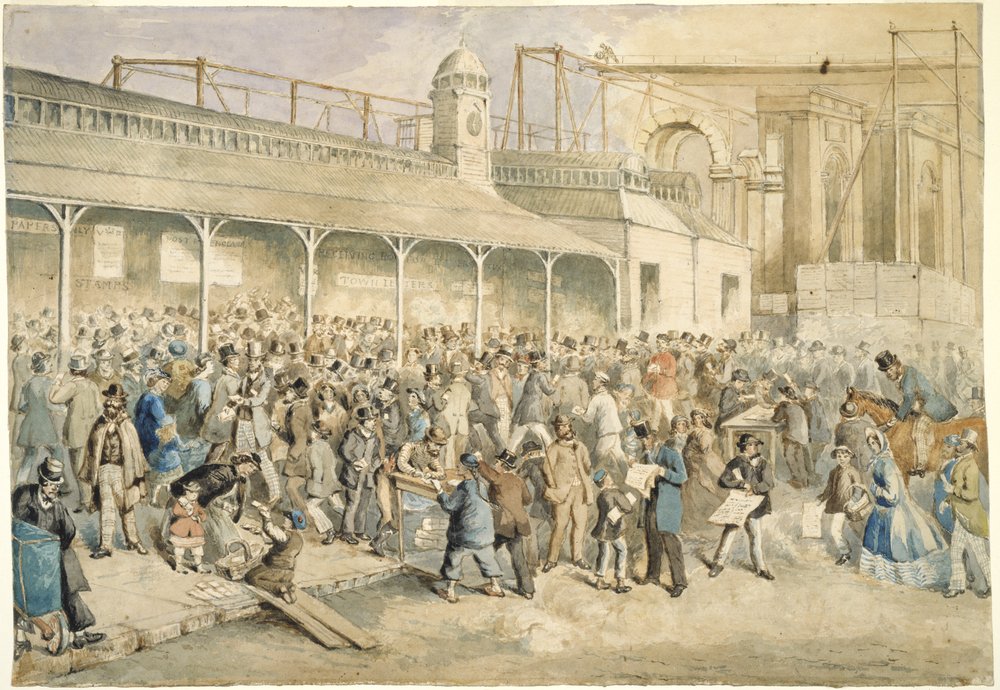

During the first two weeks in February, Melbourne papers reported war news dating from 18 November to 19 December 1864, eight to eleven weeks old. The ship Osprey crossed the Pacific with copies of the San Francisco Herald containing telegraphic bulletins and articles based on eastern editions; Albert Edward brought papers from Puget Sound. Other vessels carried information around Cape Horn or the Cape of Good Hope from New York and England, sometimes via Sydney.

Rumors and speculation jumbled with facts, then were repeated, excerpted, and summarized from the New York Times, Tribune, Herald, and Post, the New Orleans Times, and the Richmond Examiner and Whig among others. Some items were not attributed at all. It is difficult to distinguish truth in these reports from wishful thinking, misconceptions, and bias. “As usual, the operations of the armies have been attended with varying success and no decided results,” reported the Age. “The Federals, as usual, are reported to have sustained some reverses, but for the details we must await the arrival of the mail in the Bay.”[1]

Articles speculated where General Sherman was going after taking Atlanta and about Phil Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley; they discussed efforts of Confederate Generals Hood, Beauregard, and Early to stop them both. A dispatch from the Associated Press, dated New York, 18 November, reported that Richmond was full of rumors concerning Sherman’s movements, that he was meeting with great success, and that there was panic in gold. The New York Post‘s correspondent reported that the Richmond Whig stated that Sherman had sent a large part of his army towards Selma indicating a move on Mobile. The Whig also demanded that Confederate authorities call out a special force of seventy-five thousand men to annihilate Sherman and Sheridan, believing that could be done and assailing the congress for incompetency.

The New York Tribune‘s Army of the James correspondent wrote that Rebel papers expressed great anxiety at reported movements of Sherman’s army and the gravest apprehensions concerning powder mills, shops and arsenals at Augusta, Macon, and Columbus, Georgia. It was rumored that Robert E. Lee dispatched Generals Longstreet and Early with 35,000 men to intercept Sherman, which was not true. Jubal Early’s army was said to be in wretched condition and ready to abandon the lower Shenandoah Valley, which was true. It also was correctly reported that Grant was receiving reinforcements. He was reconnoitering the Confederates and massing on Lee’s right near Petersburg. “He is confident, and fully prepared.”[2]

The papers variously followed Sherman from Atlanta to the sea. “Confederate accounts…represent his march through Georgia to be marked by desolation.” Later unattributed reports had him investing Savannah but claimed that Union troops were short of provisions, and that Confederates were massing to oppose them with Beauregard, the hero of Fort Sumter, in command. Southerners concluded that the interior of Georgia had seen the last of invasion while their forces re-occupied Atlanta, and by quitting Georgia, the Federals so weakened their grasp of East Tennessee that they could lose the whole state. Most of this was wrong. Sherman had occupied Savannah on 22 December. As they were reading these reports in Melbourne, he was starting sixty thousand men north through the Carolinas on the final leg of his destructive campaign.[3]

Other false tidbits had Beauregard advancing on New Orleans instead of opposing Sherman in North Carolina. Sherman was expected to meet Georgia Governor Brown at Augusta to arrange for that state’s re-admission to the Union. Rebel General John Bell Hood reportedly advanced into middle Tennessee, cutting off all communication for Union-occupied Nashville. The city was short of supplies and Federals under General Thomas had been thoroughly defeated, losing five thousand prisoners and thirty guns. On the contrary, Hood had dashed his army to pieces against Thomas’s veterans at Franklin and Nashville (30 November to 16 December). The once proud Army of Tennessee fled into northern Mississippi and by February no longer existed as an effective fighting force.

There were rumors of a commission including George McClellan for the North and Vice President Alexander Stephens for the South to negotiate a peace; then it was said to have failed. Secretary of State Seward sent an apology to the authorities of Brazil for violating their neutrality during seizure of the CSS Florida and then insisted upon reparation or apology for firing on the United States flag. “If our cruisers were contravening her laws, she knew where to find us and how to adjudicate her claims, but the act of opening fire upon our vessels will be rebuked.”[4]

Confederate cruiser Tallahassee had been driven ashore near Wilmington, a total wreck, and Chickamauga was repairing at Bermuda after destroying “an immense quantity of shipping.” Actually, in a three week cruise out of Wilmington, Chickamauga captured only four ships, returned through the blockade, and was burned by the Confederates as the city was overrun.

The men of Shenandoah, expatriate Americans, and people of Melbourne on both sides of the issue read their prejudices into these reports. They could not know about the dramatic turnaround in the North since the fall of Atlanta from deepest despair to confident determination, or about the pending collapse of the Confederacy. No one in the antipodes could conclude that the war was almost over or who the victor would be.[5]

Three days after Shenandoah finally departed Melbourne, the Argus would reprint an undated article from an unnamed San Francisco paper noting that Shenandoah had been the common theme of conversation in that city and that the threat to commerce, “caused not a little uneasiness” among businessmen. However, continued the article, there were three Federal vessels on the coast. It was thought probable that Shenandoah would aim for Mexican or Central American waters, endeavoring to capture American treasure steamers and sailing vessels and then run into a South American port for coal and supplies.[6]

Captain James Waddell and his officers feared for their homeland but the situation would have seemed no worse than the sickening reversals of spring 1862, and not much different from the previous winter. The government controlled roughly the same expanse of territory: most of Tennessee, much of Louisiana, the banks of the Mississippi River from Memphis to Baton Rouge, and the Trans-Mississippi states. The U.S. Navy had taken Mobile Bay, but the city was safe. Georgia had witnessed the passage of a Union army, but was otherwise unoccupied. Aside from a few Union enclaves along the coast, North and South Carolina remained in Confederate hands.

As far as they knew, the Federals had not been able to take Savannah and Charleston, and blockade runners still ran into Wilmington with supplies from Europe. Other than Grant’s fifty-mile line holding Lee in front of Petersburg and Sheridan’s occupation of the lower Shenandoah Valley, Union forces controlled little of Virginia. An isolated and lonely group of Southerners in a faraway place clung to hope and duty. They were not inclined to a gloomy outlook that would render their dedication and sacrifice meaningless, and took what information they had as an incentive to greater effort in their country’s cause. Given this information, what would you think?

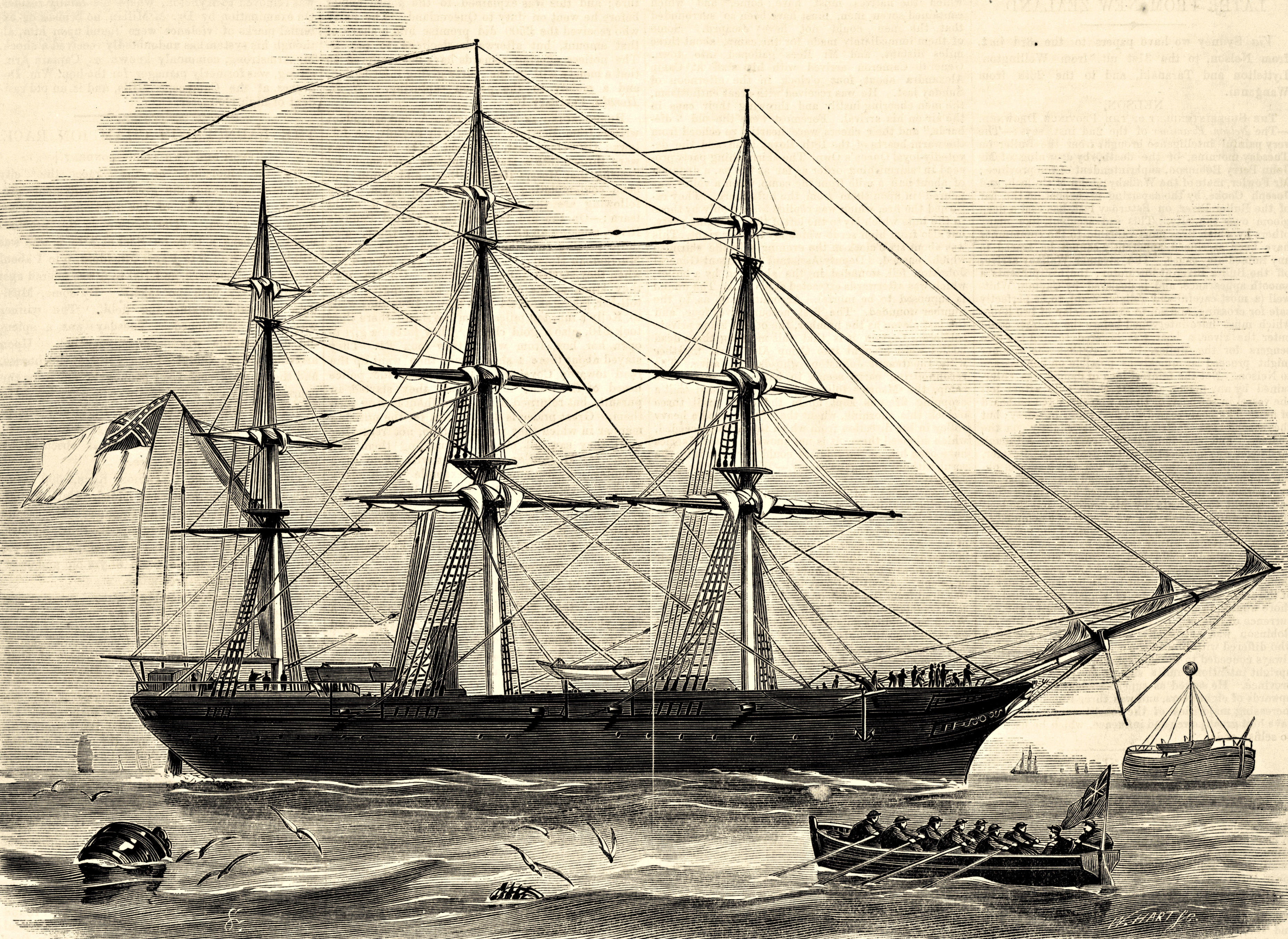

Picture captions:

- Shenandoah in Hobson’s Bay, Melbourne, February 1865. (State Library of Victoria, Melbourne)

- Mail Day: Arrival of the monthly mail steamer from London, c.a. 1865. (State Library of Victoria, Melbourne)

[1] Melbourne Age, 11 February 1865.

[2] Ibid., 6, 11 February 1865.

[3] Ibid., 13 February 1865.

[4] Ibid., 6 February 1865.

[5] Ibid., 11 February 1865.

[6] Melbourne Argus 20 February 1865.

As usual ECW copes another capable historian who brings and interesting point of view and writes well.