War’s End: Remembering a Cavalry Captain

Today, we are pleased to welcome guest author Sarah Kay Bierle

Your brother, Captain Hugh McGuire is wounded. The message branded itself into Dr. Hunter McGuire’s mind while dread twisted like a tourniquet around his heart. The situation he had feared since the beginning of the war became reality that April night in 1865. Raw aching pain of inability tore at the young doctor as he realized he couldn’t find his injured brother, couldn’t staunch the bleeding wound, and couldn’t know for certain Hugh was going to be alright. There was nothing to do except wait by that wretched, muddy road, held prisoner by night and disorganization while knowing that somewhere, a few miles back, his younger brother needed him. Momentarily haunted by the memories of other dying heroes who had dared to fight for a cause they supported, Dr. McGuire wondered with deep foreboding: would his brother perish and become yet another of the lost heroes of the South?

Somewhere in the darkness near Jetersville or Amelia Springs (Virginia), Hugh McGuire lay, suffering from a severe injury, needing a surgeon’s skill, a brother’s comforting hand, and a comrade’s reassuring word. This younger brother, overshadowed in the history books by his father and older brother’s accomplishment, was a hero to his men and his family. His leadership skills were remarkable, and his life story is as interesting and complex as his well-known brother’s.

Hugh (b. 1842) was the fifth child of Dr. Hugh and Mrs. Ann Eliza McGuire of Winchester, Virginia. He had three sisters and three brothers. His oldest brother was Dr. Hunter H. McGuire, medical director of the Confederate Second Corps and personal friend of General “Stonewall” Jackson. All the McGuire men served with the Confederate forces in the medical service, navy, spy agency, cavalry, or artillery. The McGuire ladies remained at home throughout the war years, enduring forty-eight occupations of their hometown by Yankees. The family home was used as Union officers’ quarters and, in the last year of the conflict, as a hospital.

Prior to the war, it seems that Hugh McGuire, Jr. was employed as a tutor in the area near Fredericksburg. He volunteered for the Confederacy with his older brothers in 1861 and eventually became a secretary for General Jackson. In the spring of 1863, Hugh transferred to the newly formed 11th Virginia Cavalry regiment and took command of Company E, holding the rank of captain.

The 11th Virginia Cavalry regiment participated at Chancellorsville, Brandy Station, Fairfield (Gettysburg Campaign), the Bristoe Campaign, the Overland Campaign, Petersburg, and in the Shenandoah Valley (1864). Hugh’s actions in battle are hard to trace and details are sketchy; at this time, research has only revealed clearly that he fought at the Battle of the Wilderness (May 1864) and the Appomattox Campaign (April 1865). While further research will shed better light on his specific actions in battle, the respect for Hugh McGuire from his men, peers, and commanders is without question. The historian of the Laurel Brigade wrote: “Being in the early flower of manhood, only twenty-three years of age, of splendid form, of genial and winning disposition, and rashly brave in battle, there were united in him the qualities that never fail to win the admiration and affection of men.”[i]

Hugh was described as handsome and “gallant.”[ii] The ideal of a Confederate cavalryman was personified in Captain McGuire, and it was not long before a romantic element was woven into his story. By the winter of 1864, his older brother Hunter accused him of feigning illness to spend additional time with a sweetheart. Details are shrouded in historical mists, but one fact stands clearly. Captain Hugh McGuire married Miss Sallie Gallaher of Waynesboro, Virginia, on January 12, 1865. Henry K. Douglas described the occasion and noted that Hugh’s bride was “fair and worthy of him… It was a merry, merry wedding [lasting] until after midnight.”[iii]

The newly-married couple only had a brief time together before Hugh returned to his company. The Gallaher home was raided by Yankees during March 1865 and the Battle of Waynesboro was fought nearby, but Sallie McGuire survived, watching and waiting for her husband’s return.

Petersburg fell on April 2, 1865, after a ten month siege. General Lee’s army moved west, hounded by General Grant’s forces. Union cavalry commanded by General Sheridan proved especially troublesome to the retreating Confederates.

Near Amelia Springs on April 5, 1865, the 11th Virginia Cavalry found itself in a fierce skirmish. In the words of the chronicler of the Laurel Brigade:

“The Federals in their retreat, when climbing the hill near Jeters house, were so closely pursued that they left the road and turned into the pines and escaped.

“The Confederates now halted and began to form, in anticipation of a hostile movement from Jetersville, for a large body of Federal cavalry was posted there. Soon from this direction a heavy column approached. The odds were great, but once more the grey troopers, McGuire’s company in front, dashed forward and turned back the Federal column, driving it pell-mell.

“The violence of the assault gave no opportunity to reform, and the superior numbers of the enemy only made the unwieldy mass an easier prey for slaughter. The Confederates rode among them sabering at will and chased the fugitives back into Jetersville.

“In this action the Federals lost heavily. The loss to the Confederates was small in numbers, but two of their best officers were mortally wounded, Capt. Hugh McGuire of Company E, Eleventh Virginia, and Capt. James Rutherford of General Dearing’s staff.”[iv]

Hugh McGuire was wounded in the left lung. Some accounts claim he was also taken prisoner. And thus, the unanswered questions begin. Where was he taken? Who cared for him? Lung wounds were serious, but statistically there was almost a 40% chance of survival. Hugh had much to live for. He fought against the tearing pain of each breath, fought against the fear, fought to live, to survive, to keep his dreams of the future.

Strong historical facts regarding Hugh’s life in these weeks are limited. From historical documentation, it is possible to conclude that Dr. Hunter McGuire found him and oversaw his transportation to Lexington, Waynesboro, or Winchester. Travel by horse-drawn ambulance would have been a painful trial, but perhaps the injury seemed to be healing.

Sallie McGuire joined her husband. (She spent the summer months of 1865 in Winchester, leading to the conclusion Hugh may have been moved there.) She was pregnant; she must have told Hugh. What did he feel? Hope for the future, another reason to fight to live, overwhelming love for his young wife, gloomy foreboding, and regret that he would not see their child?

According to his sister, Margaretta, Hugh realized he was dying, but responded with the bravery and nobility of character which had marked the rest of his life. He expressed peace, resignation, and a willingness to go. It was heartbreaking for Hugh’s family and wife to see his suffering and approaching death, but they tried to follow his example of faith and submission to a divine plan.

On May 8, 1865, Captain Hugh H. McGuire died. He is buried in Stonewall Confederate Cemetery in Winchester, Virginia. In a memorial published in a Virginia newspaper, the writer eulogized Hugh McGuire, saying:

“To the world, he has left the model of a patriot; to his country, he has left his services and life’s blood – a rich legacy to consecrate her cause; to his companions in arms, a shining example, which if followed, points, yet, the sure road to success and honor; to his friends, a thousand cherished memories to keep fresh the recollection of his virtues; and to his family and wife, an honorable name, and the consolations of that sublime faith which enabled him to triumph over the dangers that beset his path, and gathered round his death-bed.

“Friends mourn for him – the army lamented his loss, and Virginia, even in this hour of her agony, may well turn to drop a tear over the grave of a son so full of glorious promise, and so worthy of her fame.”[v]

The McGuire family mourned the loss of their husband, son, and brother. The war was over…but in the last days it had marred their dreams for the coming years. The depth of their grief is evident by an unwillingness to write about their loss. Dr. Hunter McGuire had great affection for his younger brother, and Hugh’s death must have prompted deep grief; he did not speak or write about his brother’s sacrifice in his published papers. It seems wrong to reconstruct the older sibling’s grief and feelings. It would be probing too deep into something he chose not to disclose. Unwillingness to write about a painful memory is understandable. Silence can sometimes be a road to healing. That must be respected and understood.

Yet, what about these untold stories? These forgotten heroes shrouded in the mists of time? It is the responsibility of historians to look deeper, to find these people unintentionally overshadowed by those who survived.

Captain Hugh McGuire was one of thousands of young men in the South who believed in something worth fighting for…worth dying for. What were those feelings which called so many men from the safety of their homes to the bloody battlefields? Over-simplified accounts claim they were defending slavery. Others cite states’ rights. One important thing to remember when entering this debate is that the politicians’ reasons for the war were often different than those of the common soldier.

If Hugh McGuire agreed with his older brother’s views, which were later written down, then he was not fighting to maintain slavery. He probably had a strong opinion on states’ rights, but the incident which drove him to enlist was the coming invasion of his home-state. That meant danger for his mother and sisters and danger to Constitutional liberties from his point of view. Captain McGuire – like many other young men – fought to defend his family and his home from invasion.

Today, there are many long-winded debates about the causes of the war and, indeed, there should be. Historians should seek to understand the causes of great events. But, looking back on this time through swirling opinions and a plethora of history books, do not become so embroiled in argument that the legacy of the young leaders of the South is forgotten. Politics can be disputed endlessly, but one thing which cannot be denied shines across the decades as a sterling example.

Like many other Southern men, Captain McGuire dared to stand and fight to protect his home, his mother and sisters, and his wife. He believed in honor, duty, faith, country, and family. He was willing to die to defend his values. And it was more than volunteering. He was willing to lead, no matter the cost, no matter how desperate the attack. Captain Hugh McGuire, “model of a patriot,” leaves a legacy and a challenge which echoes down through the years, reminding Americans to defend their values, families, and country.

[i] Captain William N. McDonald, A History of the Laurel Brigade, (1907), 373. https://archive.org/stream/historyoflaurelb00mcdo/historyoflaurelb00mcdo#page/n441/mode/1up

[ii] Reverend J. William Jones, Southern Historical Society Papers, Volume 22, (Richmond, 1894). http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0280%3Achapter%3D1.7%3Asection%3Dc.1.7.20%3Apage%3D45

[iii] Henry Kyd Douglas, I Rode With Stonewall: The War Experiences of the Youngest Member of Jackson’s Staff, (1968, University of North Carolina Press), 323-324.

[iv] Captain William N. McDonald, A History of the Laurel Brigade, (1907), 373.

https://archive.org/stream/historyoflaurelb00mcdo/historyoflaurelb00mcdo#page/n441/mode/1up

[v] Author Unknown, In Memoriam, (1865) Courtesy of The Library of Virginia

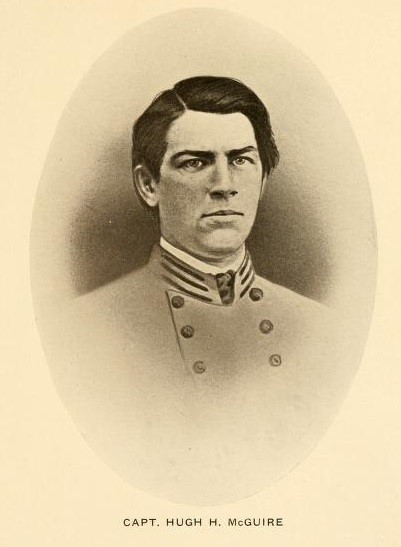

Photo of Captain Hugh H. McGuire from A History of the Laurel Brigade.

To the best of the author’s knowledge this photo is in Public Domain. https://archive.org/stream/historyoflaurelb00mcdo/historyoflaurelb00mcdo#page/n441/mode/1up

Photo of Confederate Cavalryman by Sarah Kay Bierle (Moorpark Civil War Re-enactment, 2014)

Photo of Confederate Cavalryman With Flag by Sarah Kay Bierle (Moorpark Civil War Re-enactment, 2014)

Sarah Kay Bierle, historian, living history enthusiast, and historical fiction writer, graduated from Thomas Edison State College with a BA in History. She enjoys extended research projects, especially ones focused on real people of the Civil War era. Sarah shares her love of history through living history presentations and her website (www.gazette665.com) She tries to keep the facts interesting and understandable, believing history should be informative and inspirational.

Beautiful writing and poignant, probing insights. I’ve long been fascinated by Dr. McGuire and am gratified to learn of his younger brother and family. Did Hugh’s child survive to adulthood? Did Sallie ever remarry?

With all due respect for Dr. McGuire’s reticence, which you sensitively acknowledge, thank you for bringing this story to light.

Hugh and Sallie McGuire’s baby was born on November 8, 1865; she survived to adulthood, married into a Mr. Cabell, had three children, and passed away on April 26, 1944.

I am not certain if Sallie McGuire remarried. I have not been able to find records or a tombstone for her, which leads me to believe she might have remarried and taken a different last name.

Thank you for your questions and your kind words regarding the article.

Correction: Mary McGuire (Hugh’s daughter) married Mr. Cabell.

Apologies for not mentioning her name and for the typo in my original reply.

Outstanding article, beautiful writing

Thanks, glad you enjoyed it.