Nobody Can Truly Understand The Battle of Gettysburg Without a Solid Understanding of the Battle of Chancellorsville

Conclusion

In the first part of this two-part series that demonstrates how nobody can truly understand the Battle of Gettysburg without having a solid understanding of the Battle of Chancellorsville, we addressed the implications of Chancellorsville for the Army of Northern Virginia. In this second part, we will examine the strategic implications of things that happened at Chancellorsville for the Army of the Potomac during the Battle of Gettysburg. By losing his nerve at Chancellorsville, Hooker did Lee a great favor and service by not standing in place and holding his line as his subordinates urged. Had Hooker done so, the Army of Northern Virginia would have suffered even greater losses dashing itself against the rocks of Hooker’s line at Chancellorsville. Those lighter losses made it possible for Lee’s army to invade Pennsylvania. But for Hooker losing his nerve, there would have been no invasion of Pennsylvania at all, and hundreds of books would never have been written about that one battle, including a bunch of mine.

Fighting Joe Hooker had two full infantry corps that were not heavily engaged at Chancellorsville. Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds’ I Corps was one, and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s V Corps was the other. Reynolds was very aggressive by nature, and it had to have driven him crazy to be held out of a large fight such as the one at Chancellorsville. Is it any wonder, therefore, that Reynolds pitched into the fray so eagerly at Gettysburg on July 1? His aggressiveness cost him his life that morning, but not before validating John Buford’s decision to stand and fight at Gettysburg.

It also bears noting that Reynolds was reportedly offered command of the Army of the Potomac in May 1863, after the Battle of Chancellorsville. Supposedly, Reynolds demurred because he would not be given a free hand and the ability to incorporate the Union garrisons at Harpers Ferry and Frederick, Maryland into the Army of the Potomac. It is, of course, pure speculation in trying to ascertain what sort of army commander Reynolds might have made, but we do know one thing: at Gettysburg, he lost his life as a result of being somewhere he had no business being. A wing commander such as Reynolds has no business placing individual regiments in line—that’s a brigade commander’s job—and Reynolds’ insistence in doing so exposed him to the bullet that claimed his life. This suggests that Reynolds might have micromanaged the army. But he made what was probably the single most important decision of the Battle of Gettysburg when he validated John Buford’s choice to hold and defend the high ground and ordered the I Corps to come up and deploy.

Similarly, George Meade’s V Corps also didn’t do much fighting at Chancellorsville after the first day. Meade’s advance had gained crucial high ground east of Chancellorsville on May 1. However, Hooker later withdrew from the commanding high ground—leaving it to Lee’s army—and instead took up a position on much lower ground at the Chancellorsville intersection. Ultimately, his army got clobbered after Hooker ceded the initiative to Lee. Again, is it any wonder that George Meade was so determined to hold the good high ground at Gettysburg?

Maj. Gen. O. O. Howard’s performance at Chancellorsville was atrocious. Howard, the commander of the XI Corps, ignored reports of a large enemy force operating on his flank and did nothing to prepare his men for an onslaught. Consequently, the XI Corps was overwhelmed and driven from the field. It never had a chance. Even though elements of the XI Corps stood and fought hard, its poor leadership set it up for failure and unfairly exposed it to becoming the laughingstock of the army. Incredibly, the same thing happened again at Gettysburg. Howard deployed two divisions of the XI Corps on an exposed plain sitting immediately below high ground held by Confederate artillery. There was a huge gap between the left of the XI line and Brig. Gen. John Robinson’s I Corps division on Oak Hill, and both flanks of the XI Corps position were in the air. When Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early’s Second Corps division crashed into the flank of the XI Corps at Barlow’s Knoll, it rolled up the XI Corps line and sent it flying in the face of an attack it never really had a chance to stop. The common fighting men of the XI Corps fought well in both instances, but became the scapegoats of the army because they happened to be the command that broke and ran on both occasions. Those men deserved better.

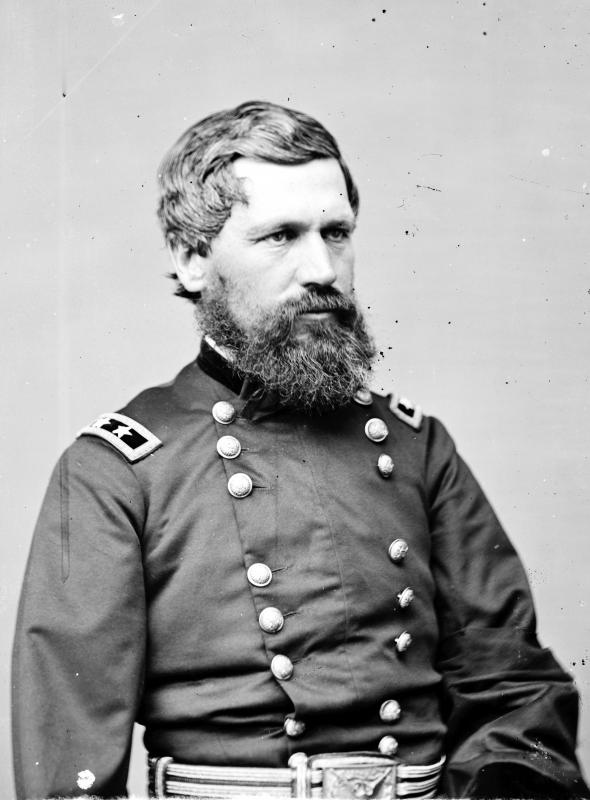

Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch, commander of the II Corps at Chancellorsville, was the senior subordinate officer in the Army of the Potomac. When Hooker was relieved of command of the Army of the Potomac at his own request on June 28, 1863, Couch would have been next in line for command of the army. However, Couch, who was utterly disgusted by Hooker’s terrible performance at Chancellorsville, refused to serve under Hooker’s command any longer, and requested a transfer. He was sent to assume command of the Department of the Susquehanna at Harrisburg. How Couch would have done in command of the army–instead of George Gordon Meade–is one of those daunting “what if’s” that we will never be able to answer. Couch’s transfer made it possible for Meade to end up in command of the army a scant three days before the beginning of the Battle of Gettysburg, and, fortunately for the Union, Meade was the right man in the right place at the right time.

Further, Couch’s request to be relieved from the Army of the Potomac made it possible for Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock to assume command of the II Corps, rather than commanding a division as he did at Chancellorsville. Hancock’s performance at Gettysburg was nothing short of magnificent on all three days of the battle. Had Couch not been transferred out of the Army of the Potomac, there was no guarantee that he would have been appointed to command the army. As such, he would have remained in command of II Corps, thereby blocking Hancock from playing such a critical role in the Union victory at Gettysburg.

Hooker sent his entire Cavalry Corps, save for one brigade, off on a terribly ill advised and extended raid behind enemy lines, thereby leaving his army blind and without any sort of an effective screen. That, in turn, meant that the Eleventh Corps flank was uncovered and in the air, setting it up to take the brunt of Jackson’s flank attack. Hooker then used the Cavalry Corps commander, Maj. Gen. George Stoneman, and its senior division commander, Brig. Gen. William W. Averell, as his scapegoats for the humiliating defeat that he suffered at Chancellorsville. Stoneman left the army on May 15 to seek treatment for a horrific case of hemorrhoids (as an aside, can one imagine how horrible hemorrhoids must be for someone who spent his days in the saddle? It’s no wonder that Stoneman was been described as crusty and dyspeptic) and never returned. He blamed Averell in particular for the fact that his command met heavy resistance at the beginning of his raid and turned back. He fired Averell and shipped him off to the backwater of West Virginia where Averell proved himself to be the most successful raider of the war.

Separate and apart from the strategic blunder of leaving his army without eyes and ears, Hooker’s choice of scapegoats had far-reaching implications for the mounted arm of the Army of the Potomac. Removing its two senior officers from the equation left Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton as the next ranking office in the Cavalry Corps. Pleasonton was a xenophobic toady, a schemer, prevaricator, and a lead from the rear sort of fellow. However, Pleasonton also had a keen eye for talent and he made the controversial choice to promote three young captains to brigadier general on June 28, 1863: George Armstrong Custer, Wesley Merritt, and Elon J. Farnsworth. Custer and Merritt both played major roles in the Union victory in the Civil War, and Farnsworth died a hero’s death at Gettysburg. Pleasonton’s assumption of corps commander also meant that his senior brigade commander, Brig. Gen. John Buford, became the commander of Pleasonton’s old division, the First Cavalry Division. Buford’s contributions to the Battle of Gettysburg are well-documented. But for the scapegoating of Stoneman and Averell by Hooker, Buford probably never would have had the opportunity to choose the battlefield at Gettysburg or to make the magnificent stand that he and his troopers made on July 1, 1863. Further, the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps might not have accomplished the feats that it achieved during the second half of 1863.

I’ve saved the most important implication for the Army of the Potomac’s performance at Gettysburg for last. Tammany Hall politician Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles commanded the Army of the Potomac’s III Corps at both Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. Sickles, an amateur soldier, was nothing if not aggressive. Early on the morning of May 3, Sickles was ordered to give up some very commanding high ground called Hazel Grove over his objections. Immediately after Sickles withdrew his men from Hazel Grove, more than 30 pieces of Confederate artillery occupied the plateau, and used it as a firing platform, pounding Sickles’ men from that high ground.

As a result, Sickles was determined not to give up high ground where Confederate artillery could then be employed to hammer his men again. At Gettysburg on July 2, Sickles was ordered to hold the southern end of the Union line. Portions of the Cemetery Ridge line were considerably lower than a plateau along the Emmitsburg Road near the Joseph Sherfy peach orchard. Determined not to find himself in another Hazel Grove situation, Sickles disobeyed orders and moved his entire corps forward to that high ground along the Emmitsburg Road, creating a large salient. When Longstreet’s sledgehammer attack came that afternoon before Meade could order Sickles to pull back, Sickles’ III Corps was nearly destroyed, and only a cannonball that took off Sickles’ leg prevented the general from being court-martialed by George Meade. There can be no doubt that the die for Sickles’ move forward at Gettysburg was cast at Chancellorsville, and that that move forward nearly cost the Army of the Potomac the opportunity to win the Battle of Gettysburg.

Once all of these factors are analyzed, it seems fairly obvious that one cannot truly understand the Battle of Gettysburg if one has a solid understanding of the Battle of Chancellorsville and its far-reaching consequences for both the Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Potomac. Hopefully, this brief discussion will help you to see this linkage and that it will encourage you to explore these parallels on your own.

Those are 2 outstanding posts, Eric – very good perspectives and connecting the dots. That was good reading

Thank you, Richard! I’m really glad to hear that you enjoyed them.

People forget that battles and decisions don’t occur in a vacuum – previous experience often plays an important role. These columns reinforce that idea well.

Thank you Eric. Good post. It shows you that the little things in war or life can change the outcome!!

Very well written!

I’m now reading Chancellorsville 1863, written by Ernest B. Furgurson a very will written book.