June 29-30, 1863

June 29 – 30, 1863

“My main point being to find and fight the enemy.” – George G. Meade

Twenty-four hours into his command, General Meade showed no signs of hesitation and continued to push his army hard to bridge the large geophysical gap that had developed between the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia during Hooker’s generalship.

The previous day, Meade’s orders had concentrated the army near Frederick, Maryland. Now, the orders for June 29 sent the army northward at a long and rapid pace. The left wing under Reynolds moved towards Emmitsburg, with only the Third Corps of the wing moving toward Taneytown. The distance of the left wing’s marches all exceeded twenty-five miles. The other columns of the army had marches that were all long, hot, and challenging as well on the 29th. Soldiers in the Twelfth Corps marched during the day until that arrived near Bruceville, Maryland, not far from Emmitsburg and Taneytown. To the south and east, the Second Corps, after a delayed start, spent the entire day on the road, arriving late into Uniontown. The Federal Fifth and Sixth Corps brought up the rear of the army. Although pushing throughout the day, the Fifth Corps ended their march south of Liberty, Maryland while the Sixth Corps finished their grueling day several miles to the north and east at New Windsor. General Meade also had the cavalry busy as well. General Buford’s troopers moved to the west and north in search of the Confederate First and Third Corps. General Gregg’s command headed north and east in search of the Confederate cavalry under General Stuart with additional orders to guard the flank of the Army of the Potomac. General Kilpatrick’s newly minted division was to head off in search of the Confederate Second Corps.

Both troopers in the saddle and infantry on the march remembered it as one of most trying days of their time in the Army of the Potomac.

At the close of June 29, Meade had not only moved his army northward, but he had secured both wings of the Army of the Potomac. He had chosen an excellent location for his headquarters in Middleburg, Maryland, which placed him effectively midway between the far flanks of the army. From Middleburg, Meade wrote General Halleck in Washington his proposed plans for the coming day. “My endeavor will be falling upon some portion of Lee’s army in detail,” Meade noted, with “My main point being to find and fight the enemy.” The commanding general was also well aware of Stuart’s ride and raid in his rear, but, in order to proceed with his plans for the army that he laid before Halleck and Lincoln, “I shall have to submit to the cavalry raid around me in some measure.”[i] At the same time, Meade also worked on ordering his commands to prepare for the advance on the coming day. Meade’s orders for June 30 would take into consideration all threats by the Confederate army and were in line with his directives from Lincoln and Halleck. Meade placed his commands in a way to be able to march towards or protect Harrisburg, Baltimore, or Washington. With this in mind, the order of march for June 30 inclined the army to the northeast towards York, Pennsylvania. In addition, the lengths of marches were to be cut significantly. Meade’s army was wearing under the long marches, number of hours on the road, heat, and dust. In order for the men to be in condition to fight well on the field of battle, Meade wanted to slow the pace of the campaign.

June 29 witnessed the first attempts by General Lee to concentrate his entire army since their entrance into Pennsylvania. According to Lee, “…on the night of the 28th, information was received from a scout that the Federal Army, having crossed the Potomac, was advancing northward, and that the head of the column had reached the South Mountain.” With this intelligence, Lee called off General Ewell’s approach and plans of the Pennsylvania state capital at Harrisburg and ordered him to “join the army at Cashtown or Gettysburg.” Lee also ordered his other two corps, Longstreet and Hill’s, to move towards the concentration point of the Cashtown-Gettysburg area as well. “Hill’s corps was accordingly ordered to move toward Cashtown on the 29th, and Longstreet to follow the next day,” recorded Lee in his January 1864 report of the campaign. As the main body of the Confederate army headed towards Chambersburg, Cashtown, and Gettysburg, General Stuart’s cavalry was on the move as well.

Stuart’s men continued their destruction of track and telegraph lines at Hood’s Mill. “The bridge at Sykesville was burned, and the track tore up at Hood’s Mills,” wrote Stuart. “Measures were taken to intercept trains…various telegraph lines were likewise cut, and communications of the enemy with Washington City thus cut off at every point.” Nearly all day Confederate cavalry occupied the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad with continued operations in this area. By the end of the day, however, Stuart’s men moved on Westminster, Maryland, but, so too had Union cavalry. Stuart had received intelligence that the Union army was concentrated around Frederick, Maryland, and, according to Stuart’s campaign report, “it was important for me to reach our column…to acquaint the commanding general with the nature of the enemy’s movements, as well as to place with his column my cavalry force.” In order to achieve this, Stuart’s troopers pushed on until reaching Westminster near 5:00 p.m. The column had had long rides. Stuart’s troopers riding from Brookeville had a twenty-five mile ride to reach Westminster, while those that left from Hood’s Mill had slightly less at seventeen miles. “At this place, our advance was obstinately disputed,” as elements of the 1st Delaware Cavalry under Major N.B. Knight engaged advance elements of the Confederate cavalry column at Westminster. A sharp but brisk fight took place down Main Street with the eventual scattering of the Union forces. Stuart and his men basked in the “Several flags and one piece of artillery” that were captured during and after the fight. After the brief encounter, Stuart sent out foraging parties, and, finding an abundance in the area, the men had for the first time in a week enough to eat. With stomachs full and mounts rested, the head of the cavalry column, Lee’s brigade, reached Union Mills, Maryland, half way between Littlestown, Pennsylvania and Westminster, Maryland following the skirmish. The night of June 29 saw Stuart’s column stretched out between the two points, and, at Union Mills, Stuart found a restful evening.[ii]

The following day, June 30, was to be a rather restful day for the Union army as well. Since Meade had taken command on June 28, the Union army had been in almost constant motion, seeking to bridge the gap between the two opposing armies that had opened during the previous weeks of the campaign under General Hooker. This constant marching had nearly depleted the ranks with thousands of stragglers falling by the wayside from heat exhaustion, sun stroke, and dehydration. In order to have his army in a better condition to fight, Meade’s men needed rest, shade, and water. Meade also realized that not only did his men need physical rest, but they needed to be in the mindset to be prepared to fight the enemy once again. To that effect, Meade issued a circular to be read to the troops by their respective commanders, “explaining to them briefly the immense issues involved in the [coming] struggle.” Meade wanted his officers to emphasize their men that “The enemy our on our soil. The whole country now looks anxiously to this army to deliver it from the presence of the foe.” The commanding general needed to make sure his men knew what was at stake, “Homes, firesides, and domestic altars are involved.”

At the same time, however, new and more accurate intelligence of Confederate dispositions in the operating area had arrived at headquarters, and with it, Meade needed to amend his orders of the previous evening. Meade had learned that Confederate forces were at Chambersburg and inclining a line of march east to Gettysburg while further enemy combatants were in Carlisle. These forces were to the north and west of the advancing columns of the Army of the Potomac while Meade had the army moving towards York. With this intelligence, Meade decided to strengthen the left wing of his army, the wing closest to contact with the Army of Northern Virginia. His movement of the Second and Third Corps on June 30 strengthened and supported the First and Eleventh nearby. The First Corps’ several divisions only moved between three and six miles coming to rest at Marsh Creek and Moritz Tavern for the rest of the day. The Eleventh Corps, another corps of the left wing under General Reynolds, moved through Emmitsburg and only a mile beyond to St. Joseph’s Academy. The last corps of the left wing, the Third Corps, spent most of the day watching as the Twelfth Corps marched past their camp at Taneytown. Finally in the afternoon they moved out towards Emmitsburg, a march of only eight miles. The Twelfth Corps was looking to get into Pennsylvania during their march and happily celebrated the feat near noon. One division spent the rest of the day camping at Littlestown, Pennsylvania while the Second Division, with reports of Confederate activity to the north and east of their position, aimed the direction of their march to Hanover, Pennsylvania. The final three corps, bringing up the rear of the army also moved little during the day. Although the Fifth and Sixth Corps marched on to Union Mills and Manchester respectively, the Second Corps rested in camp all day in Uniontown, Maryland.[iii]

Covering much more ground on June 30 than the Federal infantry was the Federal cavalry. General Kilpatrick’s division had spent the predawn hours of June 30 in Littlestown taking care of his men and mounts. Nearing dawn, this column of Federal cavalry moved out of Littlestown making their way towards Hanover, with their objective of York, Pennsylvania. As the lead elements of the division approached Hanover they collided with Col. Chambliss’ Brigade. Chambliss’ lead regiment “not only repulsed the enemy, but drove him pell-mell through the town with half his numbers, capturing his ambulances, and a large number of prisoners….” The Confederate cavalry were only initially successful. Further Union reinforcements arrived on the scene, counterattacked, and began the process of throwing up barricades in the streets. The defensive works acted as a force multiplier for the Federals as they awaited more supports. Not long into the break in the skirmish, Michigan troopers under the command of General Custer arrived. Dismounted, Custer’s men fought in a pitched back-and-forth action with Confederate cavalry as their slowly arriving reinforcements came to their beleaguered assistance. “After a fight of about two hours, in which the whole command at different times was engaged, I made a vigorous attack upon their center, forced them back…and finally succeeded in breaking center,” Kilpatrick reported to Pleasonton that evening. Only darkness brought an end to the fight, and with it, the retreat of the Confederate cavalry from the field.[iv]

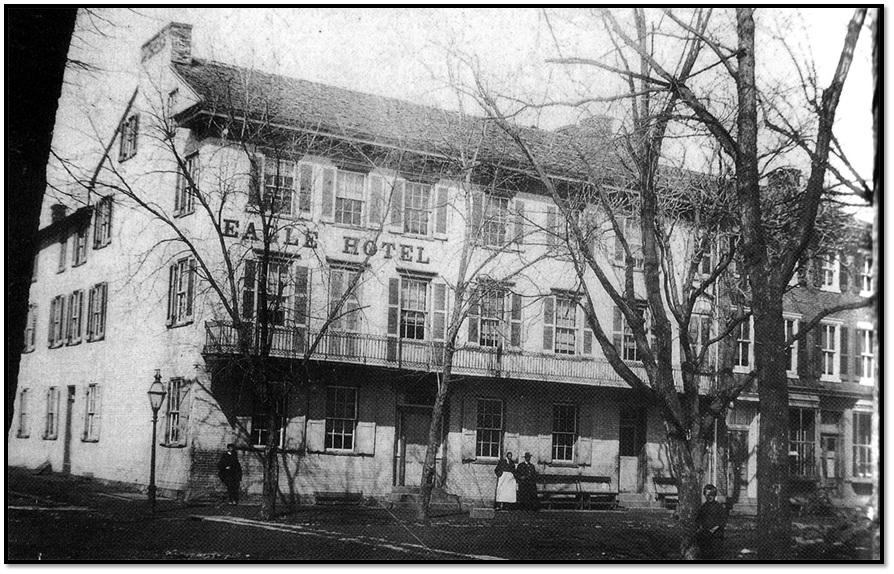

The other two divisions of the Federal cavalry corps also moved throughout June 30. General Gregg’s command had ridden throughout the darkness of June 29 and the early morning hours of June 30. With the dawn of June 30, Gregg’s troopers reached Westminster. After he heard of Stuart’s brief occupation of the town, Gregg was unsure if his intelligence that told him Stuart had left was reliable. Gregg entered into the town prepared to fight, and, once he discovered no sign of Confederate activity, issued orders for the command to remain in Westminster. Meanwhile, John Buford’s division of cavalry had reached Gettysburg. “I entered this place to-day at 11 a.m.,” Buford wrote to General Pleasonton. The arrival of his troopers met enthusiastic citizens of the town, happy to know that the Union army was there after their encounter with Early and Gordon’s commands days earlier. Buford at once issued orders for his men to establish vedette posts west, northwest, north, and northeast of Gettysburg. Their job was to screen the approaches to the town itself while also gathering as much intelligence on the location, size, and intentions of Confederate units operating in the area. As this was taking place, Buford established his headquarters

in the Eagle Hotel on the northwestern end of Gettysburg. He did not have to wait long to make contact with elements of the Confederate army.

“On the morning of June 30, I ordered Brigadier-General Pettigrew to take his brigade to Gettysburg, search the town for army supplies (shoes especially), and return the same day,” wrote General Heth.[v] And so one of the longest enduring myths and fallacy of the Gettysburg Campaign was born. Heth had ordered Pettigrew’s brigade to Gettysburg, but shoes would not be found. No shoe factory existed in the town of 2,400 citizens, nor had the town have much left to offer anyway. Illustrative of the problems of Confederate communications during the campaign and then tactically during the battle, Heth and his superior, General Hill, should have known that Early’s division, Gordon’s brigade, had already been through Gettysburg four days earlier and already acquired what little supplies had not been sent away by the townspeople. Heth had written his report of the battle two months after it had ended. Had his search for supplies as noted in his report provided cover for his brining on a general engagement on July 1 against the orders of Robert E. Lee? Regardless of this enduring myth, Confederate forces were on the march down the Chambersburg Pike towards Gettysburg on June 30. As Pettigrew’s command reached the north-south ridges west of Gettysburg he observed what he thought to be elements of the Army of the Potomac, particularly cavalry. By all information given to Pettigrew, the Federal army was miles away to the south and he should not encounter any resistance except militia or home guard units. “On reaching the suburbs of Gettysburg, General Pettigrew,” however, “found a large force of cavalry near the town, supported by an infantry force,” wrote Heth in his official report. What happened next was far different than the report itself.

Pettigrew knew not to bring on a fight, and despite his years of service in the Confederate army, he was relatively green to brigade and field command. Nevertheless, Pettigrew made an a great decision not to push the issue to gain entrance to Gettysburg, but rather return back to Cashtown. As Heth reported in September, “Under these circumstances, he did not deem it advisable to enter the town, and returned, as directed, to Cashtown.” When Pettigrew returned to Cashtown, he reported to his superior Heth, and Heth’s commanding officer, General Hill, that he believed that the force that blocked his way into Gettysburg was Federal cavalry from the Army of the Potomac. Both Heth and Hill on June 30 refused to believe Pettigrew’s observations. Hill had been with Robert E. Lee earlier and had seen where Lee believed that army to be, in the vicinity of Frederick, Maryland, certainly not Gettysburg. The young brigadier had merely seen home guard and militia. Because of Pettigrew’s failed mission, Heth asked permission of Hill to return to Gettysburg the following day, July 1, and accomplish what Pettigrew had not, a search of the town for supplies and shoes. Hill gave permission and a fateful decision that would influence the next three days in American history had been made.[vi]

Darkness on June 30 still found the Federal army busy, particularly the high command. A full day of activity by both armies lent Meade to issue orders that advanced the Union towards Gettysburg. Orders from Headquarters sent the Third Corps to Emmitsburg, the Second Corps to Taneytown, the Fifth Corps to Hanover, the Twelfth Corps to Two Taverns, the First Corps to Gettysburg, and the Eleventh Corps to Gettysburg, and the Sixth Corps to Manchester. In all, Meade had ordered two corps to or near Gettysburg with four other corps roads that all converged to the town itself. General Meade, although receiving constant updates from his commanders in the field and issuing orders for the army for the next, found time to write his wife. Two days into his role as commander of the Army of the Potomac, Meade told his wife that he felt he had already accomplished several objectives that Lincoln and Halleck had made priorities. “I think I have relieved Harrisburg and Philadelphia,” wrote Meade, “and that Lee has now come to the conclusion that he must attend to other matters.” Although he told Margaretta that “All is going on well,” he confessed that he was “much oppressed with a sense of responsibility and the magnitude of the great interests entrusted me.” “Of course,” Meade assured her, “in time I will become accustomed to this.”[vii]

The Confederate army continued to march to the concentration area of Cashtown and Gettysburg throughout June 30. Generals Anderson and Heth’s division were in Cashtown by the end of the day while the last division of General Hill’s Corps, General Pender’s, remained in camp at Fayetteville. The Second Corps under General Ewell moved much farther than the Third Corps on June 30. Still returning to the Confederate army from the western approaches of Harrisburg, General Johnson’s soldiers marched through Shippensburg and reached Scotland before coming to a halt to rest while General Rodes’ men halted for the night at Heidlersburg. Not far from Heidlersburg and Rodes’ column, General Early’s Division came to a halt on June 30 just three miles shy of that command. Ewell’s Corps had the lion’s share of the marching to reach the concentration point of the Army of Northern Virginia. Although often lost during campaign studies as these events hover so closely to the fighting of July 1, 1863, in just one day, Ewell had managed to pull two of his divisions together, a combined force of over 13,500 men. It was no easy feat. These two divisions, Rodes’ and Early’s, began their marches miles apart, were plagued by the heat and dusty roads, and lacked Confederate cavalry to screen their advance as most of Jenkins’ command lagged to the rear of the marching column.

Meanwhile, the First Corps, Longstreet’s Corps, was also on the move. At the end of a long, hot march, two divisions of the corps, Generals Hood and McLaws’, reached the foot of South Mountain after leaving Chambersburg early during the morning hours. The final division of the corps, General Pickett’s, remained in camp in Chambersburg during the day in order to cover the rear of Lee’s army that was concentrating further to the east.

As darkness consumed the landscape on June 30, 1863, the Confederate army, though well concentrated, still had large geographic spaces in which to cover to finish the concentration before risking combat with the Federal army. That evening, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had four of his nine infantry divisions east of South Mountain. Although more of the army was near at hand, there was a distinct disadvantage because of the terrain. A majority of Lee’s army was on the western side of South Mountain. If Lee needed to call upon more of his army the following day they would have to crowd onto a single road through the Cashtown Pass over steep inclines at a distance of ten miles. Would Lee need to do so? The answer to that question would have to wait until the following morning, July 1, when General Hill sent orders to have his men moving early and “discover what was in my front.”

Dan Welch

____________________

[i] OR, pt. 1, 66-67.

[ii] OR, pt. 2, 694-695.

[iii] OR, pt. 3, 415.

[iv] OR, pt. 2, 695. OR, pt. 1, 986-987.

[v] OR, pt.2, 637.

[vi] OR, pt. 2, 637.

[vii] Meade to his wife, June 30, 1863, in Meade, Life and Letters, II, 18.

1 Response to June 29-30, 1863