Grant, the Wilderness, and the Loneliness of Command

On the evening of May 6, 1864, Lieutenant General U.S. Grant considered the day’s events. The Battle of the Wilderness had just ended its second day, and Grant’s forces had been beaten and battered in a way he’d never seen. Both his flanks had been driven in, and panic had set in among some of the Army of the Potomac’s officers. The fate of the 1864 Overland Campaign hung on what Grant decided to do next.

That evening, Grant retired to his tent for what Bruce Catton called “an unpleasant ten or fifteen minutes.” Some of his staff heard him thrashing around. He was wrestling with the lonely weight of command, and staring into the abyss of failure.

It is almost a cliche to say “it is lonely at the top.” But there are times when a person is leading an organization or an enterprise (military or civilian) that everything rides on what he or she chooses to do in response to events not breaking favorably. Such times take the full measure of a leader, and their character, values, and vision. (I posted about such moments before here).

In his tent, General Grant underwent just such a test. It is impossible to know exactly what went through his mind in this most human and naked of moments, but others who have faced similar situations offer clues to his struggle.

On May 25, 1940, General the Viscount Gort stood before a map in his French headquarters trying to decide whether to use his last reserves to attack or shore up failing defenses as German troops hammered his men from three sides. He knew that 250,000 men of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), Britain’s only major field army, depended on him making the right decision.

Colonel Gerald Templer, one of Gort’s intelligence officers, saw him at the map and later described the scene: “I then walked in, to see Gort standing in a very typical attitude – with his legs apart and hands at his back. He was staring – quite alone – at a series of maps of Northern France and the Channel ports, pinned together and covering the wall of his small room . . . wrestling with his God and his duty at a moment of destiny. It was only later that I realized he was, at that precise point in time, taking the decision as to whether to bring the remains of the BEF out through Dunkirk . . . all my heart went out to him in his loneliness and tribulation.”

Gort’s example shows how his test looked from the outside. But the next example gets inside the commander’s head.

Gort’s example shows how his test looked from the outside. But the next example gets inside the commander’s head.

On March 5, 1944, Lieutenant General William Slim stood at an Indian airfield with a group of officers. Thousands of men and dozens of planes and gliders stood poised to launch Operation THURSDAY, the largest airborne attack of World War II to that point. Plans called for night landings on three drop zones deep inside northern Burma.

An hour before the planes were to take off, a jeep raced up and deposited an intelligence officer with new photos of the landing zones. One was blocked with logs, but the reason was unknown; the other zones were clear. Was this an ambush? Nobody was sure, and there was no time to investigate. Postponement was not an option; they had to go that night or cancel. “The decision is yours,” said Major General Orde Wingate, THURSDAY’s commander, to Slim.

“I knew it was,” recalled Slim a dozen years after. “Not for the first time I felt the weight of decision crushing in on me with an almost physical pressure. The gliders, if they were to take off that night, must do so within the hour. There was no time for prolonged inquiry or discussion. On my answer would depend not only the possibility of a disaster with wide implications on the whole Burma campaign and beyond, but the lives of these splendid men, tense and waiting around their aircraft. At that moment I would have given a great deal if Wingate or anybody else could have relieved me of the duty of decision. But that is a burden the commander himself must bear.”

Such moments as these become defining. Leaders need strong character, values, and vision to succeed; those without one or more of these attributes almost always fold under the pressure.

All three men above met the test. Grant came out of his tent and issued orders to prepare for a march to Spotsylvania. Gort decided to defend and march to Dunkirk and evacuation. Slim directed the operation to proceed under a modified plan, which proved successful.

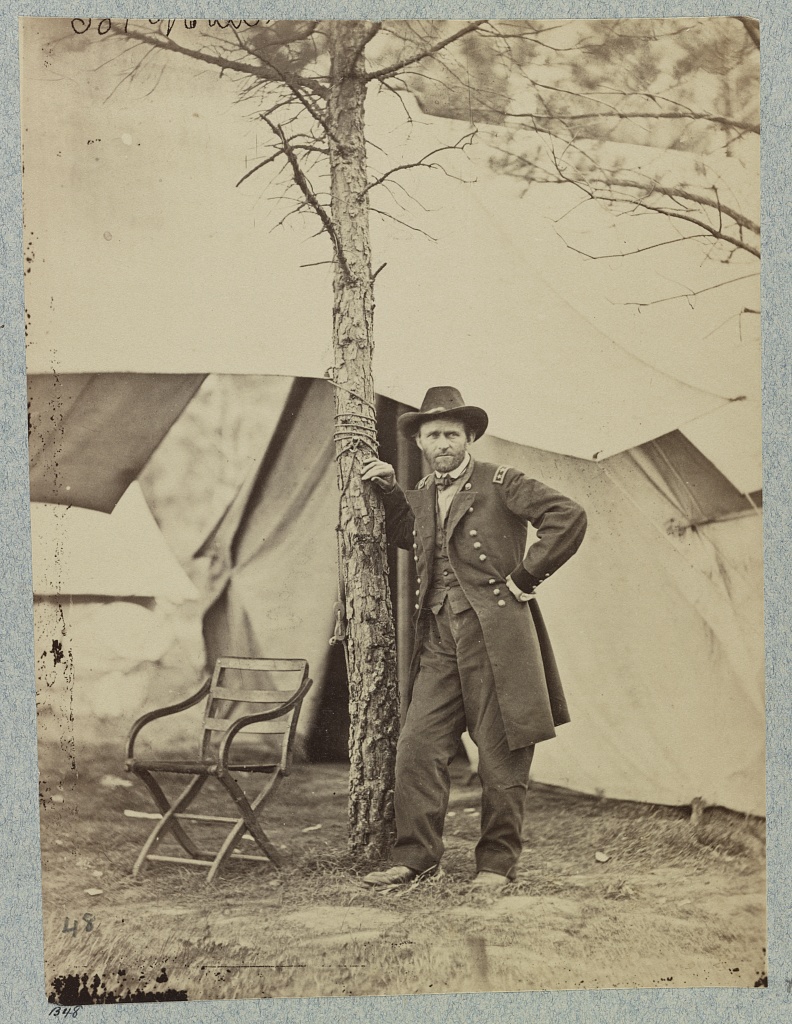

Top: General Grant in front of his headquarters tent, June 1864.

Middle: Viscount Gort in 1940.

Bottom: William Slim in London, 1945.

Reblogged this on seftonblog.

Don Spaulding in his print Loneliness of Command. points this out all to clear . My favorite print look it up .