A Monumental Discussion: Dana Shoaf

Before the tragedy in Charlottesville, Confederate monuments had already been sparking controversy around the country. Civil War Times, in an issue that now seems prescient, tackled the topic in its most recent issue, setting a high bar for rational, informed discussion. While talking with me about CWT’s project, editor Dana Shoaf offered to share his own thoughts on the controversy as part of Emerging Civil War’s series. We are privileged to have him join us.

Before the tragedy in Charlottesville, Confederate monuments had already been sparking controversy around the country. Civil War Times, in an issue that now seems prescient, tackled the topic in its most recent issue, setting a high bar for rational, informed discussion. While talking with me about CWT’s project, editor Dana Shoaf offered to share his own thoughts on the controversy as part of Emerging Civil War’s series. We are privileged to have him join us.

————

I inherited antiquarian tendencies. I’ve always wanted to surround myself with tangible, 3-D links to the past. I want to feel textures, and even breath deep the smells, of bygone eras if possible. That’s why I have a house full of 18th- and 19th-century material culture—most of it worth half of what I paid for it now that Mid-Century Modern antiques dominate the marketplace.

That’s why I liked viewing Confederate monuments. I was never fooled as to their meaning, at least not for the last 35 years after I began my serious study of the Civil War. I knew full well many were products of the Jim Crow era and were influenced by the Lost Cause tradition. I’ve never bought into the black Confederate soldier myth, and shook my head at the statuary that tries to reinforce it. But, I liked to look at those monuments artistically, to critique the uniforms and weaponry depicted on the statues, particularly those of individual soldiers in Southern town squares. And I liked to explain to the historical context of the statues to the people who were with me at the time.

Sound trite? Consider this.

Two years before he died, I took my dad to the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy annex of the Smithsonian Air and Space museum located in northern Virginia. We had a great day there. My dad, a World War II Air Corps vet and aviation buff, and I spent hours discussing the merits of numerous aircraft, including those bedecked with swastikas and rising sun emblems.

And every year, thousands of visitors of all nationalities enjoy that same antiquarianism without controversy because those planes of our former enemies are located in museums and very well contextualized. There is not, I realize, a precise parallel between World War II planes and Jim Crow-era statues, but the comparison does provide evidence that when placed in the proper context, controversial historical objects can be given new meaning and continue to help educate.

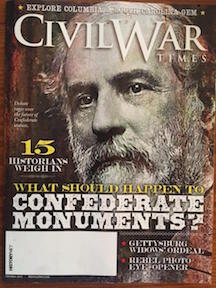

About a month ago, Civil War Times published an issue that contained the opinions of 15 historians and students of the Civil War regarding the monument controversy. In that issue, I stated in my editorial that the statues should not be removed, but placed in context with plaques, or perhaps the addition of other statuary.

Since then, the tragic violence of Charlottesville and the co-opting of Confederate monuments by neo-Nazis and white supremacists has forced me to modify my views on the matter. Whether I prefer Confederate statues to remain in place or not no longer matters. They have become flashpoints for modern hate and bigotry, and as Durham, N.C., proved, are in danger of destruction or vandalism if they remain in place.

Move them to a sculpture garden. Move them to a museum. Historian Steven Woodworth recently wrote an entry titled “The Right Way to Do It” at The Five Pilgrims blog of the success the University of Texas has had with moving a statue of Jefferson Davis into its Briscoe Center for American History. In that controlled environment, the statue benefits from contextual interpretation that allows it to function as an educational tool.

I’d like to close with a personal example of how a Confederate statue has helped me grow. Several years ago, I was discussing my attraction to the 1908 Confederate soldier monument in downtown Leesburg, Va., with a colleague. I was in full antiquarian mode, explaining how I appreciated the accurate details of the artwork, which stands on the grounds of the old courthouse, and particularly gushed over the fact the soldier “carries” an Austrian Lorenz musket, an imported weapon that was fairly common in the Confederacy.

The statue is posed with the musket held in a horizontal position, and after a moment of reflection, my friend said, “But imagine how you would feel if you were a black person in the 1920s, and had to pass under a statue of a white man with a lowered gun on your way to court?” I had never thought of that, I must admit, and have never looked at the Leesburg statue again without thinking of that statement. If that statue provided me with a “teachable moment” and helped me grow as a person and a scholar, it can help others do the same.

Thanks Dana for your straightforward examination of the monument issue. It was interesting to read that, like other writers contributing to this Monumental Discussion and like myself and (I assume) some other readers of this blog, your perspective on the way forward through the increasingly contentious debate about the monuments has evolved. I really appreciated the link you provided to Stephen Woodworth’s recent article about how the community at the University of Texas, Austin, constructively dealt with the bronze sculpture of Jefferson Davis that was on its mall and apparently resolved a divisive controversy. I hope others on this blog take the time to read it. I also really appreciated your bringing up the feelings and fears that African Americans who have to walk or drive past monuments to the defenders of slavery may experience. A few other of the contributors to the blog have brought this into the discussion, and its an important factor that, in my opinion, anyone considering the monuments ought to consider.

Thanks Dana for a well thought out viewpoint. One year ago I was 100% against removal. Through discussions such as this my views are evolving. I hope many monuments can remain for many of the reasons you eloquently stated. I also know some must inevitably come down. Your comments asking us to look at things from the viewpoint of African Americans is well put. I pray good discussion can continue and I especially hope that monuments at cemeteries and national parks will be safe. I fear they will not. And thanks to Emerging Civil War for providing this forum. Our politicians would be wise to join.

The answer to the Leesburg issue (and I speak as a many generation native of Leesburg) is to put up more monuments. A new one just went up for Rev War soldiers (shale we remove this because most of the Loudouners who fought in the Rev War supported slavery? But I digress…). Put up a monument to the enslaved, runaways or even the Quakers of Loudoun who assisted the enslaved. Add context, put more up and move forward

In Rome the statues of Caesar don’t have plaques stating he had Vercingetorix executed.

Be patient David, be patient.

“But imagine how you would feel if you were a black person in the 1920s, and had to pass under a statue of a white man with a lowered gun on your way to court?”

But this is not the 1920’s. America has elected an African-American to the highest office in the land – twice. We’ve had African-Americans on the Supreme Court, in presidential cabinets, etc, etc. Tearing down statues, monuments and renaming structures and streets does nothing for that person in the 1920’s. This is, in my mind, a perfect example of what Professor Gordon S. Wood wrote recently: “condemning the past for not being more like the present.” (See: http://www.weeklystandard.com/history-context/article/850083)

I would agree with Mr. Orrison’s position: add, don’t subtract.