Thinking About These Photographs

Compared to the number of Civil War photographs of soldiers, civilians, camps, and battlefields, posed photos of horses are rare. Clicking through Library of Congress’s online archives, though, I found some real photographic gems in this category.

Compared to the number of Civil War photographs of soldiers, civilians, camps, and battlefields, posed photos of horses are rare. Clicking through Library of Congress’s online archives, though, I found some real photographic gems in this category.

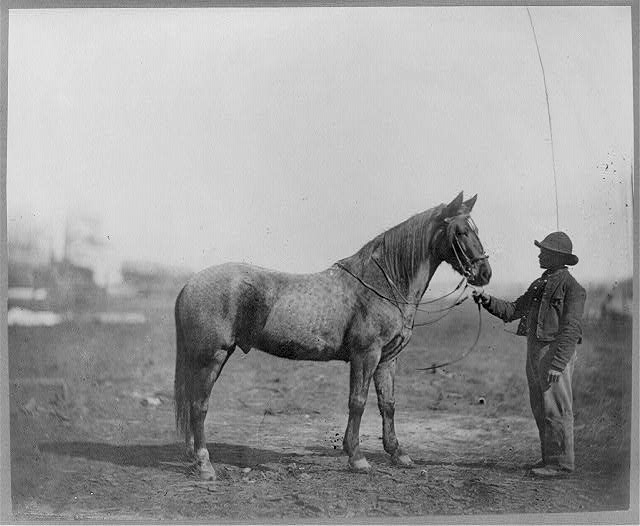

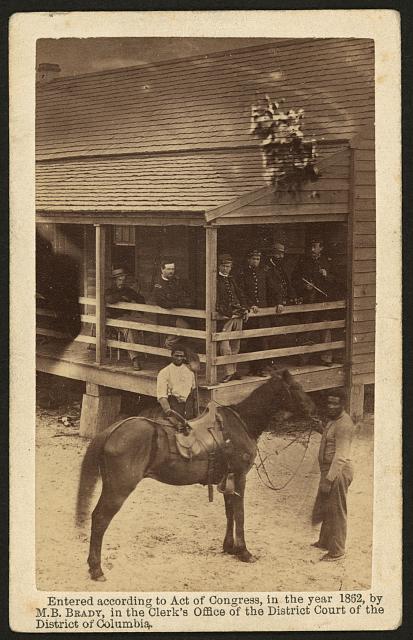

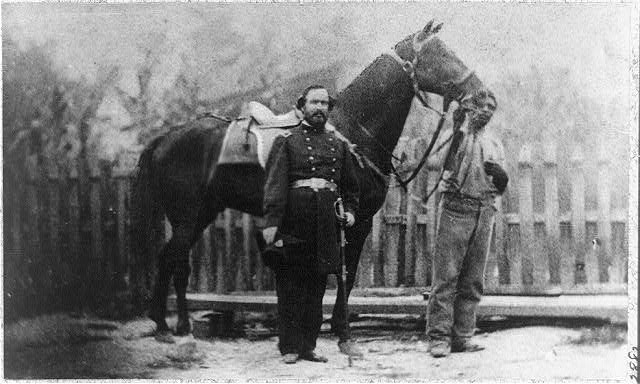

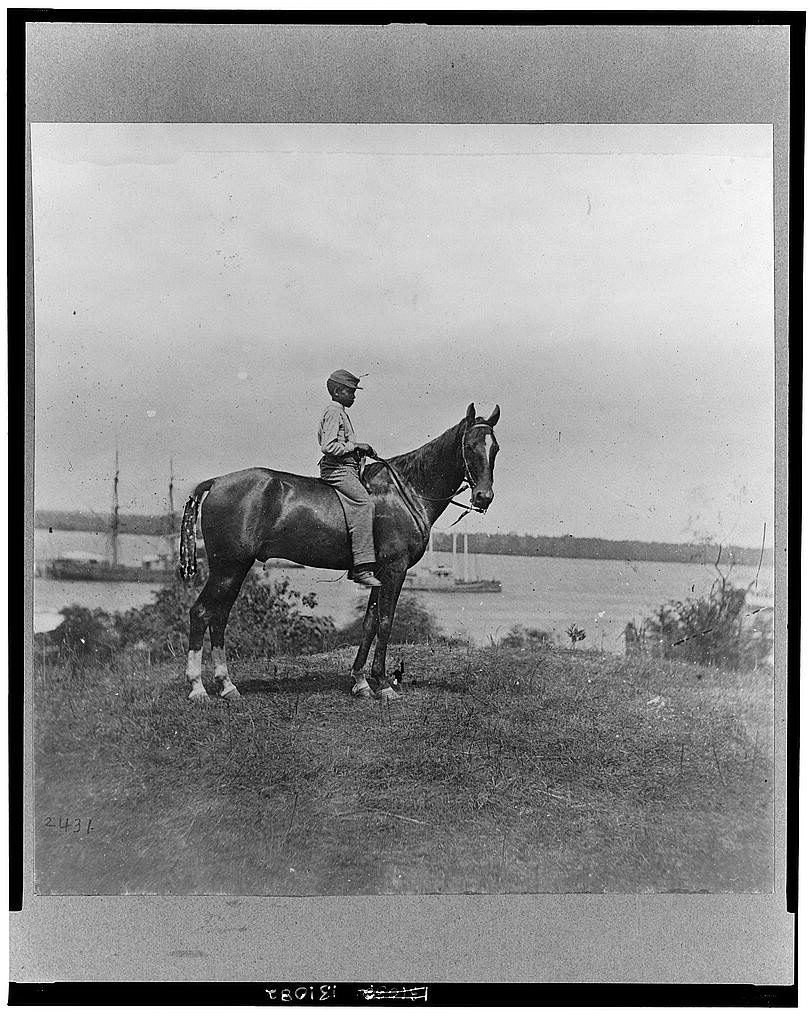

Looking closer at these photographs, I noticed some of them had one thing in common. In about half of the posed equestrian photos, a black man or boy controlled the horse or sat aside the animal. Honestly, I felt a little uncomfortable when I first made the observation. Was it a reminder of the racism and evolutionary comparisons plaguing the country that these men and boys were photographed with the animals?

However, as I continued thinking about this troubling subject I came to several conclusions as a researcher.

First, horses – particularly in the military setting prior to the mechanized age of war – were considered noble and magnificent animals. Warriors and generals liked to be depicted on war steeds in classic military art and photography. (Just look up some paintings of Napoleon or other famous commanders to see what I mean). These photographs are posed. These are magnificent animals on display for the camera, and in three of these four photos there isn’t a white officer in the foreground.

Which leads to the next points…

Second, these photographs show Union officers’ horses. Thus, it is a reasonable conclusion that the men and boys caring for these horses were freedmen, possibly even Contrabrand (escaped slaves who took refuge in Union lines) who were able to find steady work as horse grooms. On some of the Southern farms and plantations, some slaves were skilled horse trainers, talented riders, and careful horse grooms. It would be natural for an escaped slave who had equestrian experience with horses to seek a job looking after horses, and a Union officer might be pleased to hire someone to look after his animal(s). Still, it’s in only one photograph that I found that a Union officer decided to officially get in the photo with his horse and groom.

Third, as a historian I’m not blind to racist attitudes prevailing during the Civil War era. However, I think an argument can be made: why didn’t the Union officer have his hired man prepare the horse for portrait and then come take the reins for the grand photographic moment? Answers likely vary in each situation. However, drawing on the projected images of warriors on horseback, that type of posed photograph might have appealed to the officer. And yet – the groom or trainer – stands or rides in the photographs…

Fourth, there is nothing humiliating about the stances and poses of these freedmen. They stand proudly beside or in front of these horses, exerting a firm power over the animal. They aren’t crouching or tucked behind the animal. Likely, they groomed the animal for the photograph session. Animals – horses especially – often have a way of winning human friendship. Perhaps in a fast-changing and often cruel world, these horses were a steady friend and un-answering listener to these men and boys.

The young man who rides the horse takes a warrior’s stance. No, he doesn’t gesture grandly the way Napoleon does in the paintings. Rather, he is calmly in control, exerting his independence by working and managing the horse. In the photograph, this young man seems ready to take on the world and conquer his future.

Fifth, there is a strong possibility that these photographs of freedmen with the horses are the only images of these men. There is something wonderful about that. Their work was with the horses, and just like others, they were photographed proudly doing their jobs. At least we have photographs of these brave souls. If only we knew their names, where they were from, what struggles they had overcome, what challenges lay ahead of them… Some of the questions might be answerable with considerable research. Too often, the answers are forever lost, but at least we see their faces.

I don’t know what the photographer’s original thoughts or feelings were, but I know how I feel. Thinking it through, I’m glad we have these photographs. Without them, it would be easy to forget the incredible stories of freedmen and contraband who found work alongside the Union armies. Paid for their labor, these men cleaned, brushed, fed, watered, and saddled these horses. And one fine day they led the horse in front of the photographer’s camera. Perhaps they were surprised to be included in the image. Perhaps they expected a white officer to come and take the place of honor beside or astride the horse. Instead, they stayed and were photographed with the steeds, creating an image of men who worked hard and confidently hoped to take a traditional place of honor alongside the fabled military horses – ever ready to conquer life’s struggles and build a better world.

Here’s a consideration. Early cameras flashed and emitted smoke when they were operated. Early photographers could often be seen with black powder soot on their faces after taking pictures. I wonder if the black men seen in these photos might be the handlers of those horses, who could keep them calm as the cameras operated? That might not be the case in all of them, but might it be with at least some of them?

Beautiful, sensitive article. The more we know about war horses, the richer our lives are. Luckily they have pretty much disappeared from the battlefield, but certainly not from our imaginations or our hearts. Caring for them was a noble profession.

Sarah, just let me say how much I enjoy reading your post. I have thought about this for a bit and think that maybe it was as common to appreciate the man who groomed them as the horse its self. Sort of a status symbol, but not in a vain way (not too vain anyway) I don’t know, I like to belive that in these photos, that were intended to be sent to loved ones the passage would be something like’ I have enclosed within a likeness of my splinded horse Thunder and my man Bill, the one I wrote you about who takes such wonderful care of her’.That it was as naturel to them to have a photo of the horse and the man who took care of them,when in later years they wanted to rember a particular horse. Of corse I am not to sure of how much correspondence has been turned up with that sentiment, anyway, just my two cents.